Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page i • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

Government Misconduct and

Convicting the Innocent

Samuel R. Gross, Senior Editor, srgross@umich.edu

Maurice J. Possley, Senior Researcher

Kaitlin Jackson Roll, Research Scholar (2014-2016)

Klara Huber Stephens, Denise Foderaro Research Scholar (2016-2020)

NATIONAL REGISTRY OF EXONERATIONS

SEPTEMBER 1, 2020

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

National Registry of Exonerations

Newkirk Center for Science & Society • University of California Irvine • Irvine, California 92697

University of Michigan Law School • Michigan State University College of Law

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page ii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

For Denise Foderaro and Frank Quattrone

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page iii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

Preface

This is a report about the role of official misconduct in the conviction of innocent people. We

discuss cases that are listed in the National Registry of Exonerations, an ongoing online archive

that includes all known exonerations in the United States since 1989, 2,663 as of this writing.

This Report describes official misconduct in the first 2,400 exonerations in the Registry, those

posted by February 27, 2019.

In general, we classify a case as an “exoneration” if a person who was convicted of a crime is

officially and completely cleared based on new evidence of innocence. A more detailed definition

appears here.

The Report is limited to misconduct by government officials that contributed to the false

convictions of defendants who were later exonerated—misconduct that distorts the evidence

used to determine guilt or innocence. Concretely, that means misconduct that produces

unreliable, misleading or false evidence of guilt, or that conceals, distorts or undercuts true

evidence of innocence.

Three years ago, the Registry released a report on Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United

States. We found, among other patterns, that Black people who were convicted of murder were

about 50% more likely to be innocent than other convicted murderers, and that innocent Black

people were about 12 times more likely to be convicted of drug crimes than innocent white

people. Some of those disparities are caused by the type of misconduct we study here and some

are not.

Misconduct in obtaining and presenting evidence contributes substantially to the racial disparity

in murder exonerations, as we will see. On the other hand, the huge disparity in drug

exonerations primarily reflects a type of misconduct we don’t cover in this Report—racial

discrimination in choosing which people to stop or search for drugs, what is commonly called

“racial profiling.”

The Report describes many varieties of misconduct in investigations and prosecutions. Some are

always deliberate, some are rarely or never deliberate, and some may or may not be deliberate.

The Report organizes the myriad of types of misconduct into five general categories, roughly in

the chronological order of a criminal case, from initial investigation to conviction: Witness

Tampering; Misconduct in Interrogations of Suspects; Fabricating Evidence; Concealing

Exculpatory Evidence; Misconduct at Trial.

Most of the misconduct we discuss was committed by police officers and by prosecutors. We also

report misconduct by forensic analysts in a minority of cases, mostly rapes and sexual assaults,

and by child welfare workers in about a quarter of child sex abuse cases.

Some major patterns we observed:

• Official misconduct contributed to the false convictions of 54% of defendants who were

later exonerated. In general, the rate of misconduct is higher in more severe crimes.

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page iv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

• Concealing exculpatory evidence—the most common type of misconduct—occurred in

44% of exonerations.

• Black exonerees were slightly more likely than whites to have been victims of misconduct

(57% to 52%), but this gap is much larger among exonerations for murder (78% to

64%)—especially those with death sentences (87% to 68%)—and for drug crimes (47% to

22%).

• Police officers committed misconduct in 35% of cases. They were responsible for most of

the witness tampering, misconduct in interrogation, and fabricating evidence—and a

great deal of concealing exculpatory evidence and perjury at trial.

• Prosecutors committed misconduct in 30% of the cases. Prosecutors were responsible for

most of the concealing of exculpatory evidence and misconduct at trial, and a substantial

amount of witness tampering.

• In state court cases, prosecutors and police committed misconduct at about the same

rates, but in federal exonerations, prosecutors committed misconduct more than twice as

often as police. In federal exonerations for white-collar crimes, prosecutors committed

misconduct seven times as often as police.

We also examined disciplinary actions against officials who committed misconduct. These were

uncommon for all types of officials, and especially so for prosecutors.

We tried to determine whether official misconduct that contributes to false convictions has

become more or less frequent over the past 15 to 20 years. For most types of misconduct, we

won’t know for years to come, but we already see strong evidence that a few kinds of misconduct

have become less common: violence and other misconduct in interrogations; abusive

questioning of children in child sex abuse cases; and fraud in presenting forensic evidence. On

the other hand, the number of federal white-collar exonerations with misconduct by prosecutors

has been increasing.

In the last section we consider what led officials to commit misconduct. We conclude that the

main causes are pervasive practices that permit or reward bad behavior, lack of resources to

conduct high quality investigations and prosecutions, and ineffective leadership by those in

command. We discuss a range of possible remedies, from specific rules to changes in culture, in

cities, counties, states and the nation as a whole.

We present many other findings in the Report itself. The core of our data on official misconduct

are available online, sortable and filterable, for others to explore; go to the “OM Tags” column

here.

Samuel R. Gross

Maurice J. Possley

Kaitlin Jackson Roll

Klara Huber Stephens

September 1, 2020

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page v • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

Use Note:

1. Common terms

It may be useful to explain some terms that we use in this Report:

Exoneration means an exoneration listed in the Registry. Every exoneration,

identified by the name of the exoneree, has a page in the Registry, and is listed on our

Summary View and Detailed View pages.

Known exonerations: We know that our list of exonerations is incomplete: we

regularly discover cases we missed. Sometimes we specify that these are “known

exonerations,” more often we don’t, but it’s true regardless.

Misconduct in an exoneration: Strictly speaking, the practice we write about is

official misconduct that contributed to a criminal conviction that was ultimately

reversed by exoneration. That’s a mouthful. For convenience, we often refer to it as

“misconduct in the exoneration” even though the misconduct was part of the process of

obtaining a conviction.

Police: Police agencies in the United States range from one-person police departments

to the FBI. The titles of sworn peace officers include Patrolman, Officer, Deputy Sheriff,

Trooper, Agent—and many more. We refer to all of them as “police.”

2. Links and Navigation

(i) The report contains numerous links to pages on the website of the National Registry

of Exonerations. Most are links to the stories of individual exonerees; some are links to

collections of cases. In both situations, almost all links go to the current versions of the

pages, not those in effect in late February 2019, when we completed the set of 2,400

exonerations that are the subject of this report. For example:

• This link goes to Ricky Jackson’s page, which was last updated in May 2020. That

page contains information we did not know when we completed the compilation

of the dataset fifteen months earlier—and (like other summaries and data on the

Registry) it may be further modified in the future.

• This link goes to a list of all exonerations with misconduct in Cook County at the

time you click on it—230 as of this writing, more in months and years to come—

not the 204 exonerations with official misconduct in Cook County among the

2,400 exonerations included in this Report.

(For technical reasons, a few links go to copies of Registry pages rather than live pages.)

(ii) The Executive Summary and the Table of Contents contain links that may help

navigate this document. The Summary contains a list of page numbers in the form of

links—like this, 9—that take you to the indicated page in the text. In the Table of

Contents you can click on any part of an entry to go to the page on which that section

begins.

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page vi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

(iii) Each page of the text (except the first pages of major sections) includes two

highlighted buttons:

Go to Executive Summary and Go to Table of Contents.

If you click on them, they will take you to the beginning of the Executive Summary and of

the Table of Contents, respectively.

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page vii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

Acknowledgements

We didn’t do this on our own. Not nearly. It took a couple of villages and a lot of friends.

This report was produced by the National Registry of Exonerations. The editors of the Registry

were essential: Barbara O’Brien, Editor in Chief; Simon Cole, Associate Editor and Director; and

Catherine Grosso, Managing Editor. They read drafts, classified cases and thought through the

project with us. The Registry staff—Ken Otterbourg, Jessica Weinstock Paredes, Meghan

Cousino, and Eva Nagao who left us this June—were equally essential. They identify the cases on

which our work is based; research, code and write them up; and maintain the website through

which the work of the Registry is available to the world. We also received invaluable support and

advice from our Advisory Board, especially Denise Foderaro, Barry Scheck, and Rob Warden,

co-founder of the Registry.

The core work of our work—researching, coding, checking and recoding information on official

misconduct in the 2,400 cases in our database—was mostly done by a dedicated group of

research assistants—some of whom also did legal research, wrote memoranda, commented on

and corrected partial drafts, and provided advice at many stages. Most were students at the

University of Michigan Law School—Christine Adams, Zachary Adorno, Claudia Arno, Jennifer

Chun, Michael Darling, Lauren Flamang, Max Greenwald, Griffin Hardy, Caroline Howe,

Connor Lang, Ginny Lee, James Millikan, Amanda Rauh-Bieri, Amanda Stephens, Jenny Stone,

Julia Xin and Eric Yff—or at the Michigan State University College of Law: Nadine Kassem and

Alison Swain. In addition, we received excellent contributions from two young lawyers, Marc

Allen and Eli Wykell, and careful statistical analyses from Josue Guevara, starting when he was

a student at Michigan, German Marquez Alcala, who works for the University of Michigan Law

Library, and Valerie King, as graduate student at the Univesity of California, Irvine, and after

she completed her degree.

The staff at the University of Michigan Law School was as skillful and helpful as always. In

particular, Cheri Fidh corrected more errors in content and format than we can count, while

Alex Lee and Richard Savitski are responsible, respectively, for the appearance and the contents

of the data we are making available online with this report. At a distance, Julie Smith designed

the appearance of the report, and Margot Friedman worked tirelessly to present it to the world.

The staff of the Innocence Project was unfailingly helpful, including especially Barry Scheck and

Rebecca Brown, who answered questions, provided information, read drafts, and suggested

additions. Elizabeth Webster, formerly of the Innocence Project, spent a summer helping us

devise our initial coding system. And our dear friends in Ann Arbor, Phoebe Ellsworth and

Alexandra Gross, read partial and full drafts of this report repeatedly over several years, made

countless corrections and suggestions, and sustained our spirits.

The Registry, and this project in particular, depend on generous financial support from many

individuals and organizations. We are particularly grateful to James and Martha Newkirk, and

to Denise Foderaro and Frank Quattrone, who encouraged and supported our work since its

inception, in many ways.

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page viii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

The Registry is a joint project of three universities. We are fortunate to have had the support of

the University of Michigan Law School, our original home for several years; the Michigan State

University College of Law, which took us on four years ago; and the Newkirk Center for Science

& Society at the School of Social Ecology of the University of California, Irvine, which has been

our main home since 2016.

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page ix • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

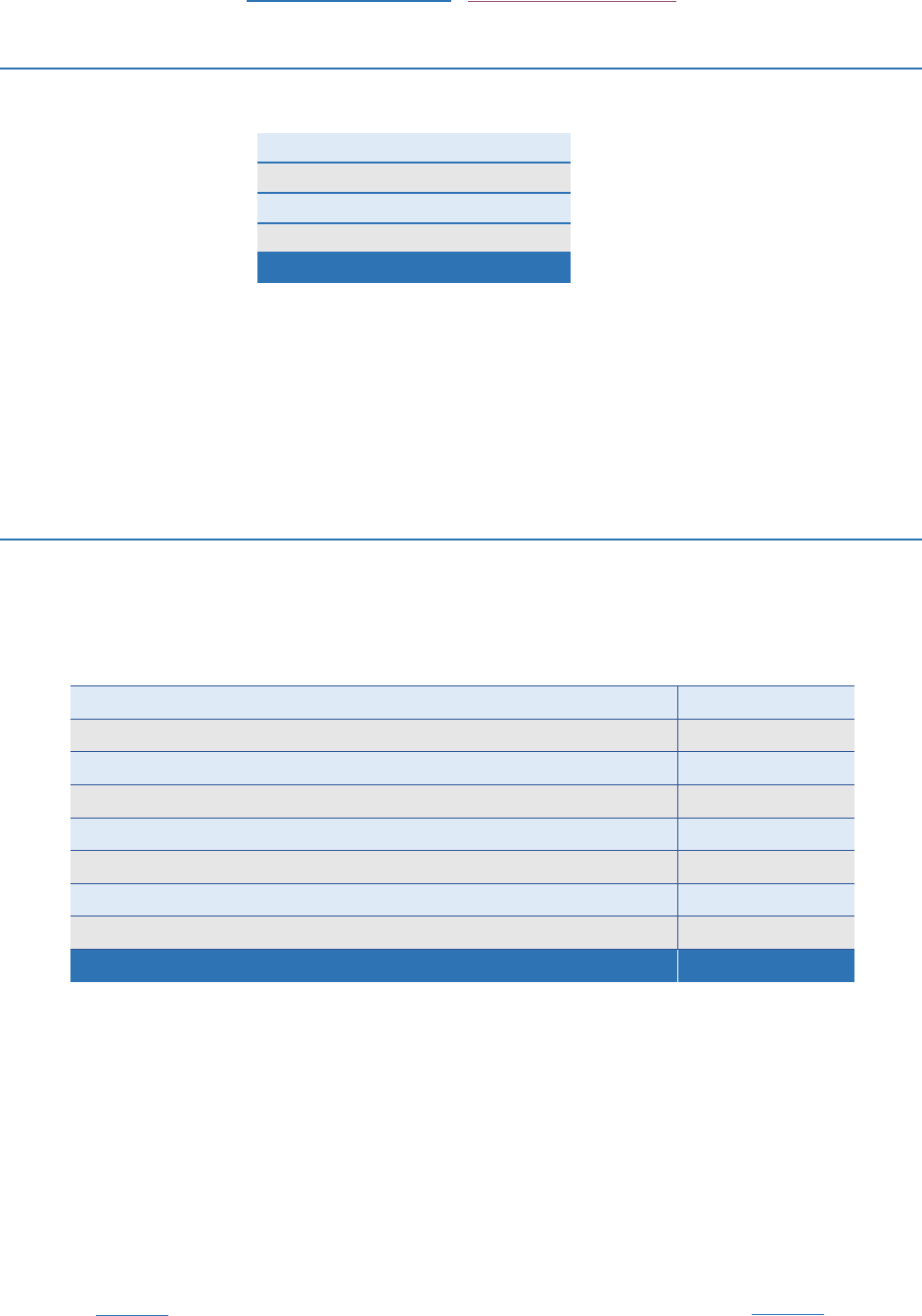

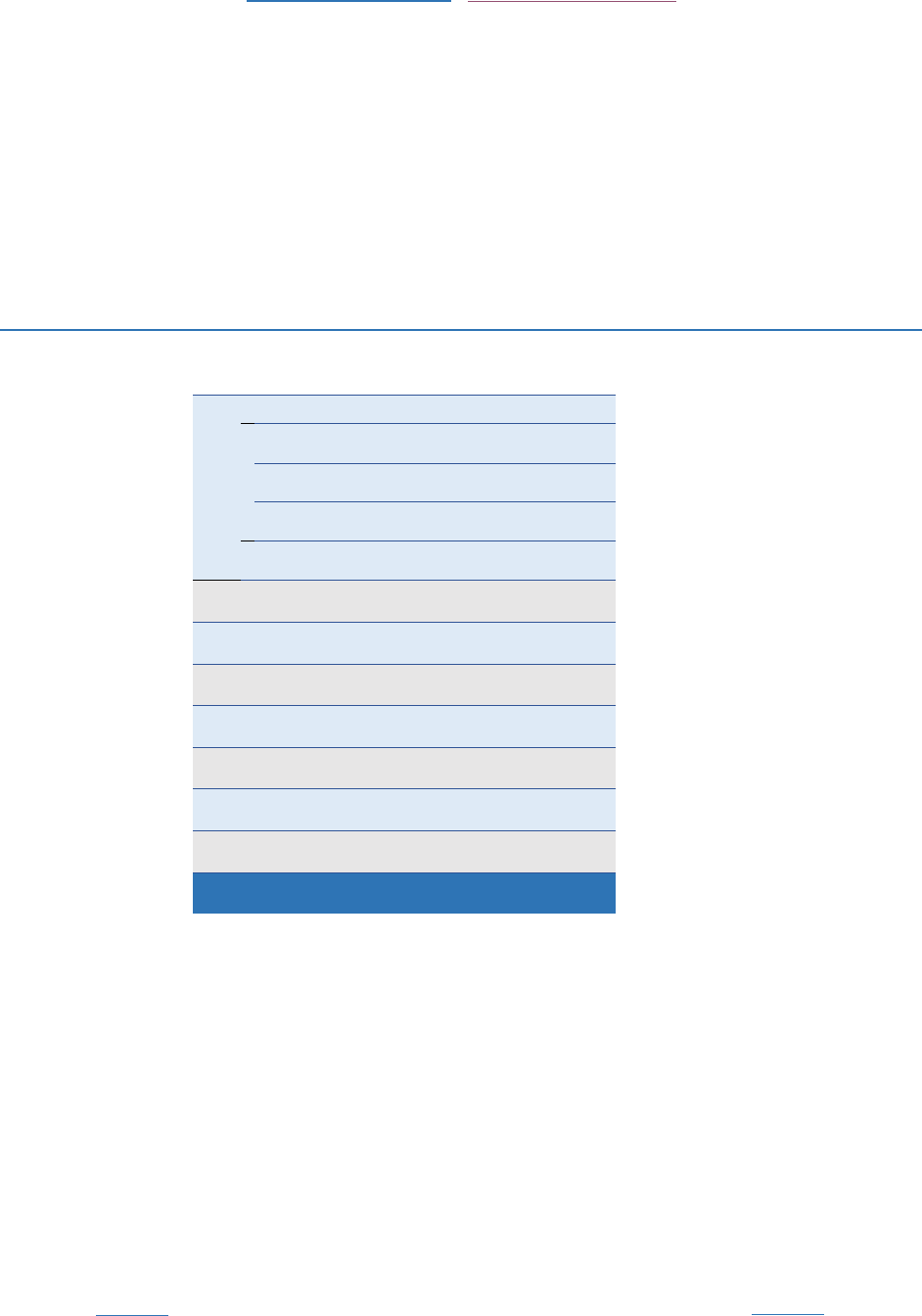

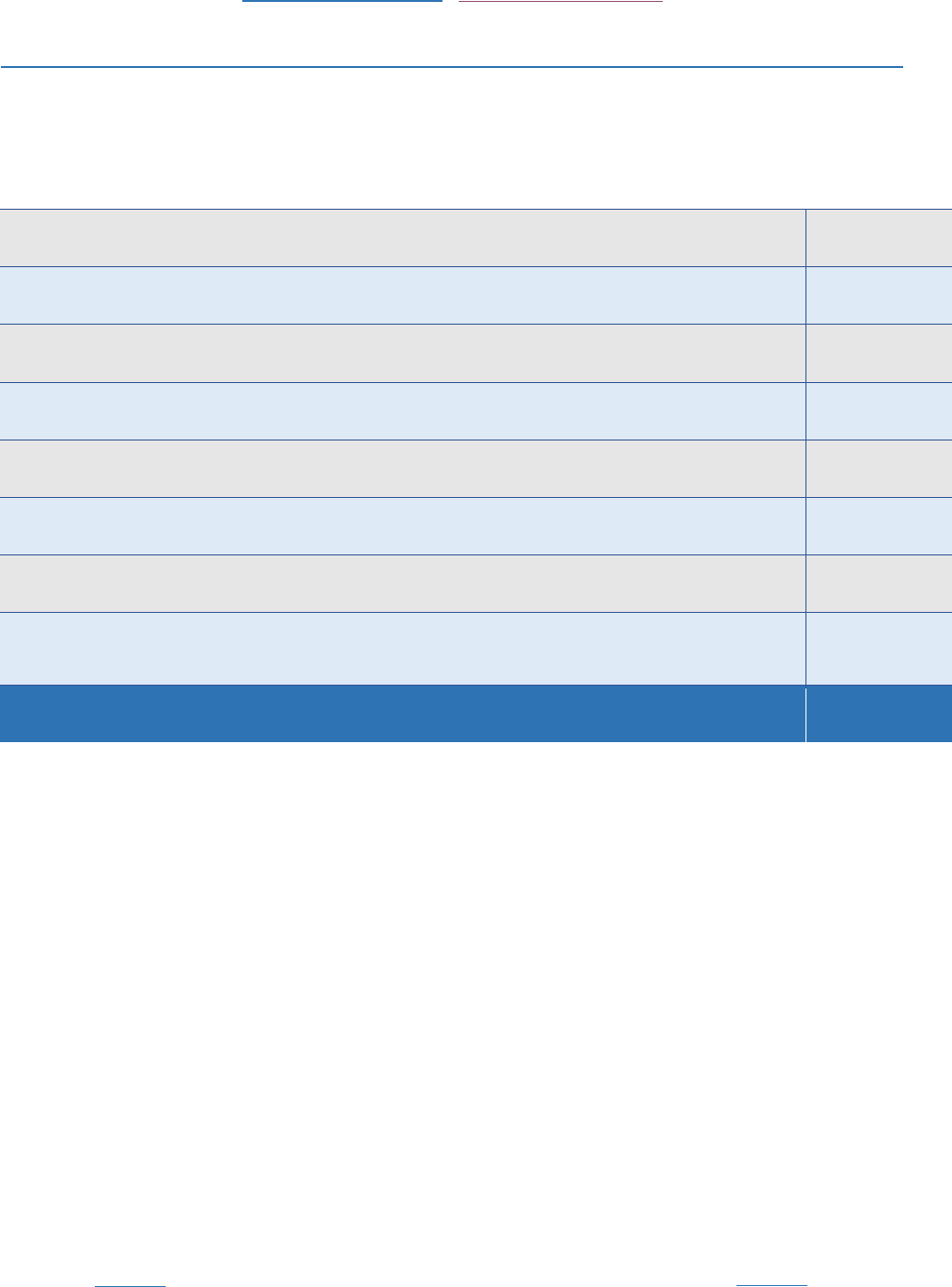

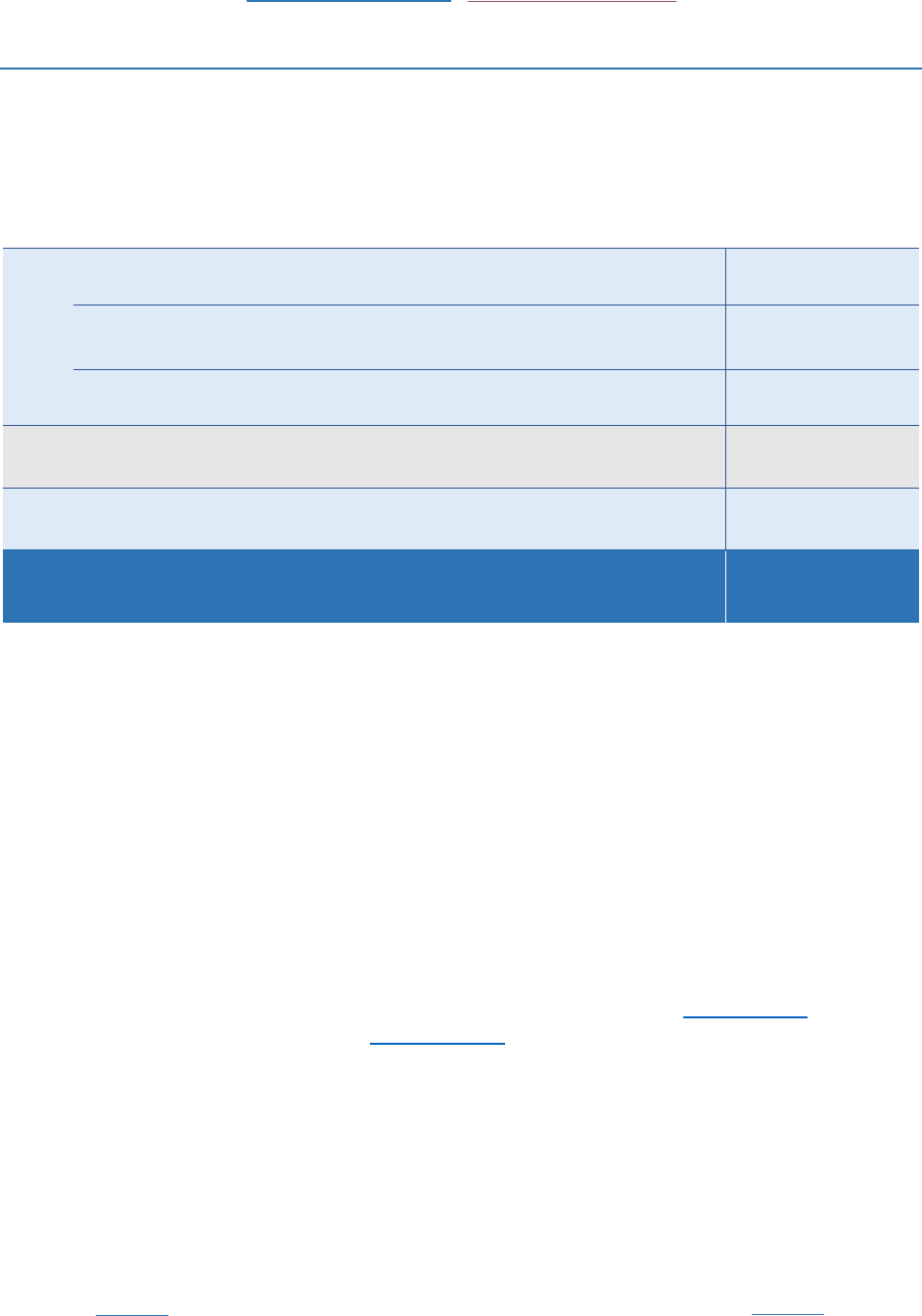

Executive Summary

•

Page

I. Introduction

1

II. Background

3

Misconduct by law enforcement has received a great deal of attention as a result

of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has focused on racial discrimination

and violence by police officers. We study a different (but overlapping) type of

behavior: misconduct that distorts evidence in criminal cases and leads to

convictions of innocent people.

3

There is a dearth of prior systematic research on police misconduct that

contributes to false convictions.

3

Prosecutorial misconduct has attracted a good deal of attention in the past decade,

primarily concealing exculpatory evidence. Several studies have found thousands

of criminal cases in which courts or other agencies determined that prosecutors

committed misconduct, but very few were disciplined for it.

3

Our database, the National Registry of Exonerations, is an ever-changing

public archive. We define “exoneration” by the conduct of public officials, and use only

non-confidential data. We list all exonerations we can find, add new cases regularly, and

modify our postings on old cases as we get more information or refine or inquiries.

7

This unique database enables us to examine all exonerations—with data from multiple

sources—to identify many cases of misconduct that cannot be found in official

decisions, and to begin to describe the causes and effects of that misconduct.

8

We cannot, however, estimate rates of misconduct in all criminal cases; and

even among exonerations we miss a great deal of official misconduct that remains

hidden.

8

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page x • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

We do not systematically examine misconduct by criminal defense attorneys

or by judges. That’s unfortunate, especially for ineffective legal assistance by defense

lawyers, which is probably a major contributor to convictions of innocent defendants.

The main reason is that we do not have data that would enable us to speak to those

issues.

9

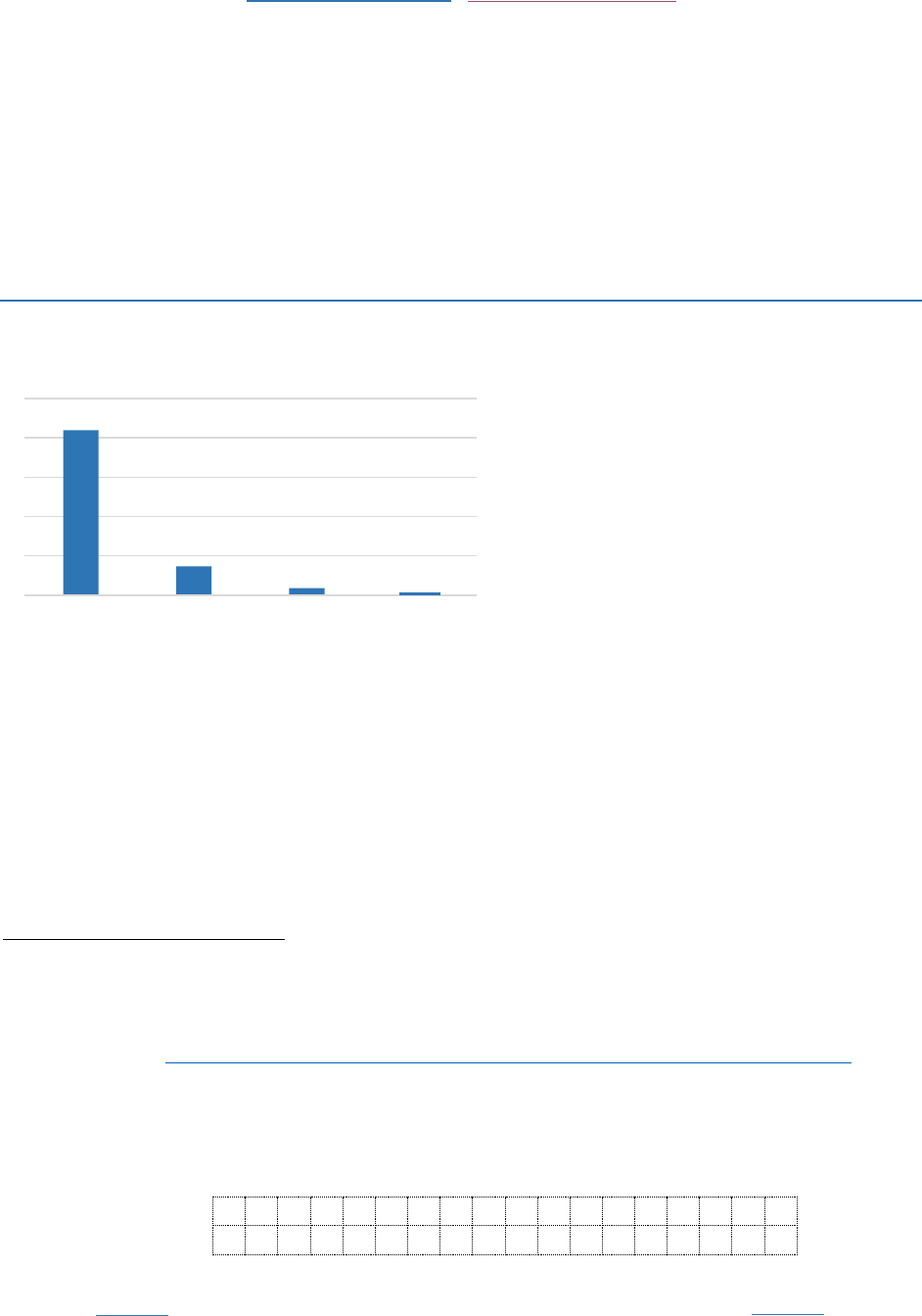

III. The Frequency of Official Misconduct

11

In 54% of exonerations, official misconduct contributed to the false convictions;

usually more than one type of misconduct. Overall, male exonerees and Black

exonerees were modestly more likely to experience misconduct (with some larger

differences by race for a few particular crimes).

11

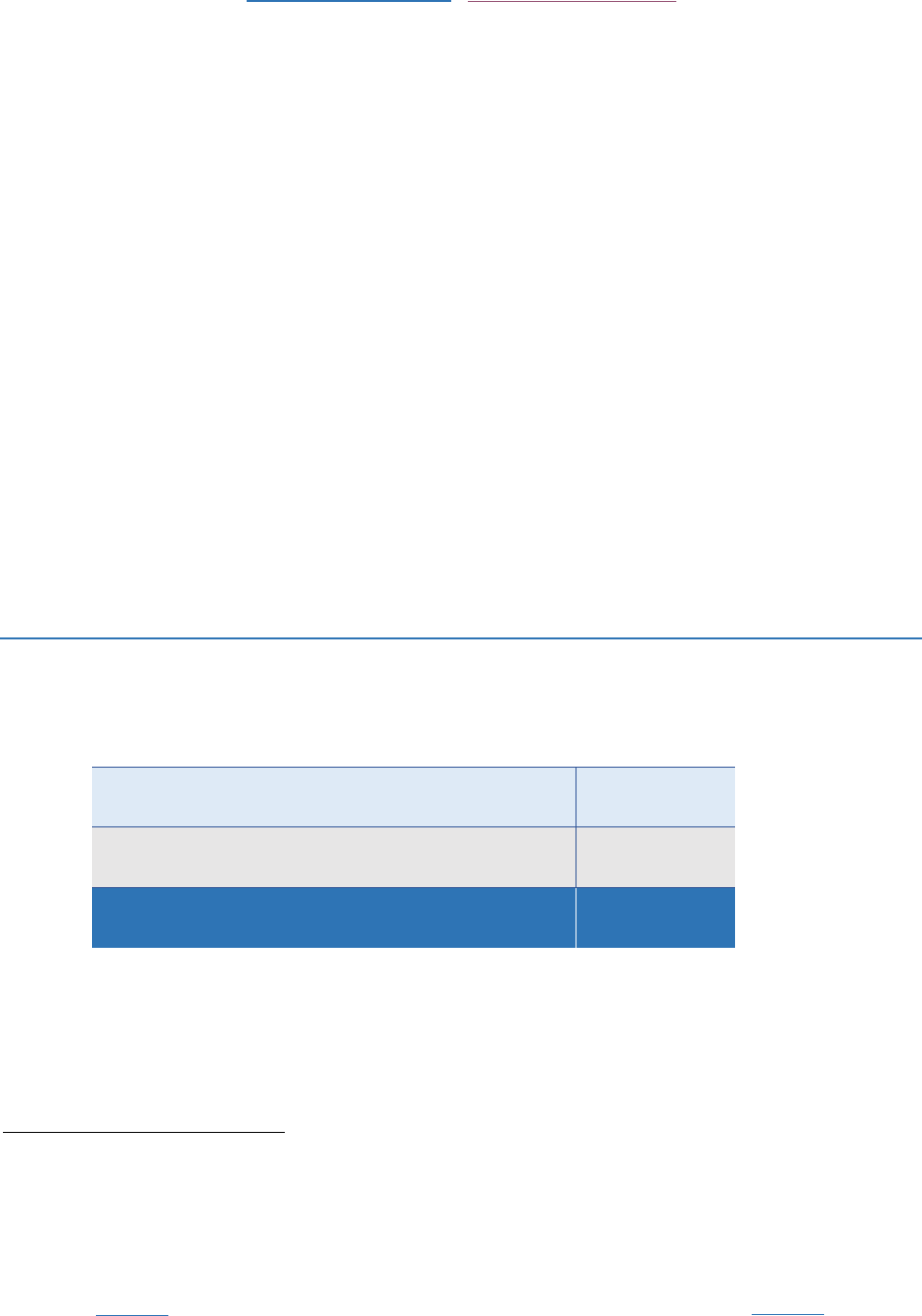

30% of exonerations include misconduct by prosecutors, 35% misconduct by

police, 3% by forensic analysts, and 2% by child welfare workers.

12

The overall rate of misconduct varies by crime, from 72% in murder cases to 32% for

most non-violent crimes. For most crimes, the rates of misconduct for prosecutors

and police are comparable. However:

12

• For drug crimes, the rate of police misconduct is nearly four times the rate of

misconduct for prosecutors.

13

• In white-collar exonerations, prosecutorial misconduct is more than five

times as frequent as misconduct by police. This gap is entirely due to the

extremely high rate of misconduct by federal white-collar prosecutors.

13

We only count misconduct that contributed to the exonerees’ false

convictions by generating false evidence of guilt or concealing true evidence of

innocence. We don’t count misconduct that can’t produce false evidence—for example,

police brutality that was not part of an interrogation—or failed attempts to produce false

evidence, such as torturing a suspect who does not confess.

13

Violent felonies account for nearly 80% of exonerations. Misconduct is generally

more common the more extreme the violence, ranging from 38% and 39% for robbery

and sexual assault cases to 72% for exonerations from death sentences. These

numbers reflect both higher rates of official misconduct in the most serious

crimes, and more diligent post-conviction reinvestigations.

15

Drug crimes make up more than 60% of exonerations for non-violent crimes. Two-

thirds of them occurred in two very different local clusters:

20

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• In Chicago, 66 convicted drug offenders were exonerated after it was shown

that officers under the command of a corrupt police sergeant or his subordinates

planted evidence on them. All of those cases involved police misconduct.

21

• In Harris County, Texas (Houston), 149 defendants who pled guilty to drug

crimes were exonerated after lab tests found no illegal drugs in the materials

seized from them. Only 3% of those cases involved misconduct.

24

White-collar crimes—the second largest group of exonerations for non-violent

offenses—are primarily federal cases with a very high rate of prosecutorial

misconduct.

26

About 80% of criminal convictions in the United States are misdemeanors, but only

about 4% of exonerations, and two-thirds of those are Harris County drug crime

guilty plea cases. The remaining sliver of misdemeanor exonerations—about 1% of the

total—have a high rate of official misconduct, 58%.

26

Overall, exonerations of Black defendants have a slightly higher rate of misconduct

than those of white defendants, 57% to 52%. But the differences are greater for

murder cases (78% to 64%)—especially those with death sentences (87% to 68%)—

and drug crime exonerations (47% to 22%).

28

Almost all the official misconduct we have identified falls into five general categories

that we discuss in detail in the sections that follow:

29

1. Witness tampering occurred in about 17% of exonerations.

30

2. Misconduct in interrogations occurred in 57% of all exonerations with

false confessions, or about 7% of all cases.

31

3. Fabricating evidence happened in about 10% of cases, in three forms:

Forensic fraud—in 3% of exonerations, police officers or forensic analysts

lied about forensic evidence. Fake crimes—in 4% of exonerations, police

planted drugs or guns on innocent suspects, or lied and said the suspects had

assaulted them. Fictitious confessions—in about 2% of exonerations,

officers fabricated confessions from defendants who did not confess.

31

4. Concealing exculpatory evidence is the most common type of official

misconduct we found. It occurred in 44% of all exonerations.

32

5. Misconduct at trial occurred in about 23% of exonerations, about evenly

divided between perjury by law enforcement officers, 13%, and trial

misconduct by prosecutors, 14% (with some overlap).

33

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Misconduct in interrogations occurred overwhelmingly in murder

exonerations; concealing exculpatory evidence and misconduct at trial were

most common in murder cases, followed by white-collar crimes; witness

tampering was slightly more common among exonerations for child sex abuse

exonerations than for murder; and fabricating evidence was several times

more common among exonerations for drug crimes than for any other crime.

30

• IV. Witness Tampering

34

Witness tampering occurs when a law enforcement officer tricks, persuades or

forces a witness to testify falsely against the defendant. The officer need not know

that the witnesses is testifying falsely as long as the officer does not care whether the

witness is telling the truth.

34

Witness tampering occurred in 17% of exonerations. In 5%, witnesses were forced to

give false testimony by threats, in 13% they were manipulated into doing so without

threats. (1% of cases included both types of tampering.)

35

Witness tampering occurred most often in child sex abuse cases, 28%, and murder

cases, 23%. Police participated in witness tampering in 80% of cases where it

occurred, prosecutors in 31% and child welfare workers in 14%.

35

About four-fifths of witness tampering falls into one of three categories:

1. Procuring false testimony—inducing a witness to testify to facts the

officer or prosecutor knows the witness did not perceive.

2. Tainted identifications—inducing a witness to identify a suspect at an

identification procedure, whether or not the witness recognizes the suspect.

3. Improper questioning of a child victim—repeated, insistent and

suggestive questioning of a child by officials who will not allow the child to

deny that s/he was a victim of sex abuse.

36

Procuring false testimony, with or without threats, means obtaining testimony that

both law enforcement and the witness know is false. It occurred in 6% of

exonerations, two thirds of them murder cases. Police were involved about twice as

often as prosecutors.

37

A suggestive identification procedure—for example, giving a witness a single picture

of a suspect to identify—may easily cause misidentifications, but that alone is not

misconduct. A tainted identification occurs when an officer directly or indirectly

“tells” a witness who to identify as the criminal.

39

Tainted identifications occurred in about 6% of exonerations. Three quarters were

murder and sexual assault cases; almost all were obtained by police.

39

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xiii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• In 80% of murder cases with tainted identifications, at least one witness

deliberately misidentified the exoneree; many were forced to do so.

40

• In all but one sexual assault exonerations, victims or other witnesses were

persuaded or tricked into misidentifying the exonerees by mistake; in one

case, the identification was produced by threats.

41

Improper questioning of a child victim occurred in about a quarter of child sex

abuse exonerations, primarily cases from the epidemic of child sex abuse hysteria

prosecutions in the early 1980s to the late 1990s.

41

• Police participated in improper questioning of child victims 85% of the time,

and child welfare workers did so in 71% of the cases. Most of the children

were questioned by more than one type of official.

36

• Some children who eventually testified against exonerees came to believe

their accusations; others have said that they knew that they were lying.

43

• V. Misconduct in Interrogations

45

In 12% of known exonerations—mostly murder cases—convictions were based on

false confessions by the exonerees. 57% of false confessions were obtained by

misconduct in interrogations.

45

Misconduct in interrogations is defined (if not clearly) by the Supreme Court.

Beginning in the 1940s, the Court developed an increasingly strong prohibition against

violence in interrogations. Otherwise, an interrogation violates due process of law if

under the “totality of the circumstances” it is deemed so coercive that the resulting

confession is “involuntary.”

48

False confessions are far more common in Chicago than elsewhere. In the rest

of the country, 10% of all exonerations and 18% of murder exonerations included false

confessions; in Chicago the comparable figures are 33% and 54%.

47

The same is true of misconduct in interrogations: 77% of false confessions in Chicago

were obtained by misconduct, compared to 49% elsewhere.

49

Actual or threatened violence was used in 64% of interrogations with

misconduct—36% of all exonerations with false confessions—as often as all

other forms of misconduct in interrogations combined.

50

The concentration of violence in interrogations in Chicago is particularly stark.

Violence was used to obtain 69% of false confessions in exonerations in Chicago,

but only 24% elsewhere. Half of all exonerations in the country with false

confessions that were obtained by violence are from Chicago.

50

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xiv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Much of the violence in interrogations in Chicago was due to a systematic program of

torture of Black suspects in the 1970s and 80s by Chicago Police Commander Jon

Burge and his subordinates (see Section XII).

50

Some lies, promises and threats in interrogations are permitted, and some are

prohibited. The distinction can be elusive. Other than violence, most misconduct in

interrogations consisted of prohibited lies, promises or threats.

48

53

Interrogators are allowed to lie about the facts of the investigation (“we found your

fingerprints”) but not about the law (“you’ll get sentenced to death”). They may make

vague promises (“if you confess, we can help you”), but not specific ones they can’t

keep (“if you confess, the DA won’t ask for the death penalty”). In 20% of exonerations

with false confessions, the police lied about the law or promised outcomes they

couldn’t deliver.

48

53

Police may threaten to arrest a suspect who does not confess—an act within their

power—and prosecutors may threaten to prosecute one who does not cooperate.

But threats against third parties—e.g., to arrest a spouse or child of the suspect, or to

remove minor children from her home—are prohibited. Third-party threats were

used in 8% of exonerations with false confessions.

46

48

54

Several permitted interrogation practices also contribute to false confessions:

55

• Permissible promises and threats.

• Lying about the investigation.

• Telling the suspect details of the crime (which makes it hard to separate

true confessions from false ones generated by the police).

• Interrogating a juvenile without a parent or guardian present.

One or more of these practices contributed to 70% of false confessions: 79% of those

obtained with misconduct and 57% of those obtained without it.

60

Confessions by actual or possible codefendants of the exonerees falsely

implicated exonerees in about 13% of cases.

60

Many codefendants voluntarily confessed and implicated exonerees, usually to shift

some blame away from themselves. About a third of codefendant confessions that

contributed to false convictions were obtained by the same types of misconduct that

produced most false confessions by the exonerees themselves.

61

In a third of exonerations with codefendant confessions, the exoneree also

confessed; in the rest, the exoneree did not. The net effect is that all false

confessions—by codefendants as well as by exonerees themselves—contributed to

the convictions in 21% of exonerations.

60

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

As with false confessions by exonerees, false codefendant confessions that helped

convict exonerees were concentrated in murder cases, and in Chicago.

61

• VI. Fabricated Official Evidence

65

In 10% of exonerations, officers falsely reported that they examined forensic

evidence that proved (or failed to disprove) the defendants’ guilt, saw the defendants

commit crimes that did not occur, or witnessed confessions by defendants who

did not confess.

65

Forensic fraud—the deliberate falsification of forensic evidence to help convict a

defendant—occurred in 3% of exonerations.

65

• Forensic fraud is a form of intentional misconduct. We do not count a

larger set of cases with forensic evidence that was (as far as we know)

unintentionally mistaken, misleading, or invalid.

65

• We only count forensic fraud by law enforcement officers, usually forensic

examiners at police crime labs or other state-run labs.

65

• There are many types of forensic fraud, but these are the most common:

1. In more than a third of the cases, analysts reported that the defendant’s

hair, saliva, blood, semen, tooth marks, etc., matched or were

consistent with those found at the crime scene, when in fact testing

had shown the opposite.

65

2. In about a quarter of the cases, forensic witnesses reported that the

defendants might have been the source of crime-scene blood, semen

or fingerprints, after forensic tests that showed that was impossible.

65

• A third of forensic fraud cases involve repeat offenders, possibly because

they are more likely than other wrongdoers to eventually get caught, after which

many of their prior cases are reexamined.

67

Fake crimes were fabricated by police in about 5% of exonerations:

68

• In about 4%, police planted evidence at the scene of the crime and claimed to

have found it there. In all but a few cases, they planted illegal drugs—especially

in a cluster in Chicago (see above, Section III.3.c.i).

68

• In about 1%, officers falsely claimed that the defendants assaulted them,

usually to cover up their own violence against the same defendants.

69

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xvi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Fabricated confessions: In about 2% of exonerations, police made up confessions

from exonerees who did not confess.

70

• In several cases, police had exonerees sign documents they did not or could

not read, which later turned out to be confessions. In most cases, they lied and

said the exonerees made unrecorded oral confessions.

70

• As usual for false confessions, fabricated confessions were more likely in

Chicago than elsewhere, but by a modest amount, 16% to 11%.

72

• VII. Concealing Exculpatory Evidence

74

Concealing exculpatory evidence contributed to the convictions of 44% of

exonerees, more than any other type of official misconduct we know of.

75

The legal duty to disclose exculpatory evidence has multiple bases:

75

• In Brady v. Maryland, in 1963, the Supreme Court announced the

‘Brady rule’: “[S]uppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to the

accused… violate[s] due process where the evidence is material either to guilt or

to punishment.”

75

• Brady only applies if the concealed evidence is “material”—which, in this

context, means that the outcome of the trial would likely have been different if

that evidence had been known. This requirement has been widely criticized as

incoherent, inconsistent and unadministrable.

75

• In addition, rules of professional responsibility and pretrial discovery

that govern criminal cases also require the prosecution to disclose all

exculpatory evidence, regardless of “materiality.”

78

• We apply these procedural and ethical rules—and classify hiding evidence

as misconduct regardless of “materiality”—because they prescribe correct

conduct rather than define a violation of the constitution. (Plus, we too could not

classify “materiality” consistently if we tried.)

80

The rate of concealing exculpatory evidence varies by crime, from 61% for murder

to 27% in child sex abuse cases. It is so common and widespread that it happened

in 82% of all exonerations with any official misconduct.

81

Prosecutors concealed exculpatory evidence in 73% of cases in which it occurred.

That’s not surprising, since prosecutors have the duty to disclose that evidence to

the defense. We only count other officials as responsible if (as far as we know)

prosecutors were ignorant of the evidence.

82

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xvii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Police concealed exculpatory evidence in 33% of cases where it occurred (including

cases with concealing by more than one type of official), and forensic analysts did so

in 6%. In some portion of those exonerations, prosecutors did know about the concealed

evidence, but we have no record of that knowledge.

82

As far as we know, only 13% included concealed physical objects—clothing,

weapons, etc. This gap may in part reflect how effectively objects can be destroyed or

hidden, but information may linger in electronic or physical files, or the memories

of people.

83

In 63% of cases with concealed exculpatory evidence, substantive evidence of the

exonerees’ innocence was hidden—evidence that in itself helps prove the defendant’s

innocence, such as an eyewitness who named another person as the criminal.

85

In 80% of such cases, impeachment evidence that undermined testimony by

prosecution witnesses was concealed—for example, evidence that a witness who

identified the exoneree as a murderer told his brother he never saw the killing.

85

In half the exonerations with concealed exculpatory evidence, both substantive and

impeachment evidence were hidden. Often, a single item of evidence serves both

functions. “Substantive” evidence may sound more important, but concealing

impeachment evidence that eviscerates the credibility of a critical prosecution witness

can be devastating to an innocent defendant.

85

Predictably, law enforcement officials usually conceal their own misconduct. That’s

misconduct in itself, derivative concealment. For example, it’s misconduct for an

officer to plant drugs on a suspect, and it’s a separate act of misconduct to conceal

the officer’s knowledge that the suspect is innocent.

85

Evidence of other official misconduct was concealed in 26% of all exonerations,

over half of exonerations with any concealed exculpatory evidence.

88

A large variety of types of exculpatory evidence were concealed, but most fall into

several categories.

89

Impeachment evidence:

• Incentives to testify against the exonerees were concealed in 21% of

exonerations, most often deals on criminal charges against the witnesses.

89

• Inconsistent statements by prosecution witnesses that contradicted their

testimony were concealed in 14% of exonerations.

90

• Criminal records and histories of dishonesty of witnesses for the state

were concealed in 4% of exonerations.

90

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xviii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Substantive Evidence:

91

• Exculpatory forensic tests were concealed in 6% of exonerations, including

many that conclusively established the exonerees’ innocence.

91

• Alternative suspects were concealed in 12% of all exonerations—20% of

murder exonerations and 6% of other cases.

92

• Exclusions by an eyewitness—evidence that an eyewitness said the exoneree

is not the criminal—was concealed in 2% of exonerations.

92

• Alibi evidence was concealed in 1% of exonerations.

94

• Evidence that no crime was committed was concealed in 6% of exonerations,

mostly cases where police concealed the fact that they themselves framed the

defendants.

94

• VIII. Misconduct at Trial

96

At least 95% of criminal convictions in the United States are obtained by guilty

pleas rather than trial verdicts, but 80% of exonerations in the Registry followed

conviction at trial. About 28% of those trials (23% of all exonerations) included

official misconduct in court.

96

Police perjury

96

• Perjury by all law enforcement officials occurred in 14% of the trials at

which exonerees were convicted, or 13% of all exonerations (including those

after guilty pleas). In about a quarter of those cases, officials lied about forensic

testing, or about things the officials themselves claimed to have witnessed the

exonerees do or say. (See above, Section VI.)

96

• Perjury by police officers occurred in 11% of trials of exonerees. In 9% of

those trials (7% of all exonerations), officers lied about information

obtained from others.

97

• Most often, police lied about the conduct of the investigations: what a

witness had said, whether or how a lineup was conducted, etc. The most

common subject of police perjury was the conduct of interrogations at which

innocent defendants confessed.

97

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xix • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• We miss a great deal of police perjury. We rarely have access to

transcripts or other detailed information about trial testimony, so we only

learn about perjury at trial if it becomes a conspicuous issue.

98

Trial Misconduct by Prosecutors

98

• Permitting Perjury

98

❖ In 1959, the Supreme Court held that a prosecutor has a

constitutional obligation to correct perjury by a state witness even

if she did not herself offer the false testimony.

99

❖ Prosecutors permitted perjury to go uncorrected in 8% of

exonerations. In most cases, the perjury was by civilian witnesses. The

most common lies were about favorable treatment the witnesses

receive in pending criminal cases of their own.

99

• Lying in Court

100

❖ It is misconduct, and punishable as contempt of court, for a lawyer to

lie in court, whether or not the lawyer in under oath.

101

❖ We know that prosecutors lied in court in 4% of exonerations. The

real rate may be higher since we only count cases with clear evidence

that prosecutors made statements they knew were false.

102

❖ About half of lies by prosecutors were made in closing argument. A

common pattern is to repeat and affirm perjury by a witness that the

prosecutor knew about but failed to correct—for example, a lie by a

witness who claimed to have no deal with the prosecutor.

102

• Improper Statements in Closing Argument or Cross-examination

103

❖ Prosecutors also commit misconduct at trial without lying, usually

in closing arguments or in questions on cross-examination.

103

❖ Prosecutors made improper closing arguments (without lying) in

3% of exonerations, ranging from statements that the prosecutor “knows”

the exoneree is guilty to outright appeals to bigotry.

104

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xx • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

❖ Prosecutors asked impermissible questions on cross-examination in

1% of exonerations.

106

❖ Both forms of misconduct are undoubtedly much more common

than we know. They are only visible if the defense objects at the time,

and lawyers often fail to do so, intentionally or by neglect.

104

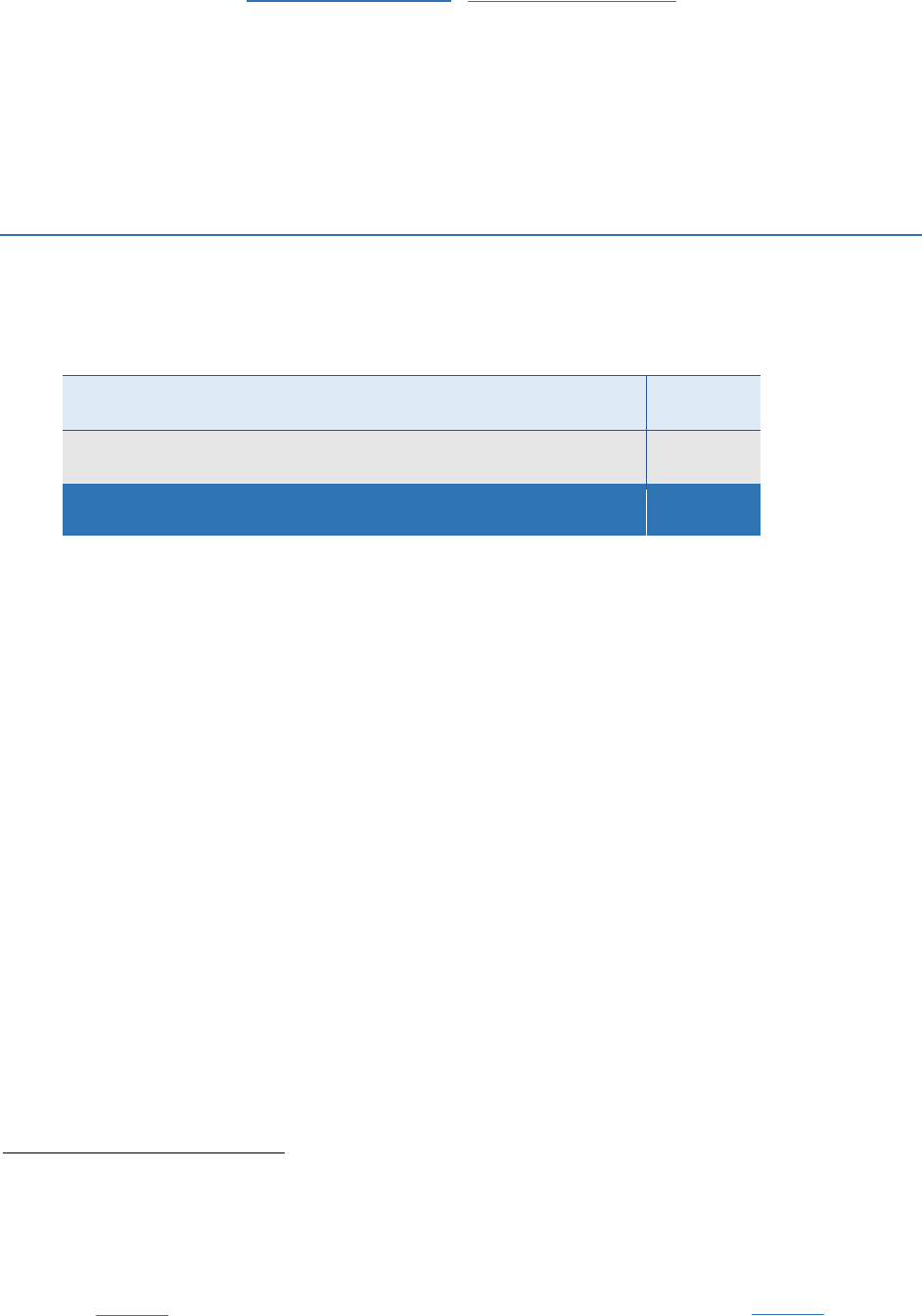

• IX. Federal Cases

108

Federal crimes are a small and unrepresentative minority of all criminal cases in the

United States. They generate about 6% of convictions, heavily skewed to immigration,

drug and white-collar crimes.

108

Federal exonerations are a comparably small minority of all exonerations, and

equally skewed: 41% are white-collar crimes, and another half are about evenly split

between drug and violent crimes.

108

The overall rate of official misconduct is somewhat higher in federal exonerations

than in state cases, 61% compared to 54%.

109

Most misconduct in federal exonerations was committed by prosecutors, 52%

compared to 29% in state cases.

109

Federal prosecutors committed misconduct in exonerations more than twice as

often as police (52% to 20%), while state prosecutors committed misconduct less

often than police (29% to 36%).

109

Federal white-collar exonerations have striking similarities to murder

exonerations under state law. They are the most common types of exonerations in

their respective courts; many are big-ticket cases—expensive, long-running,

conspicuous; they have the highest rates of misconduct for exonerations in those

courts, 65% for federal white-collar crimes, 72% for state-court murders.

110

In federal white-collar exonerations, prosecutors committed misconduct more

than 7 times as often as police, 65% to 9%; every federal white-collar exoneration

with any official misconduct included misconduct by a prosecutor.

112

Federal white-collar cases have both the highest rate of misconduct by

prosecutors and the lowest rate of misconduct by police of exonerations in any

crime category.

112

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

Federal white-collar prosecutors seem to play a more dominant role in cases

that lead to exonerations than state prosecutors. They have more resources, and are

more likely to take the lead in the investigations. That role may reduce police

misconduct—but not misconduct by the prosecutors themselves.

113

• X. Discipline

115

In 17% of exonerations with official misconduct, we know that some form of

discipline was imposed on officials who participated in that misconduct.

115

Many officials who were disciplined committed misconduct in several or many

exonerations, but formal discipline was limited to one, or was imposed in a separate

case. Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge, for example, was sentenced to prison for

lying about the torture program he ran. We count that as discipline in all 19 cases in

which he or those he commanded abused the exonerees. In 70% of exonerations with

discipline, it was imposed for general patterns of behavior or in cases other than the

specific ones at hand.

115

Discipline may be imposed by three sets of authorities: employment discipline by

the agencies that employ the misbehaving officials; professional discipline by

regulatory bodies that certify or license their professions (this category includes a few

instances of courtroom discipline of prosecutors by judges); and criminal discipline,

convictions by courts for misconduct that violates criminal laws.

117

Disciplining Prosecutors

119

• Prosecutors are hardly ever disciplined for misconduct that contributes to

false convictions. We know of some discipline for prosecutors in 4% of

exonerations with prosecutorial misconduct. In most of those cases, the

discipline was comparatively mild.

120

• Eleven prosecutors were disciplined by the offices that employed them, but

just two were fired (and four resigned or retired); 14 were disciplined by bar

authorities or courts, but only three were disbarred. Only two prosecutors

have been convicted of crimes for misconduct in exonerations, both in

notorious cases, and both received nominal sentences.

120

Disciplining Police

121

• Police officers were disciplined in 19% of exonerations with police

misconduct, about five times the rate for prosecutors.

119

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• In almost 80% of these cases, officers were convicted of crimes; in 20% they

were disciplined by the police forces for which they worked. We know of no

professional discipline of police officers.

120

• In 127 exonerations, police officers who committed misconduct were

convicted of crimes for misconduct of the sort they committed in those cases—

but not 127 separate officers. As we explained, the conviction of a single serial

offender may count as discipline in many cases.

121

• Even so, at least 30 officers were convicted of crimes (compared to two

prosecutors) and some received long prison sentences.

122

• Disciplinary records of police officers are often concealed by their

employers, unions, and professional agencies. As a result, we have no doubt

missed cases of employment and professional discipline of police.

122

Disciplining Forensic Analysts

124

• Forensic analysts were disciplined in 47% of exonerations in which their

misconduct was discovered, a much higher rate than prosecutors or police.

Four-fifths of them were disciplined by their employers, a fifth by

professional agencies, and a few were convicted of crimes.

124

• As with police, several analysts who were disciplined were repeat offenders,

each of whom participated in multiple cases. We know of 35 exonerations with

discipline for forensic misconduct, but only 13 separate analysts were punished,

six of whom accounted for 80% of the cases.

124

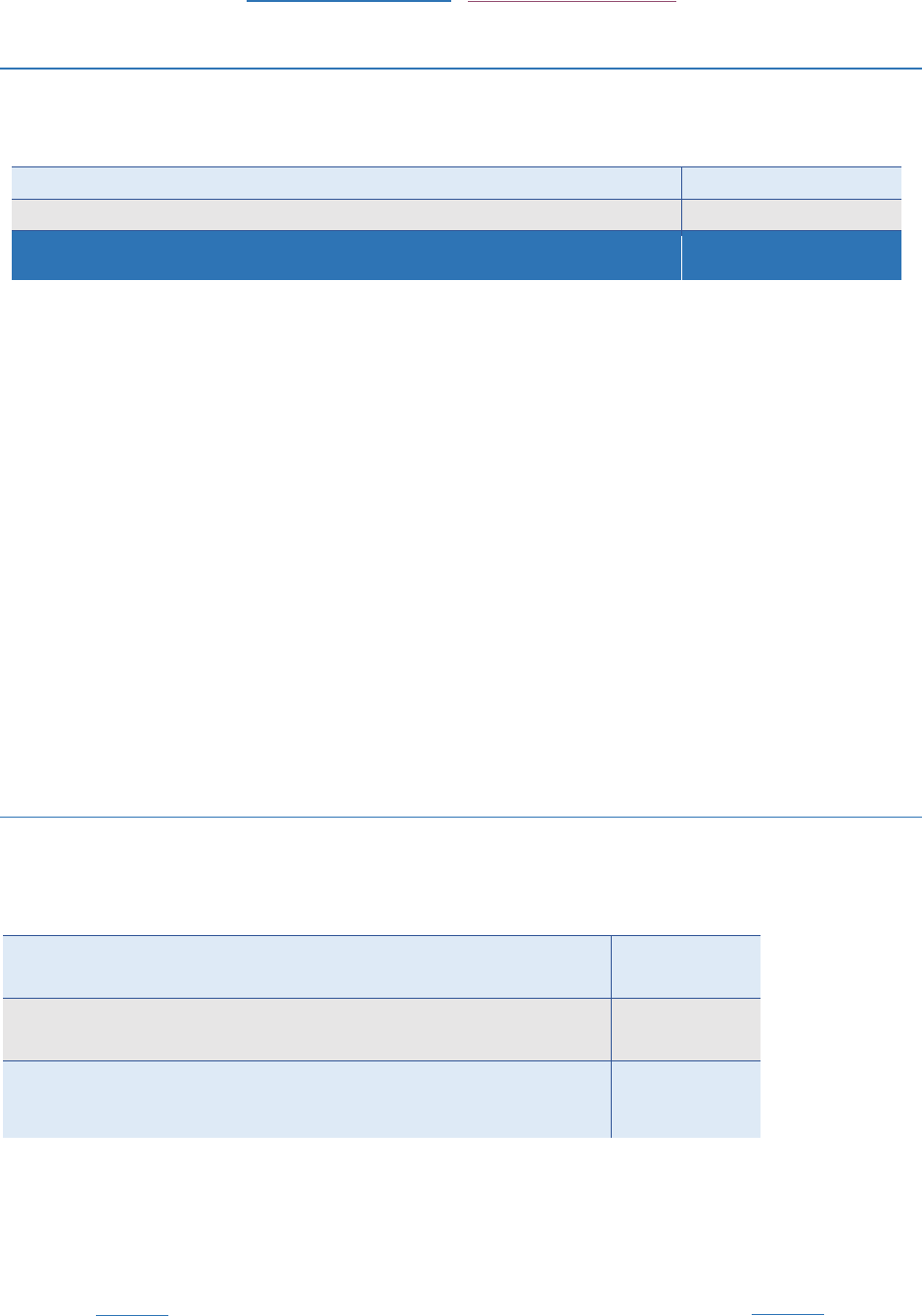

• XI. Changes in Official Misconduct over Time

127

It is difficult to detect decreases in misconduct in exonerations because of the long

time lag from conviction (the last date for occurrence of misconduct) to

exoneration (the earliest date when the misconduct can be added to our data).

127

For example, there were six times more exonerations with misconduct in murder

convictions in the 16 years from 1987 through 2002 than in the 16 years from 2003

through 2018—but because the average time to exoneration for such cases is 17

years, more cases from the later period will continue to emerge for years.

128

In three contexts, official misconduct decreased so sharply that we believe the

decline is real despite the difficulty of identifying decreases:

128

• Improper questioning of child victims all but stopped after the end of the

child sex abuse hysteria epidemic that ran its course in the late 1990s.

129

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxiii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• Misconduct in interrogations, especially violence, has dropped to a small

fraction of what we saw for convictions before 2003.

129

• Forensic fraud has declined sharply in all exonerations from convictions

since 2003, and among those with forensic evidence problems.

130

On the other hand, the rate of federal white-collar crime exonerations with official

misconduct has doubled among exonerations for convictions since 2003.

131

• Increases in misconduct—unlike decreases—are not hard to spot. In fact,

since more exonerations in recent cases with misconduct will continue to occur,

the size of an observed increase will go up over time.

131

• XII. Discussion and Conclusions

133

Why do Law Enforcement Officials Commit Misconduct?

133

We address this question by examining the conduct of the officials who committed or

permitted misconduct that led to many false convictions.

We conclude that the main causes are systemic: pervasive practices that permit or

reward bad behavior; lack of resources to train, supervise and conduct high

quality investigations and prosecutions; and ineffective leadership by police

commanders, crime lab directors and chief prosecutors.

133

• Ken Anderson, was the district attorney of Williamson County, Texas, who

prosecuted Michael Morton for the murder of his wife, and obtained a life

sentence in 1987. Anderson concealed potent exculpatory evidence that

could have cleared Morton and led to the real killer—who killed another

woman in 1988. Morton was exonerated by DNA in 2012.

134

❖ Why did Anderson conceal this evidence? Our best guess is that he

believed Morton was guilty, paid little attention to evidence to the

contrary—and concealed that evidence because that was his regular

practice, it made winning easier, and no one had stopped him before.

135

❖ Anderson set the tone for his office. We know that one subordinate

followed Anderson’s lead and concealed evidence to convict an

innocent defendant. There were probably others.

135

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxiv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• Richard M. Daley was chief prosecutor in Chicago in 1982 when he received

a detailed report of torture of a murder suspect by then Chicago Police

Lieutenant Jon Burge, who ran a systematic program of torturing suspects,

mostly Black men, in the1970s and ‘80s. Daley ignored it, and his office

continued to use confessions that Burge obtained by torture.

136

❖ Why did Jon Burge act as he did? Sadistic racists exist, and some

become police officers. The real question is why he was not stopped,

given that many people—including Daley—knew what he was up to.

138

❖ Burge’s superior in the police department could also have stopped

him, but Daley had more power. He could have stopped using

confessions obtained by torture, and he could have prosecuted

Burge and his men for numerous violent felonies—but he didn’t.

139

❖ Why was Burge given free rein? Most likely, Daley and others

thought the defendants were guilty, wanted murder convictions,

didn’t worry about the means—and didn’t mind the torture of Black

men they believed were murderers.

140

• Joyce Gilchrist was fired as a supervisor of the Oklahoma City Police

Laboratory in 2001, after 16 years at that lab. By then, Gilchrist was known to

have committed forensic fraud in several cases. That count has grown to

dozens of forensic fraud cases, including six exonerations.

140

❖ Why did Gilchrist pursue a career in forensic fraud? It made her a

star. She received a citation from the police department, a

commendation from the district attorney, an early promotion, and

was named Civilian Police Employee of the Year.

141

❖ Why were police and prosecutors so enthusiastic about Gilchrist?

They were warned about her, and some thought her results were too

good to be true, but she got convictions other analysts couldn’t—so

they used her.

142

• Officers Iannotto, Palmer, Pecorale, Martin, Visconti and Bishop, and

Detective Massanova all participated in the investigation of a fatal

shooting in New York in November 1990. They soon identified an innocent

suspect and brought him to the scene—in handcuffs and wearing a jacket turned

inside out to resemble the shooter’s jacket—where several witnesses urged each

other to identify him. The next day they put the disheveled suspect in a lineup

with well-groomed police cadets, and he was misidentified again.

143

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

❖ Why did these officers conduct what an appellate court later

describe as “a series of identifications [that] were both improper and

prejudicial”? It seems to have been just routine: they thought they

had the shooter, and got the evidence to convict him in the easiest,

quickest manner.

144

Can We Reduce Official Misconduct in Criminal Cases?

144

We discuss possible changes in three contexts: possible Reforms that affect rules,

resources, and accountability; the Local Leadership and Culture of crime labs,

police forces and prosecutors’ offices; and National Patterns of law enforcement,

as shaped by the federal Department of Justice and by national culture.

144

Reforms

145

• Rules

145

❖ Procedural rules. In response to Michael Morton’s exoneration, the

state legislature provided “open file” discovery in criminal cases in

Texas—a procedural rule regulating conduct after evidence has been

gathered. Such rules may reduce some types of misconduct, if they

are enforced.

145

❖ Evidence-gathering rules specify, for example, how a lineup should

be run, or that interrogations must be recorded. They directly

improve the quality of investigations; they may also prevent

misconduct in investigations more effectively than procedural rules—if

they are obeyed.

145

Resources. In 1992, New York had 2,000 plus murders; in 2018, a wealthier

city had 287. Lack of resources—because of huge caseloads or other reasons—

tempts officials to close cases by cheating, lying and concealing, and makes

suspects vulnerable to misconduct, because police don’t look for evidence

that clears them, and overworked defense lawyers can’t fill the gap.

146

• Accountability. Discipline for misconduct in past exonerations is too slow

and uncommon to prevent much misconduct in other cases. Comparatively

mild contemporaneous sanctions for low level infractions, by the agencies

that employ the officials, are likely to be more effective—but that is a form of

ongoing supervision that requires adequate resources.

149

Local Leadership and Local Culture

153

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxvi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

The American system of criminal justice is run primarily by thousands of

independent local prosecutors, police chiefs and other administrators. Most

reforms depend on their leadership and ability to change local work cultures.

155

• Crime Labs in the United States are usually run by local police departments.

Experts agree that only independent crime labs can eliminate conflicts of

interest and provide reliable technical supervision. In 2014, after a run of

disastrous errors and misconduct, Houston replaced its police lab with a

highly regarded independent lab—after a costly 12-year transition.

156

• Police. There’s wide agreement that police reform in America is hard to

achieve and harder to sustain, in part because of the influence of police

culture. But the reforms that receive most attention concern police authority

over civilians, especially use of force and race relations. Those that concern us—

procedures for conducting criminal investigations—may be easier to

attain.

160

❖ Recorded interrogations are the most effective means for preventing

false confessions and misconduct in interrogations. In 2002, recording

was required in two states; by 2019, it was 24 states and the federal

government (which had prohibited it)—a sea change that was led by

numerous local police forces that adopted the reform before their

states.

162

❖ Improved eyewitness identification procedures prevent both false

convictions and misconduct in identification procedures. By 2020, 31

states had reformed their identification practices in some manner.

As with recorded interrogations, these statewide reforms were adopted

after hundreds, if not thousands, of local police departments did so on

their own.

163

• Prosecutors. Chief local prosecutors are the most powerful actors in

our system of criminal justice. Like police chiefs, they are constrained by local

culture and politics, but they have greater control over their own agencies.

They also have unreviewable power to decide who to charge and for what

crimes, and effectively control the punishments most convicted criminals

receive.

166

• A chief prosecutor can prevent misconduct that causes false convictions in

many ways: order deputies to follow correct procedures; discipline those

who commit misconduct; drop (or not file) cases tainted by misconduct;

prosecute officials who abuse witnesses or suspects or obstruct justice;

reinvestigate past convictions of defendants who might be innocent.

168

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxvii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

• In the past dozen years, more than 60 local prosecutors, many in major

cities, have created Conviction Integrity Units (CIUs) that helped

exonerate hundreds of innocent defendants. Exonerations mostly occur

long after convictions, but may deter some misconduct all the same.

168

• Since 2014, several progressive prosecutors have been elected in major

counties on platforms that include preventing false convictions. All inherited

or created CIUs, and several have enacted policies to prevent future false

convictions: open file discovery, and lists of police officers they will not call

as witnesses because of past misconduct.

169

• Progressive prosecutors might also limit misconduct by police and

forensic analysts by scrutinizing the evidence they present, refusing to

file charges when they have doubts, and if warranted, prosecuting officials for

criminal conduct.

169

• Progressive prosecutors have attracted substantial institutional and

political opposition from police and police unions, from judges, and from other

prosecutors. Their impact will depend on politics: Will those in office be

reelected? Will others join their ranks? Time will tell.

170

National Patterns

172

Even successful reforms by crime lab directors, police chiefs and local

prosecutors will, at best, turn America into a patchwork of counties with widely

divergent practices, some effective at combating misconduct, some not—unless

change takes place at the national level.

172

• The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) can foster reform, lead

by example (as it did on recording interrogations in 2014), and it can take direct

action to curb local police misconduct. Recently, it has retreated on all

fronts.

173

❖ Reforming forensic science. For several years after 2009 DOJ

played a leading role in a coordinated effort to reform the use of

forensic science in the United States. That was terminated in 2017.

173

❖ Policing local police. Federal prosecutions of police officers who

planted drugs on defendants have led to the dismissal of hundreds of

cases, including 66 exonerations in Chicago. Before 2017, DOJ also

obtained 40 decrees requiring police departments to systematically

change their practices—but not since.

175

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxviii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

•

Page

❖ Leading prosecutors by example. Prosecutorial misconduct in

federal white-collar cases is a startling example of bad practice. It’s

more common than in any other category of exonerations, and the

number of exonerations with prosecutorial misconduct has increased

in the past 18 years.

176

• National Culture. We discussed the culture of individual offices and

departments, or particular counties. But culture also exists—and can

change—at a national level.

177

❖ Questioning children. As we discussed, a nationwide practice of

abusive questioning of supposed victims of child sex abuse has

been abandoned since the mid-1990s.

177

❖ Forensic fraud. A similar change may be taking place with forensic

fraud, at least in investigations of violent crimes. The number of known

cases has decreased by more than 90% since 2003.

178

❖ Violence in interrogations. In 1931, a national commission

initiated a program to eliminate violence in interrogations, which

was routine across the country. By the late 1960s, beatings and torture

were rare; since 2003, they’ve nearly disappeared. This was a major

cultural change in criminal investigation in America. We could see

another.

179

Coda: A quick summary of our thoughts on reforms.

181

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxix • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

Table of Contents

I. Introduction ............................................................................. 1

II. Background ............................................................................. 3

1. CONTEXT ....................................................................................................................... 3

2. THIS STUDY ................................................................................................................... 6

a. Our data ........................................................................................................................ 6

b. Advantages and limitations .......................................................................................... 9

III. The Frequency of Official Misconduct .................................. 11

1. IN GENERAL .................................................................................................................11

2. THE COMMISSION AND THE DISCOVERY OF MISCONDUCT ...................................13

3. MISCONDUCT BY CRIME .............................................................................................15

a. Violent Felonies ........................................................................................................... 15

b. Non-violent crimes in general .................................................................................... 20

c. Drug crimes .................................................................................................................. 21

i. Group exonerations: Cook County, Illinois ........................................................... 21

ii. Guilty pleas: Harris County, Texas ..................................................................... 24

d. White-collar Crimes .................................................................................................... 26

e. Misdemeanors............................................................................................................. 26

4. RACIAL PATTERNS ......................................................................................................27

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxx • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

5. CATEGORIES OF MISCONDUCT .................................................................................29

a. Witness Tampering ..................................................................................................... 30

b. Misconduct in Interrogations ...................................................................................... 31

c. Fabricated Official Evidence......................................................................................... 31

d. Concealing Exculpatory Evidence .............................................................................. 32

e. Misconduct at Trial ..................................................................................................... 33

IV. Witness Tampering .............................................................. 34

1. GENERAL PATTERNS IN WITNESS TAMPERING ......................................................35

2. PROCURING FALSE TESTIMONY ...............................................................................37

3. TAINTED IDENTIFICATIONS ........................................................................................39

4. IMPROPER QUESTIONING OF A CHILD VICTIM.........................................................41

V. Misconduct in Interrogations ............................................... 45

1. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................45

a. Misconduct and permissible interrogation techniques ................................................ 46

b. The frequency of false confessions, in Chicago and elsewhere ..................................... 47

2. WHAT COUNTS AS COERCIVE MISCONDUCT IN AN

INTERROGATION? .......................................................................................................48

3. COERCIVE MISCONDUCT IN INTERROGATIONS THAT PRODUCE

FALSE CONFESSIONS .................................................................................................49

a. Violence ......................................................................................................................... 50

i. Torture in Chicago .................................................................................................. 50

ii. Violence in interrogations of suspects with mental disabilities ............................. 53

b. Sham Plea Bargaining and other lies about the law ..................................................... 53

c. Threats to Third Parties ................................................................................................ 54

4. PERMITTED INTERROGATION PRACTICES THAT LEAD TO FALSE

CONFESSIONS .............................................................................................................55

a. Lying about the investigation ..................................................................................... 55

b. Permissible promises and threats .............................................................................. 56

c. Feeding the suspect details of the crime ...................................................................... 57

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxxi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

d. Interrogating a juvenile with no parent present ........................................................ 59

e. General patterns ......................................................................................................... 59

5. MISCONDUCT IN THE INTERROGATION OF CODEFENDANTS ................................60

VI. Fabricated Official Evidence ................................................ 65

1. FORENSIC FRAUD........................................................................................................65

2. FAKE CRIMES ...............................................................................................................68

a. Planted evidence ........................................................................................................... 68

b. Phony assaults............................................................................................................... 69

3. FABRICATED CONFESSIONS......................................................................................70

VII. Concealing Exculpatory Evidence ......................................... 74

1. THE DUTY TO DISCLOSE EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE ..............................................76

a. Brady v. Maryland and the “Materiality” Requirement.............................................. 76

b. Other Legal Bases for the Duty to Disclose................................................................. 78

i. Professional Responsibility ....................................................................................78

ii. Pretrial Discovery ................................................................................................... 79

2. CONCEALING EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE, BY CRIME..............................................81

3. WHO DOES THE CONCEALING? .................................................................................81

4. WHAT WAS CONCEALED? ..........................................................................................83

a. Objects vs. Information ............................................................................................... 83

b. Substantive Evidence vs. Impeachment ..................................................................... 85

c. Concealing Other Misconduct ..................................................................................... 86

5. CATEGORIES OF CONCEALED INFORMATION .........................................................89

a. Impeachment of prosecution witnesses ..................................................................... 89

i. Incentives to testify ................................................................................................ 89

ii. Inconsistent statements ........................................................................................ 90

iii. Criminal records and histories of dishonesty ..................................................... 90

b. Substantive evidence of innocence .............................................................................. 91

i. Forensic tests ........................................................................................................... 91

Go to Executive Summary • Go to Table of Contents

Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent

The Role of Prosecutors, Police and Other Law Enforcement

Page xxxii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 1, 2020

ii. Alternative suspects ............................................................................................... 92

iii. “I don’t see him” and “Not the guy” ....................................................................... 93

iv. Alibi evidence ......................................................................................................... 94

v. No crime ................................................................................................................ 94

VIII. Misconduct at Trial ............................................................... 96

1. POLICE PERJURY ........................................................................................................96

2. TRIAL MISCONDUCT BY PROSECUTORS ..................................................................98

a. Permitting Perjury ........................................................................................................ 98

b. Lying in Court ............................................................................................................. 100

c. Improper Statements in Closing Argument or Cross-examination .............................103

IX. Federal Cases ...................................................................... 108

1. WHITE-COLLAR CRIMES ........................................................................................... 110

2. MISCONDUCT BY PROSECUTORS ........................................................................... 112

X. Discipline ............................................................................. 115

1. IN GENERAL ............................................................................................................... 115

2. DISCIPLINE BY CATEGORY OF GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL ..................................... 119