Medicaid Coverage of

Medication-Assisted

Treatment for Alcohol

and Opioid Use

Disorders and of

Medication

for the Reversal of

Opioid Overdose

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE ii

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA) by IBM® Watson Health™ as subcontractor to the National Council for Behavioral

Health under Contract #HHSS283201200031I/HHSS28342002T with SAMHSA, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Mitchell Berger served as the Government

Project Officer and Kaitlin Abell as the Contracting Officer Representative.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the author and do not

necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. The listing of

nonfederal resource is not all inclusive, and inclusion on the listing does not constitute

endorsement by SAMHSA or HHS.

Public Domain Notice

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied

without permission from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this

publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authority

of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS.

Electronic Access and Copies of Publication

This publication may be downloaded or ordered from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov. Or call

SAMHSA at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726-4727) (English and Español).

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medicaid Coverage of

Medication-Assisted Treatment for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders and of Medication for the

Reversal of Opioid Overdose. HHS Publication No. SMA-18-5093. Rockville, MD: Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018.

Originating Office

Office of Policy, Planning and Innovation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, 5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857. HHS Publication No. SMA-18-5093,

2018. HHS Publication No. SMA-18-5093. Published in 2018.

Nondiscrimination Notice

SAMHSA complies with applicable federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the

basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex. SAMHSA cumple con las leyes

federales de derechos civiles aplicables y no discrimina por motivos de raza, color, nacionalidad.

HHS Publication No. SMA-18-5093

Published in 2018

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE iii

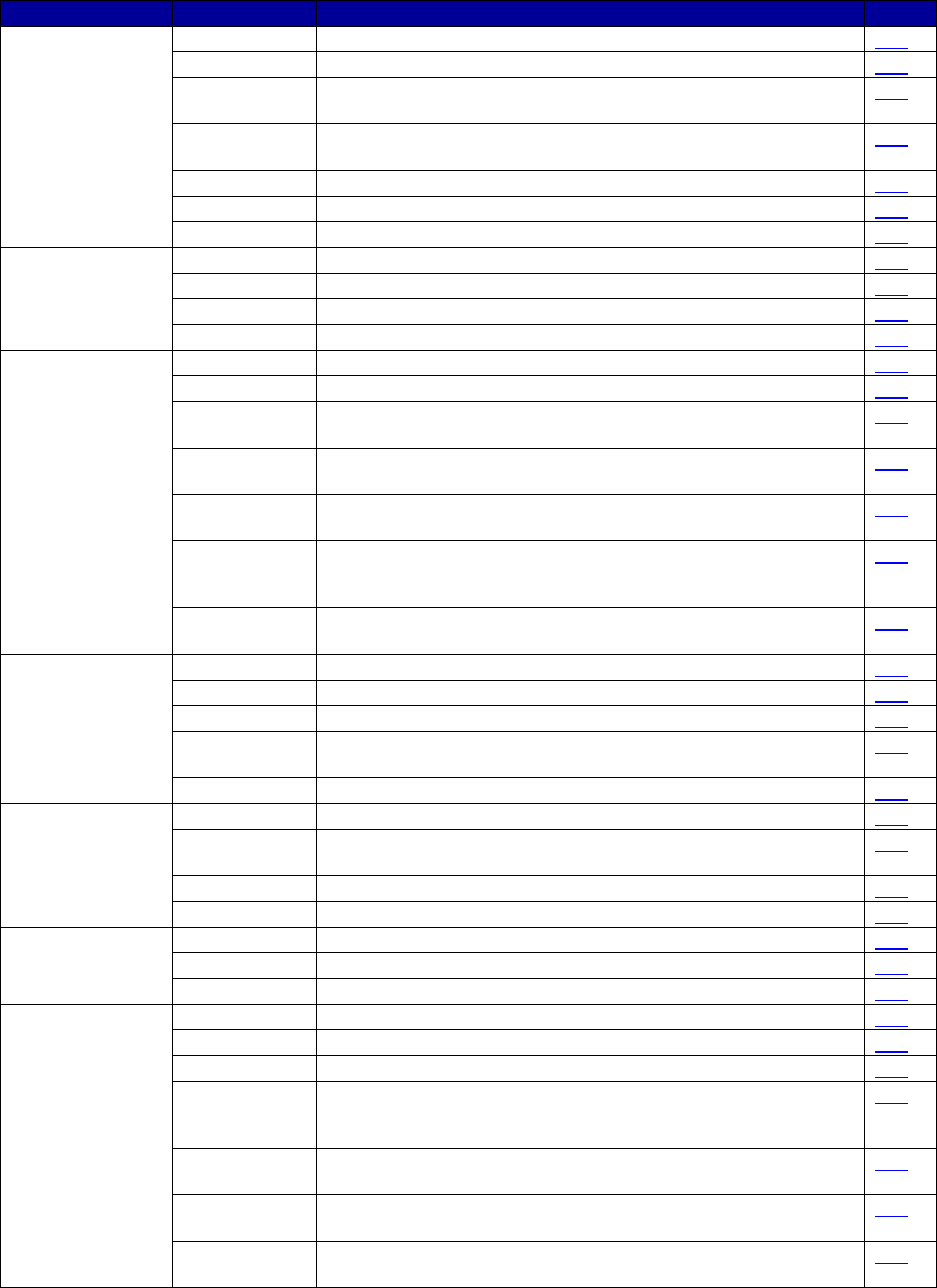

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iii

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1

Background ................................................................................................................................. 1

Study Methods ............................................................................................................................ 1

Key Findings ............................................................................................................................... 2

State Medicaid Program Reimbursement for and Limitations on MAT and Naloxone ......... 2

Key Findings on Innovative Approaches to Financing and Delivering MAT ........................ 4

I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 5

II. State Considerations for Covering Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders ... 7

A. Efficacy of Medications Used to Treat Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders .................... 7

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorders ................................................................................. 8

Medications for Opioid Use Disorders ................................................................................. 10

Medications for Opioid Overdose ......................................................................................... 14

Cost Offset and Cost Effectiveness of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders ... 15

Alcohol Use Disorder Costs.................................................................................................. 15

Opioid Use Disorder Costs ................................................................................................... 16

State and Federal Regulations and Policies Affecting the Prescription and Dispensing of

Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders................................................................. 18

Federal Laws Governing Methadone and Buprenorphine .................................................... 18

Requirements of Parity ......................................................................................................... 19

State Laws and Policies ........................................................................................................ 20

Professional Licensure and Certification .............................................................................. 20

Facility Licensing and Certification...................................................................................... 21

Billing Requirements ............................................................................................................ 21

Data Exchange ...................................................................................................................... 22

Other Policies That May Affect Delivery of MAT ............................................................... 22

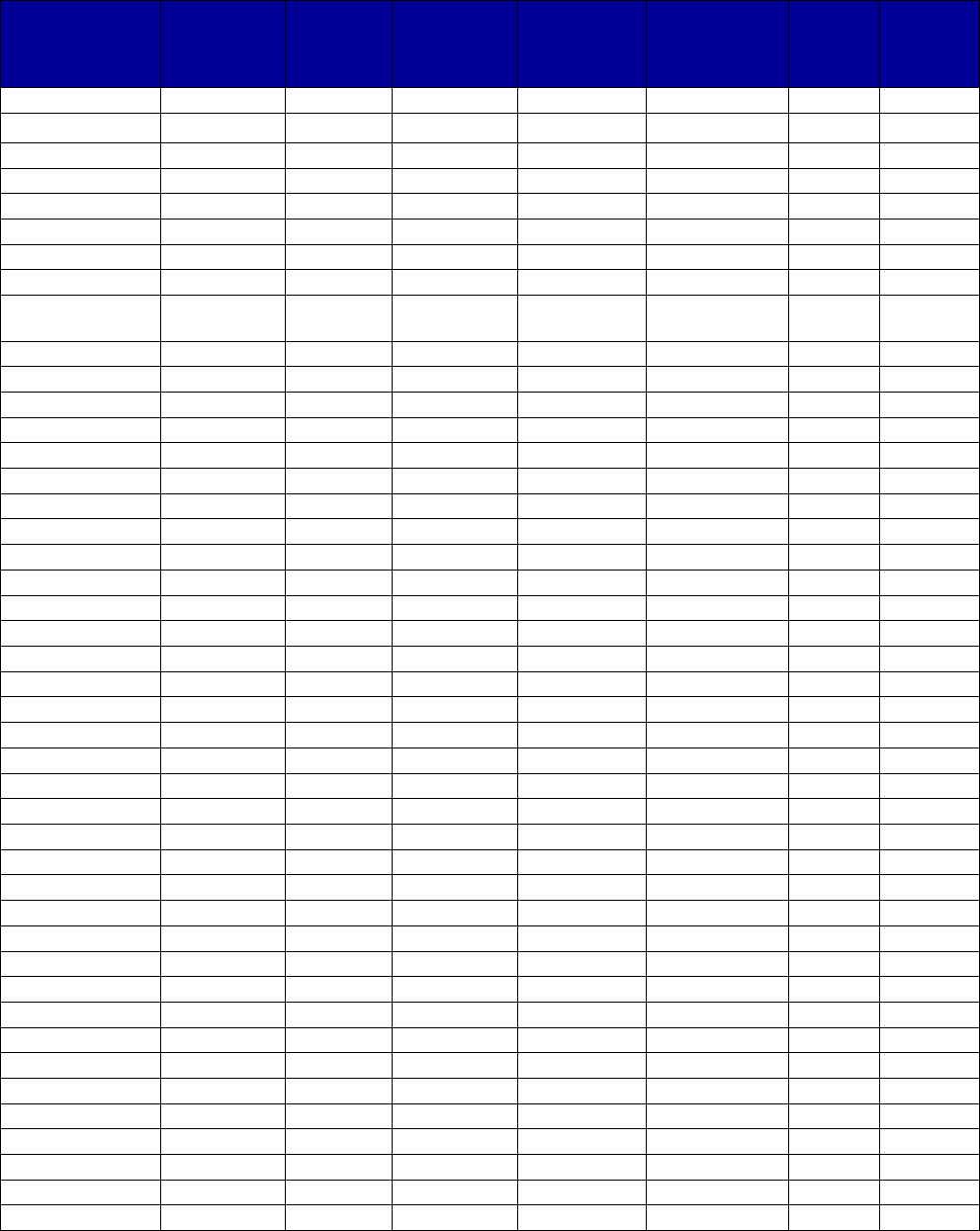

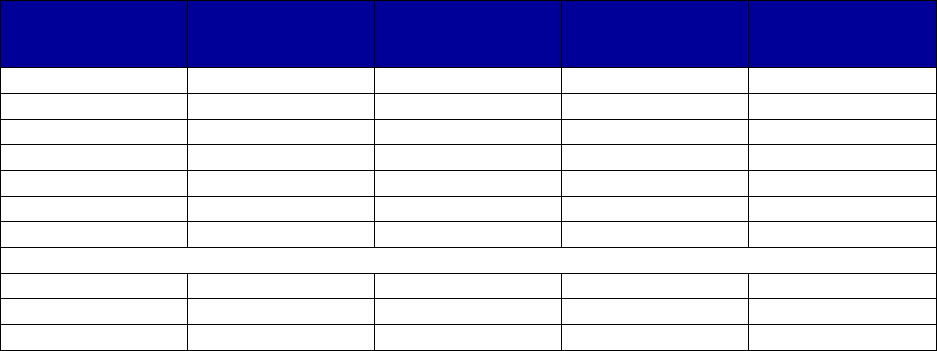

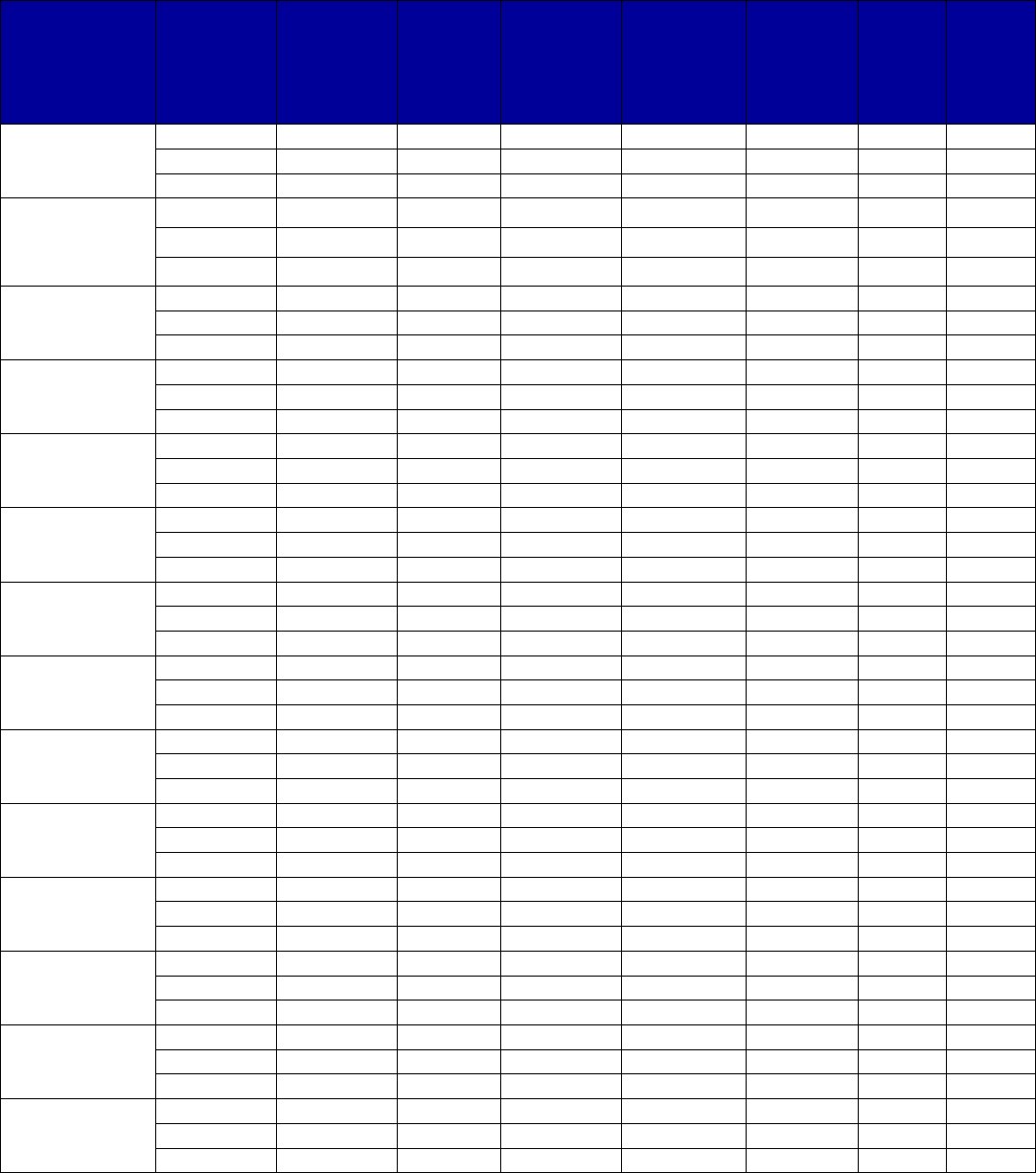

III. Medicaid Coverage of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders ..................... 26

A. Data Sources and Methodology ..................................................................................... 26

Rules for Determining Coverage .......................................................................................... 26

Rules for Determining Preferred Status and Benefit Limitations ......................................... 27

Approach to Analysis of Methadone Coverage.................................................................... 29

Methodology Limitations...................................................................................................... 32

Medicaid Benefit Limits on Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders ................... 32

IV. Innovative MAT Provision, Coverage, and Financing Models ......................................... 41

A. Innovative Models.......................................................................................................... 41

Nurse Care Management Model, Massachusetts .................................................................. 41

Statewide Integration of MAT into SUD Treatment, Missouri ............................................ 43

Flex Care Telemedicine-MAT Pilot Project and Other Innovative MAT Approaches,

Washington ........................................................................................................................... 45

B. Cross-Cutting Best Practices.......................................................................................... 47

V. Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 50

A. Coverage of Medications Used for MAT....................................................................... 50

B. Benefit Design................................................................................................................ 50

C. Other Considerations...................................................................................................... 51

D. Lessons Learned from Innovative Approaches to Financing MAT. .............................. 51

VI. References .......................................................................................................................... 53

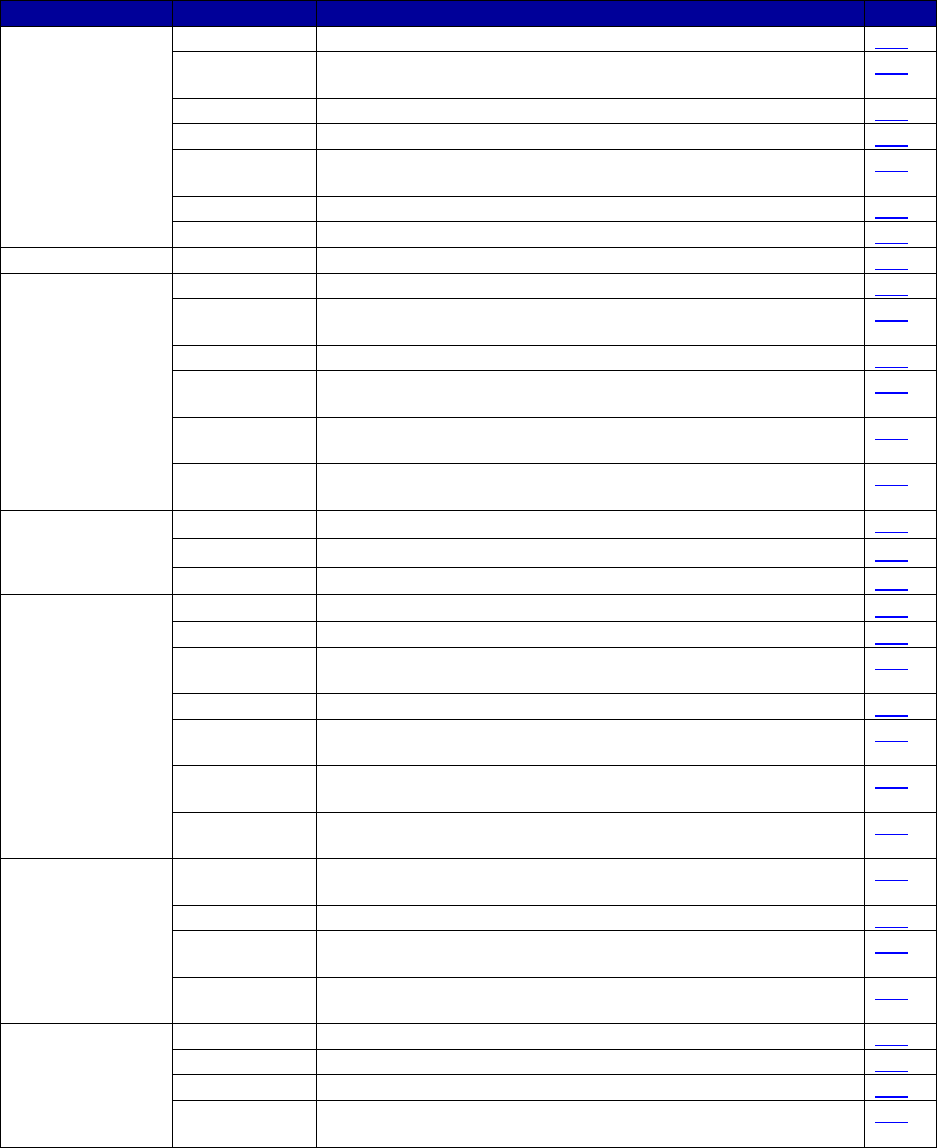

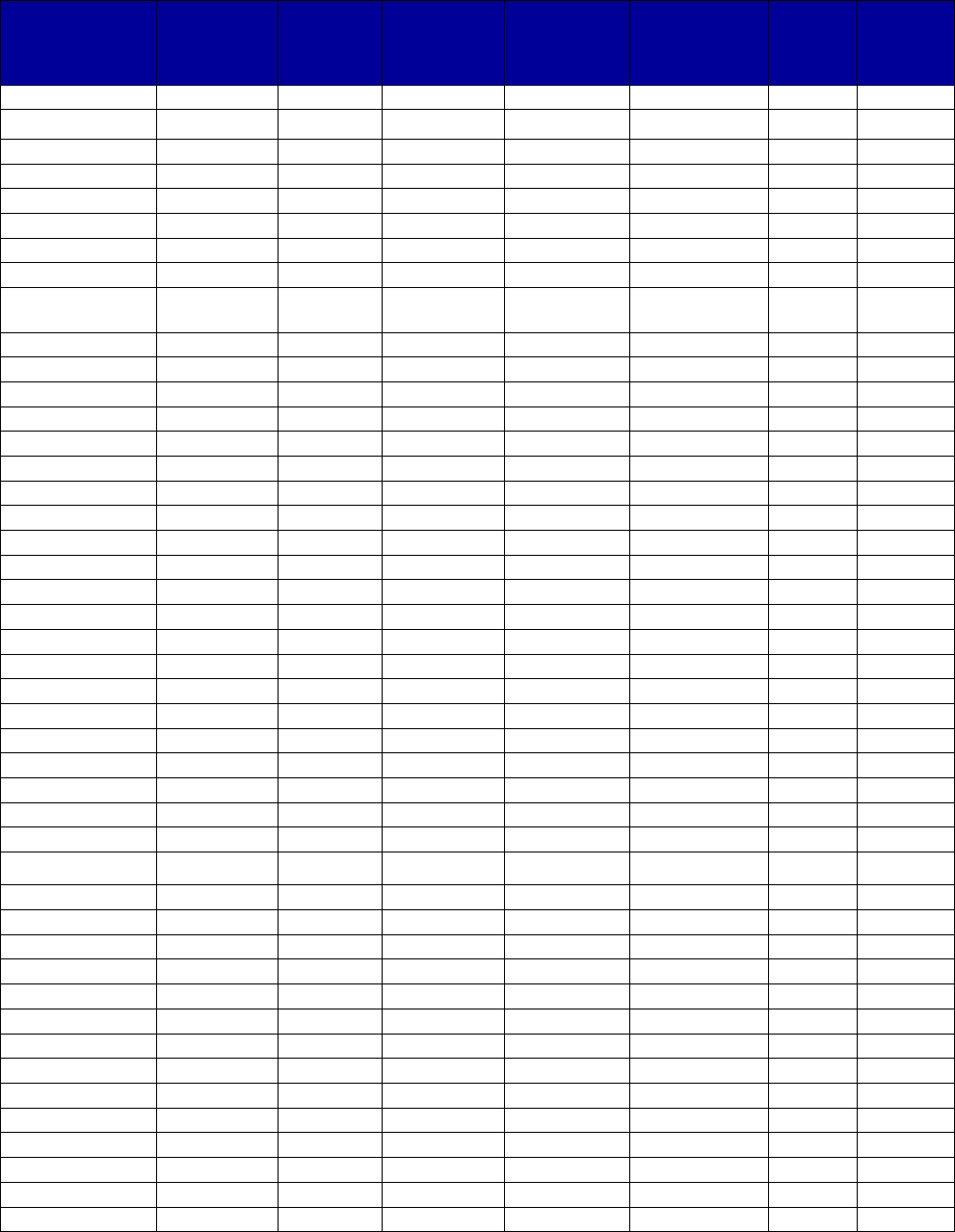

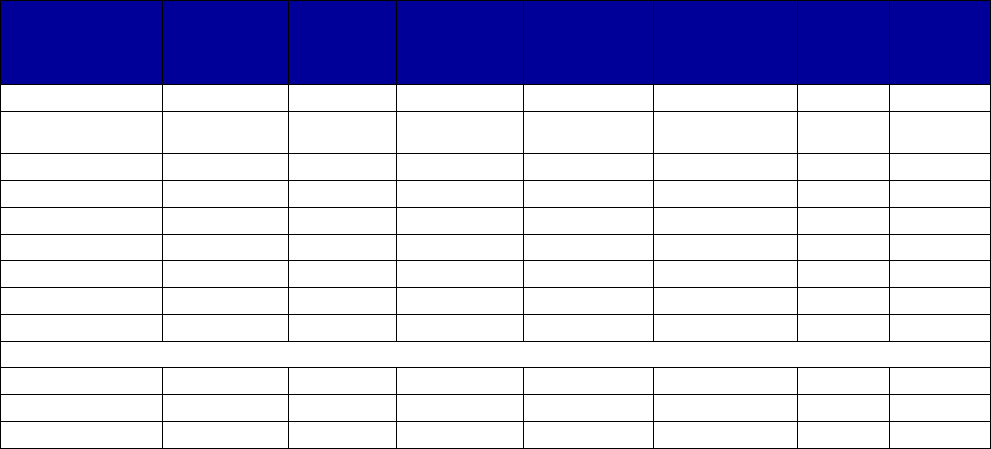

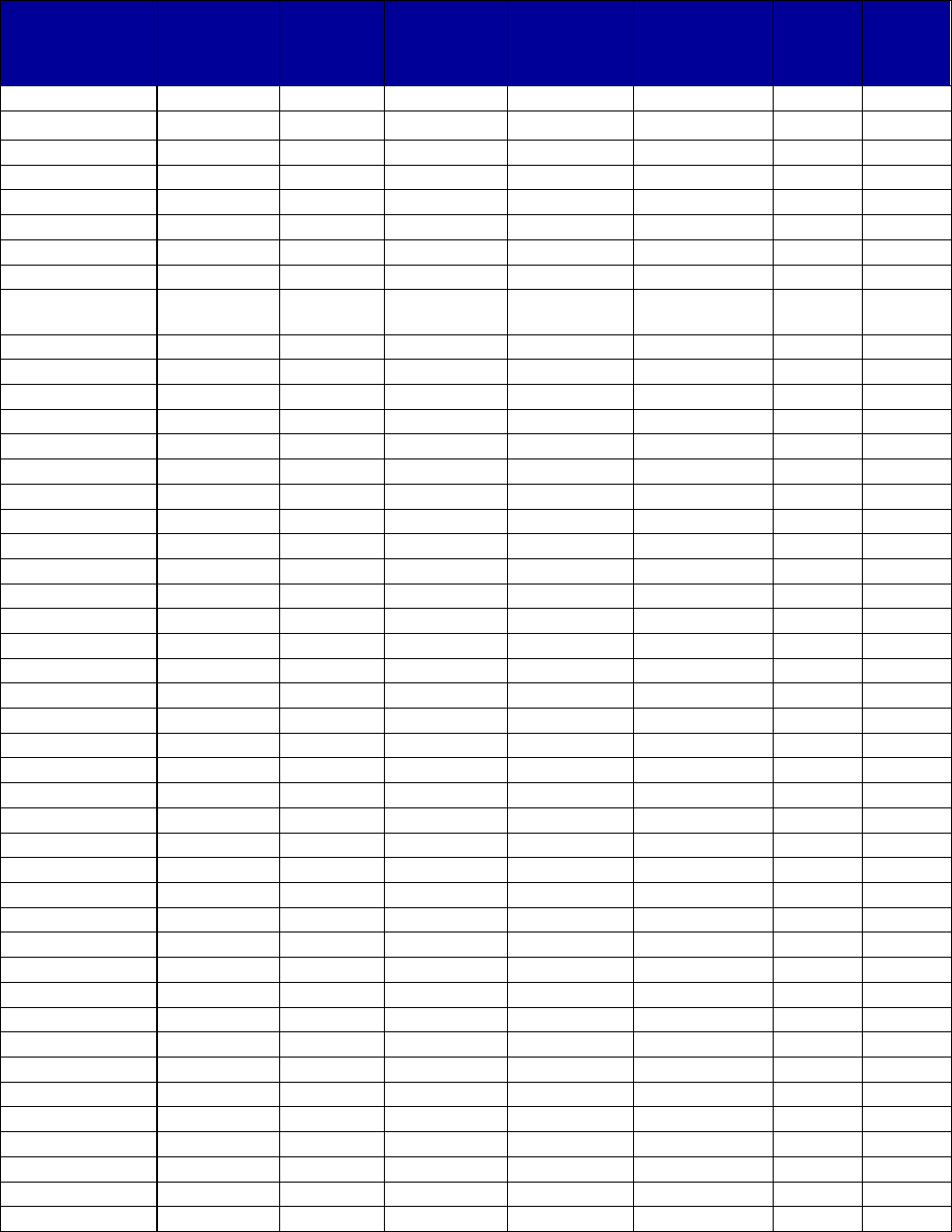

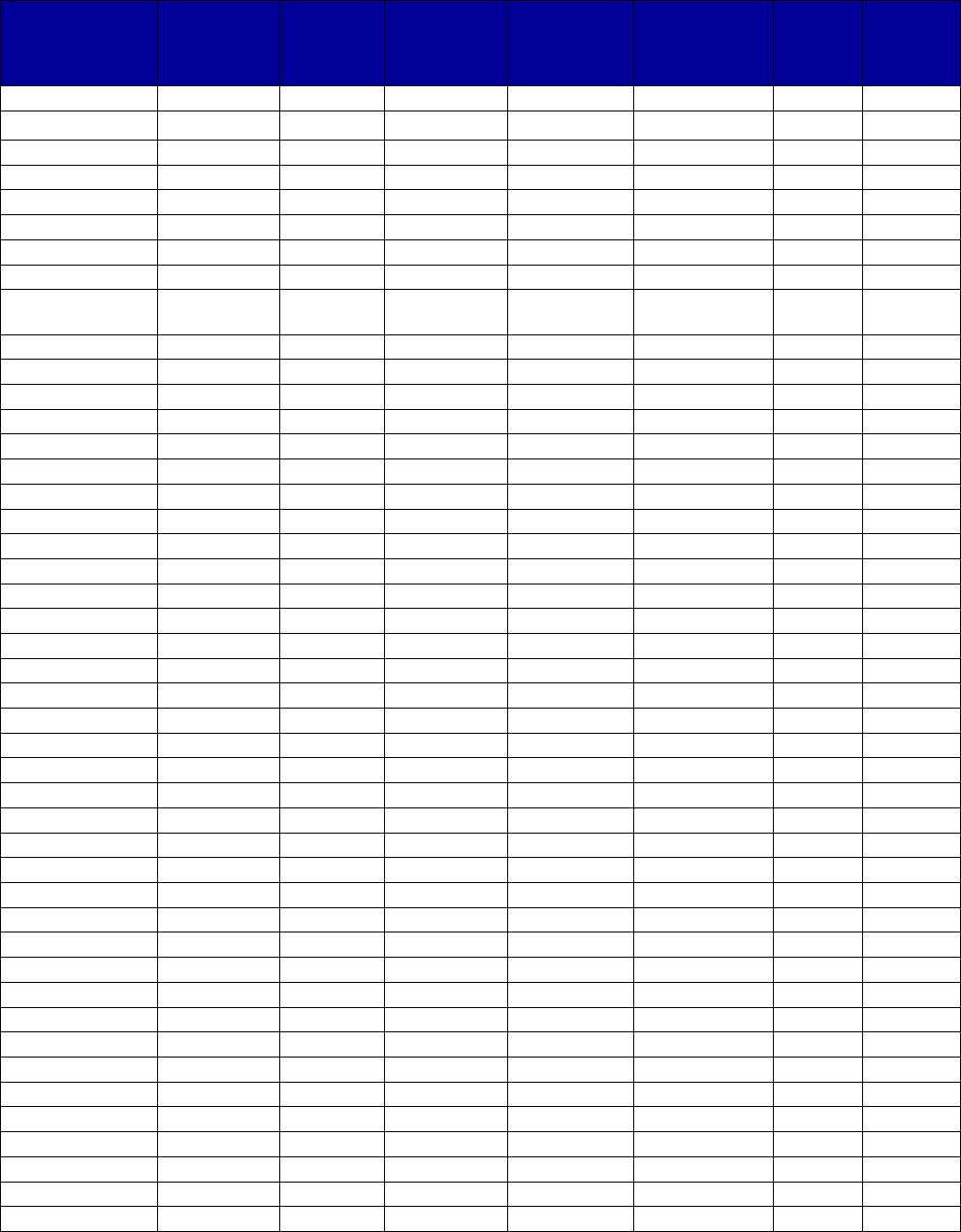

VII. Appendix A. Coverage of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders by State . 69

VIII. Appendix B. Authors and Acknowledgements ................................................................ 113

Authors ................................................................................................................................ 113

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 113

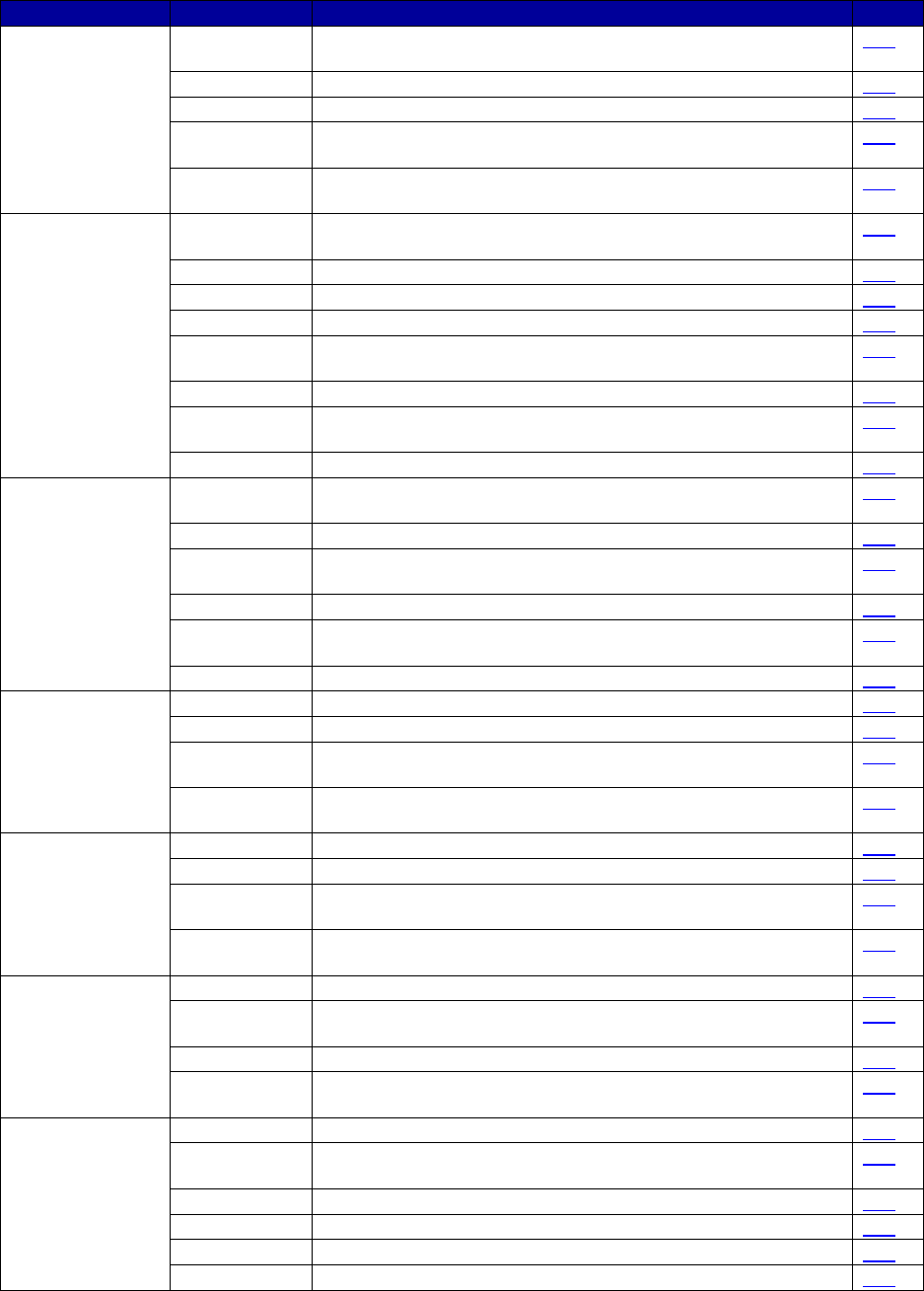

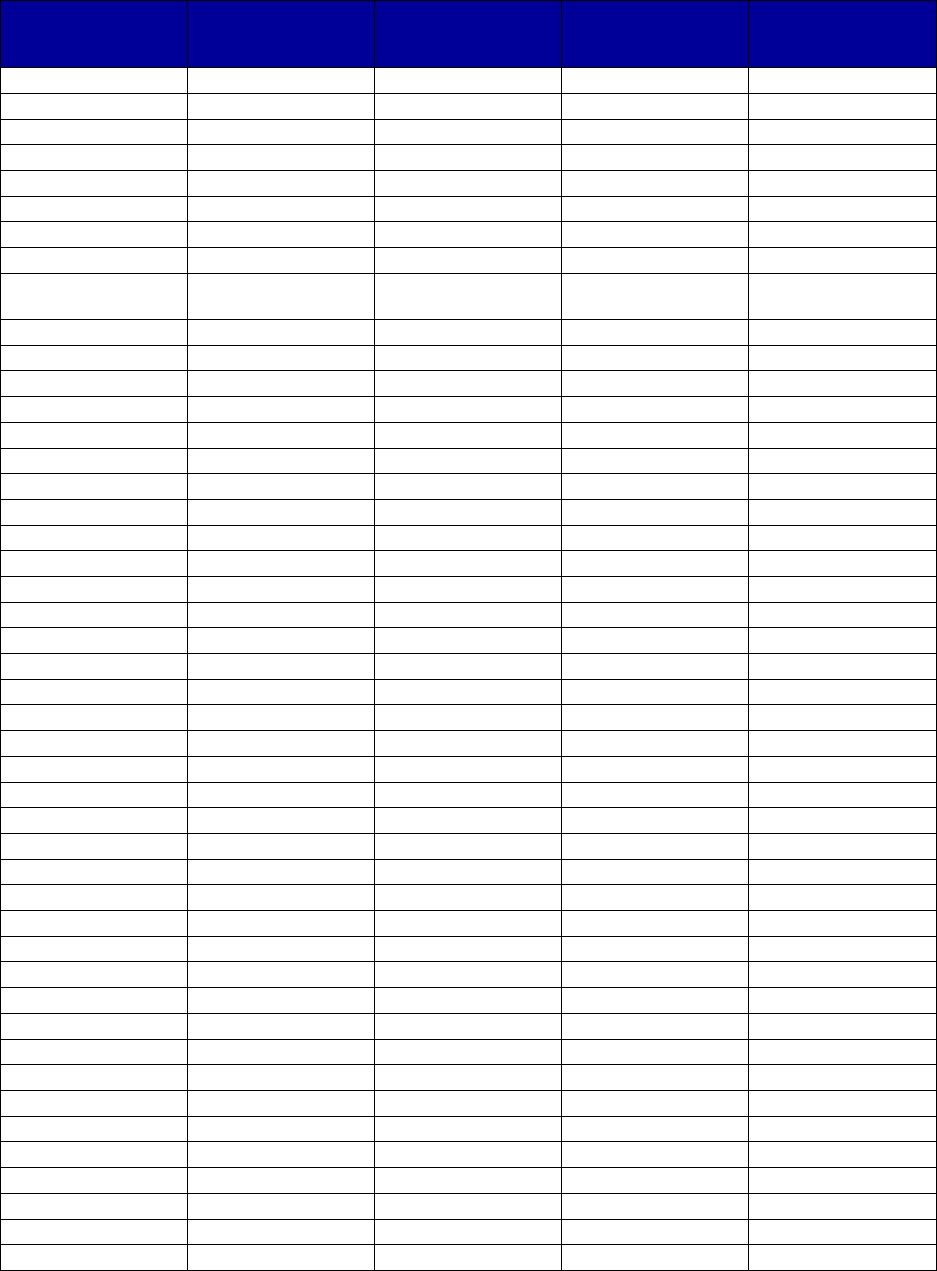

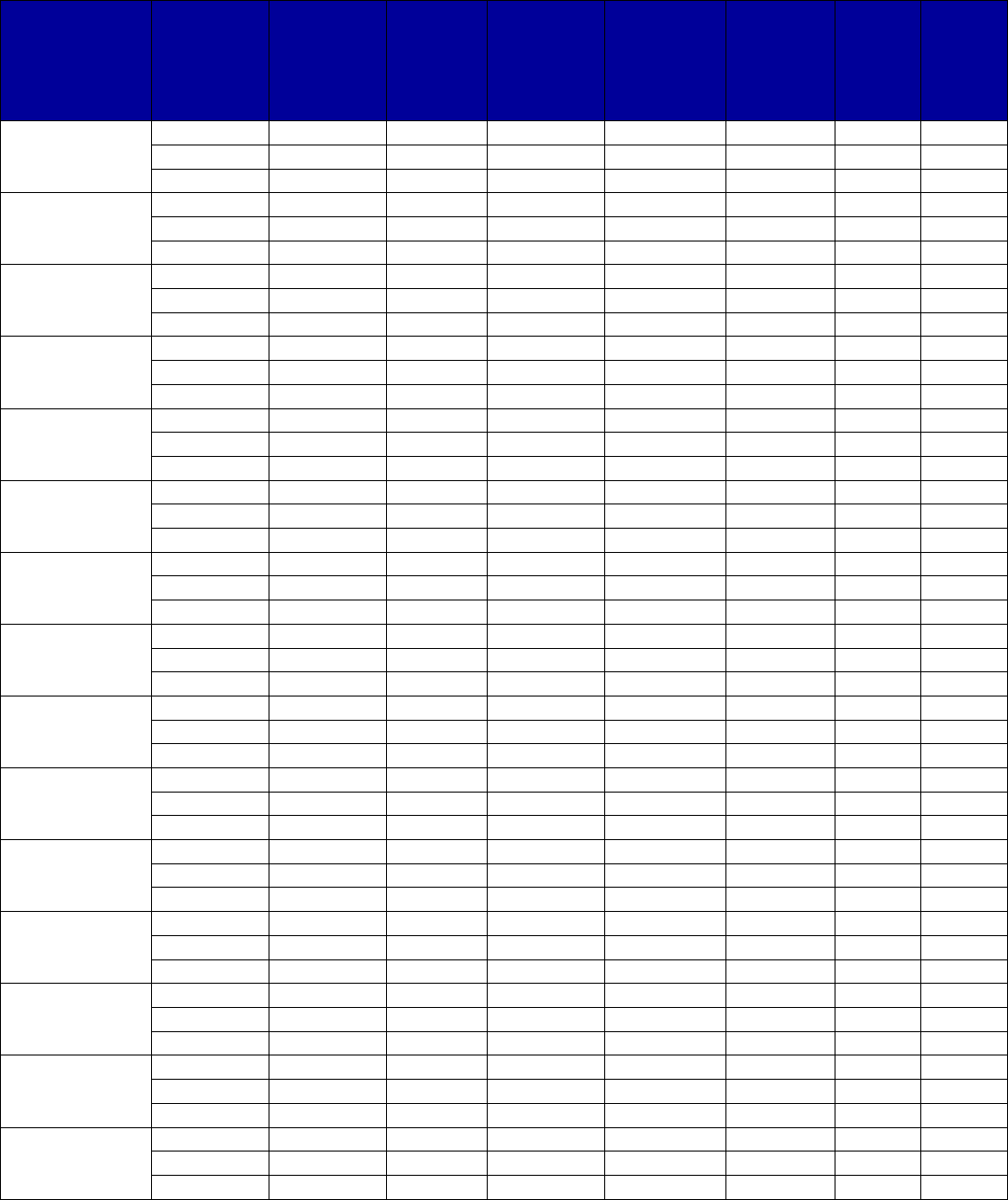

Tables

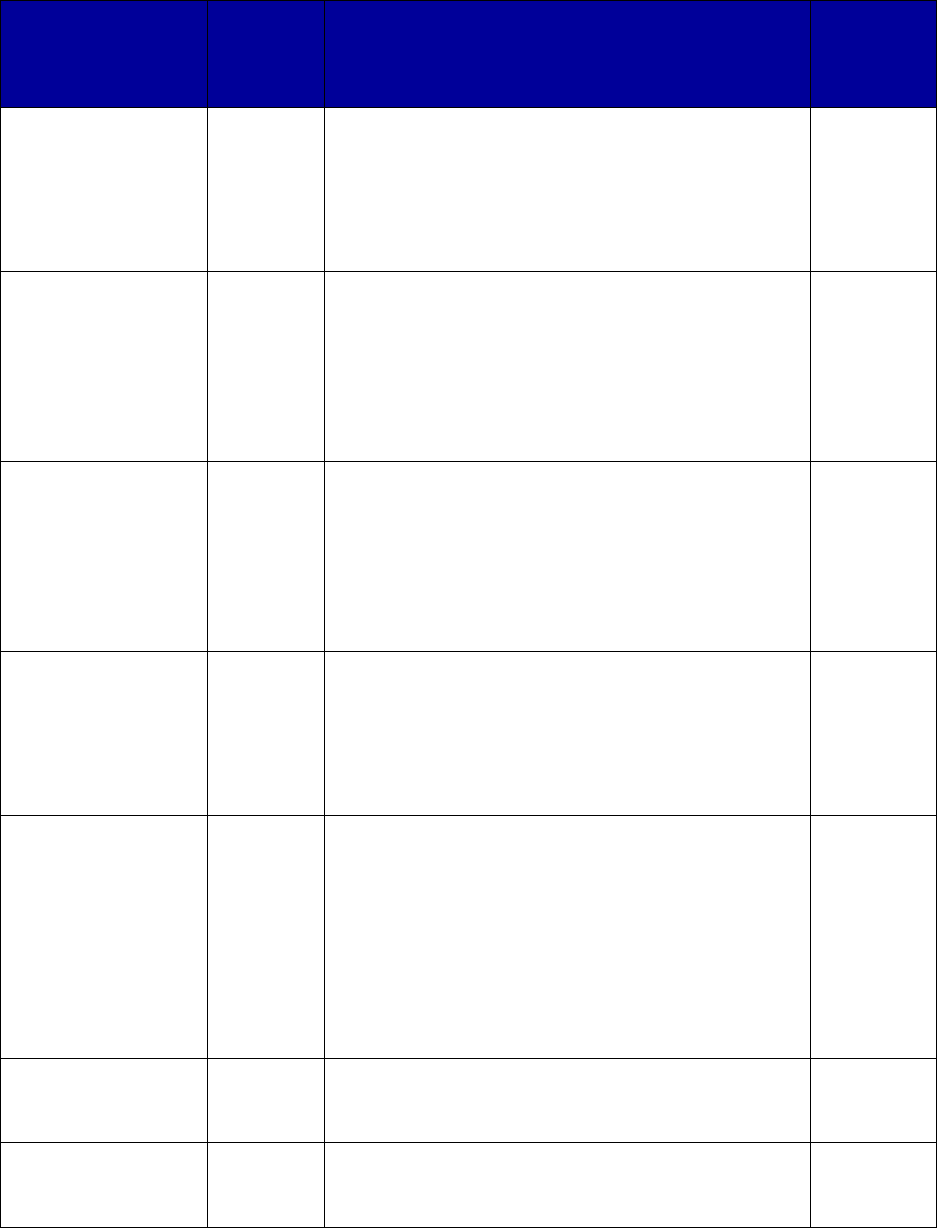

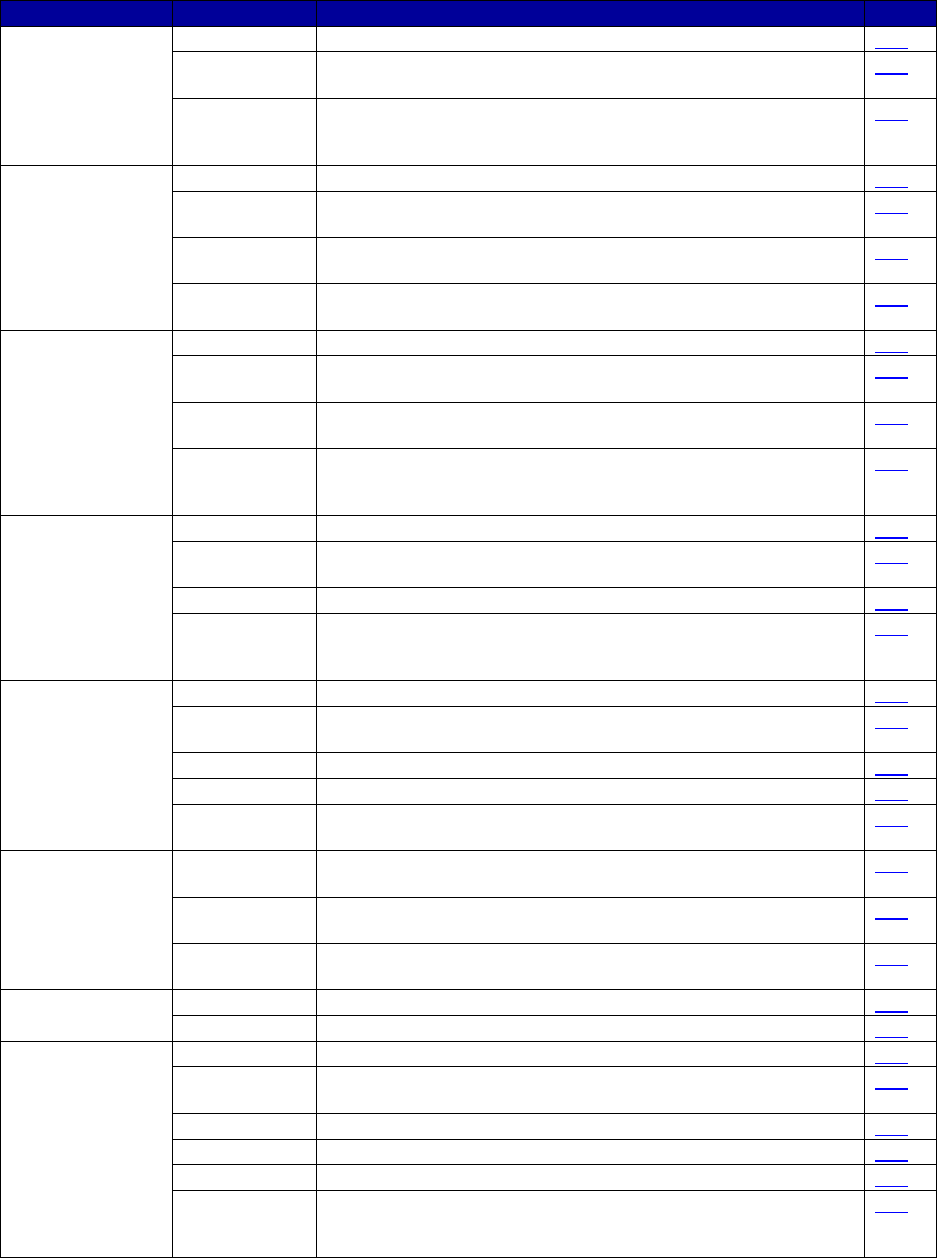

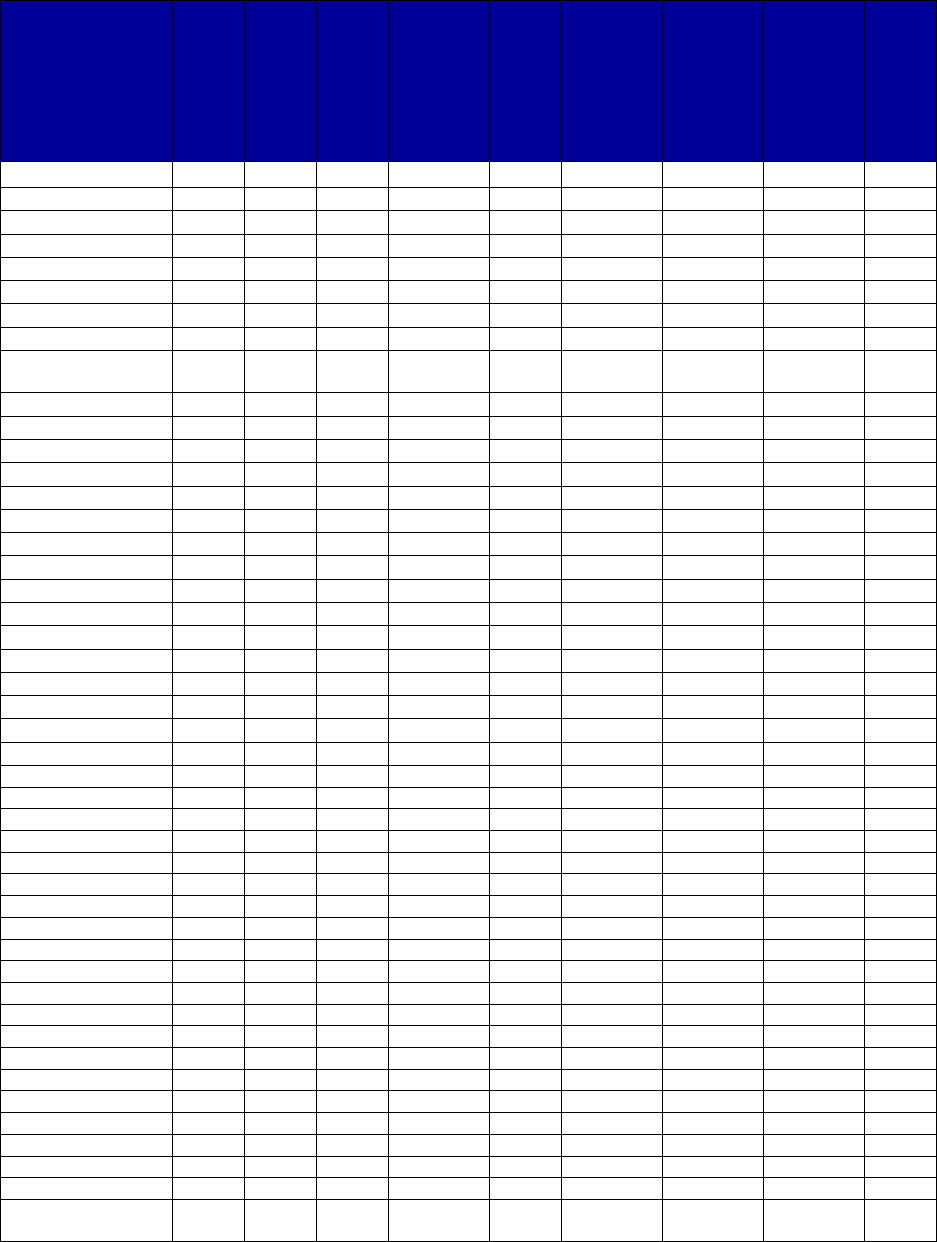

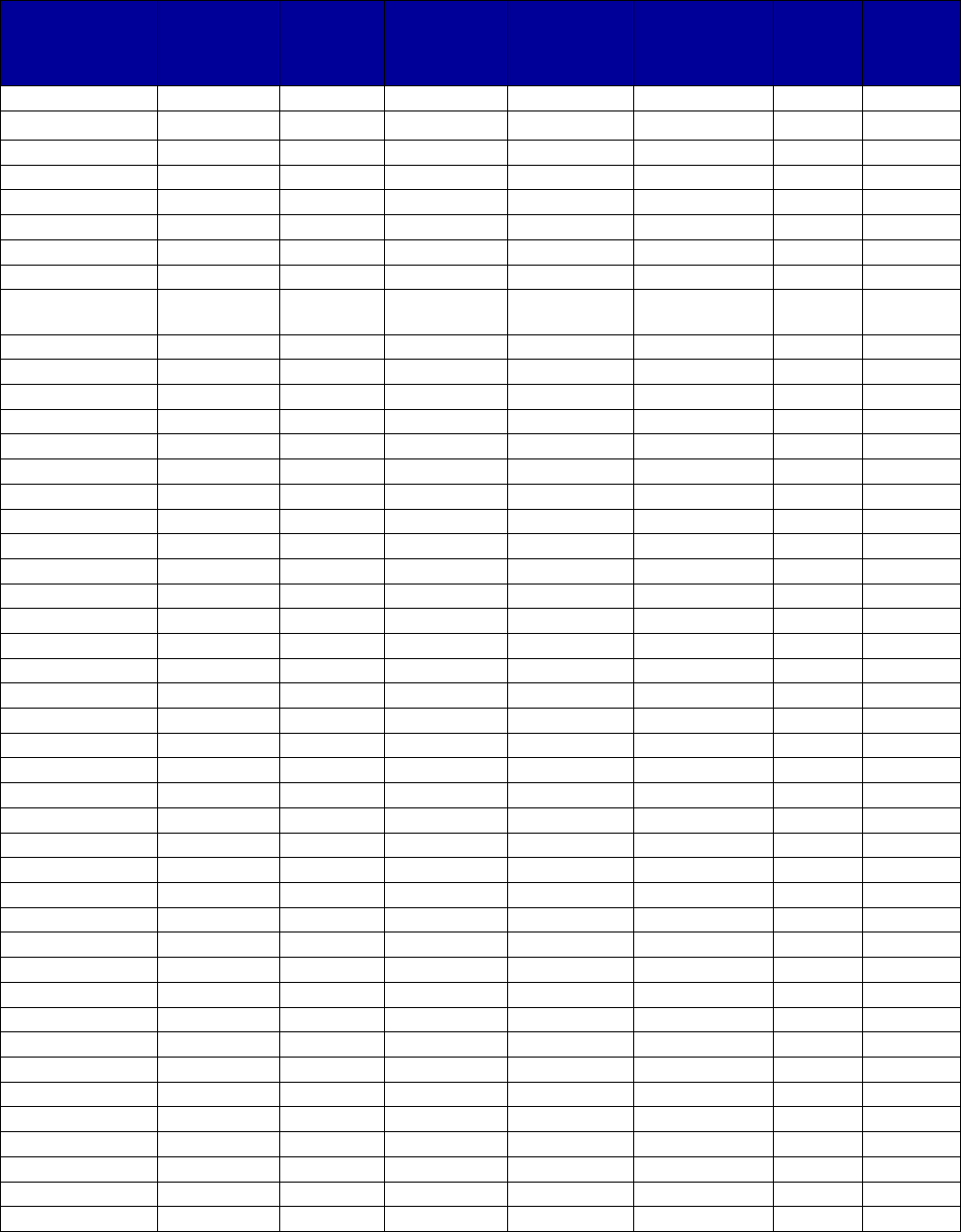

Table 1. Medications Used to Treat Alcohol Use Disorders .......................................................... 8

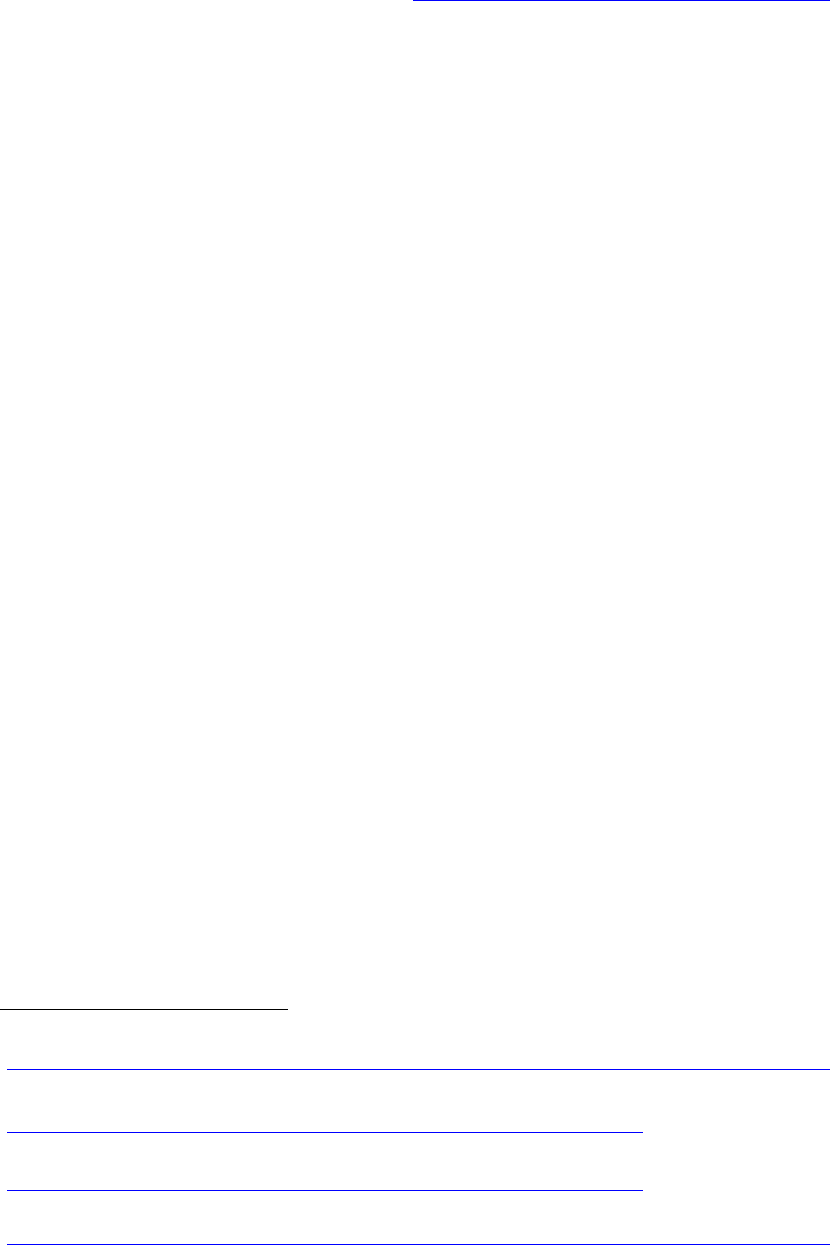

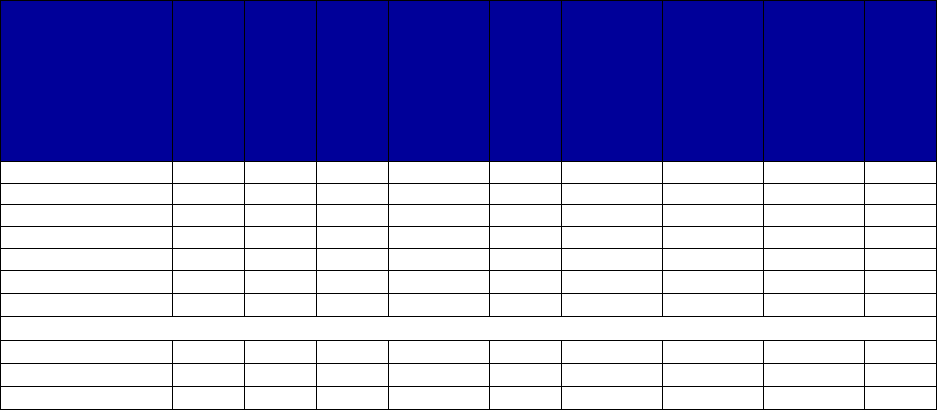

Table 2. Medications Used to Treat Opioid Use Disorders .......................................................... 11

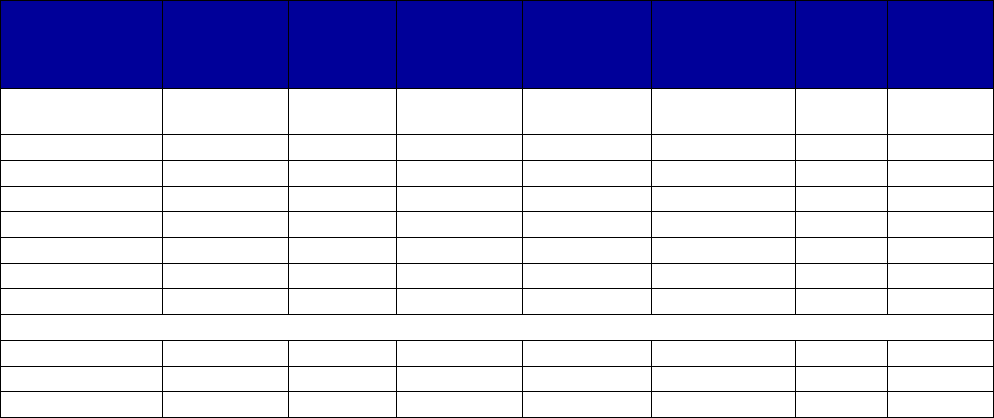

Table 3. Federal Prescribing Regulations for Medications Used to Treat Alcohol and Opioid Use

Disorders or to Reverse Opioid Overdose .................................................................................... 19

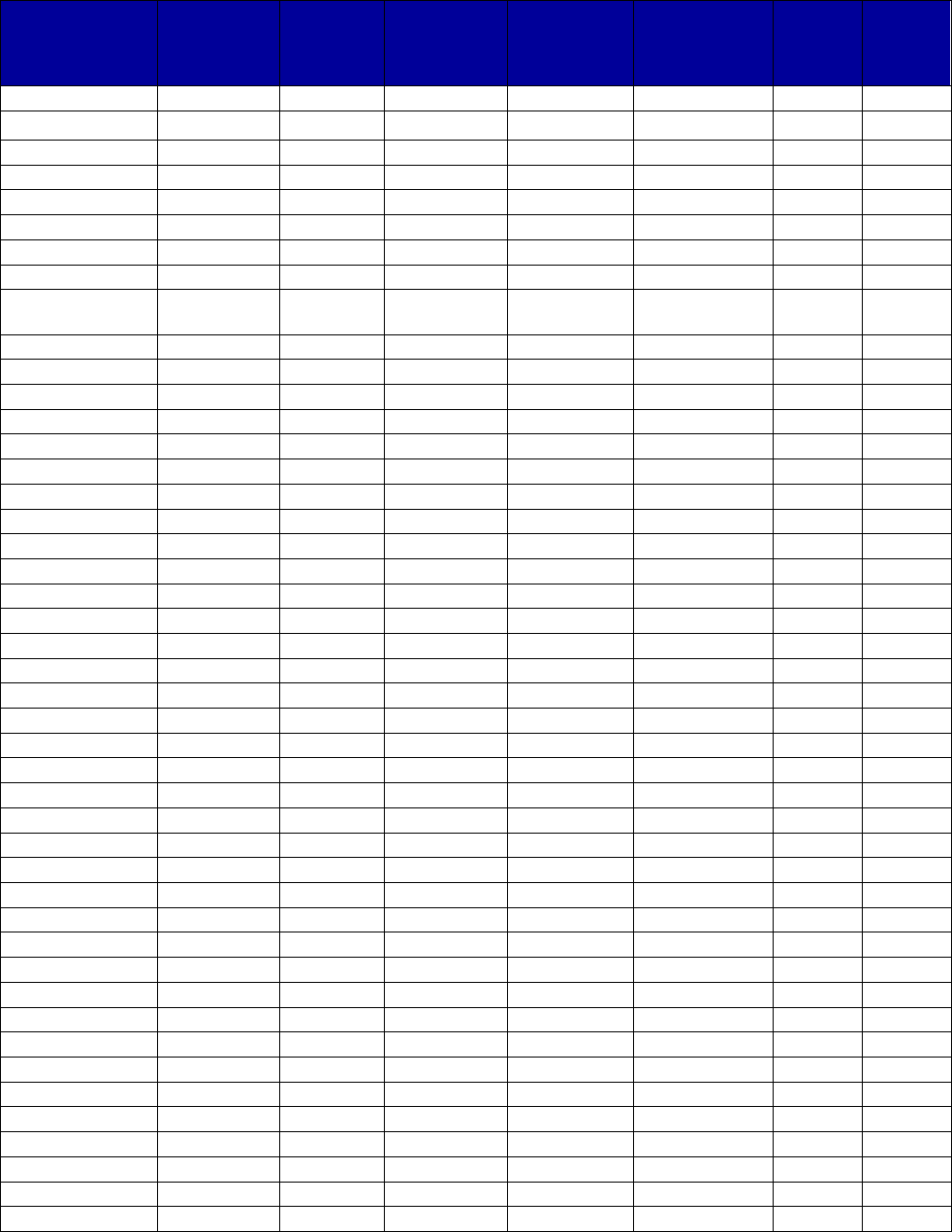

Figures

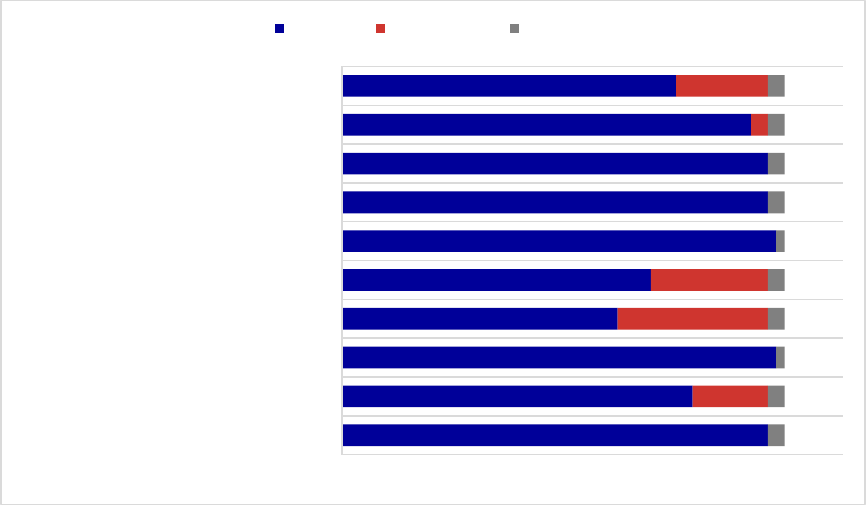

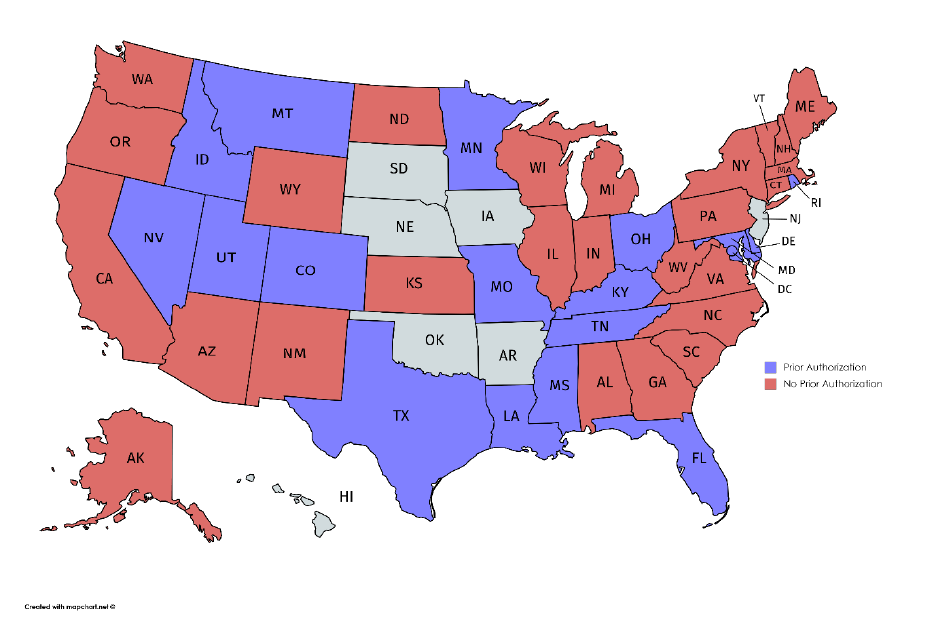

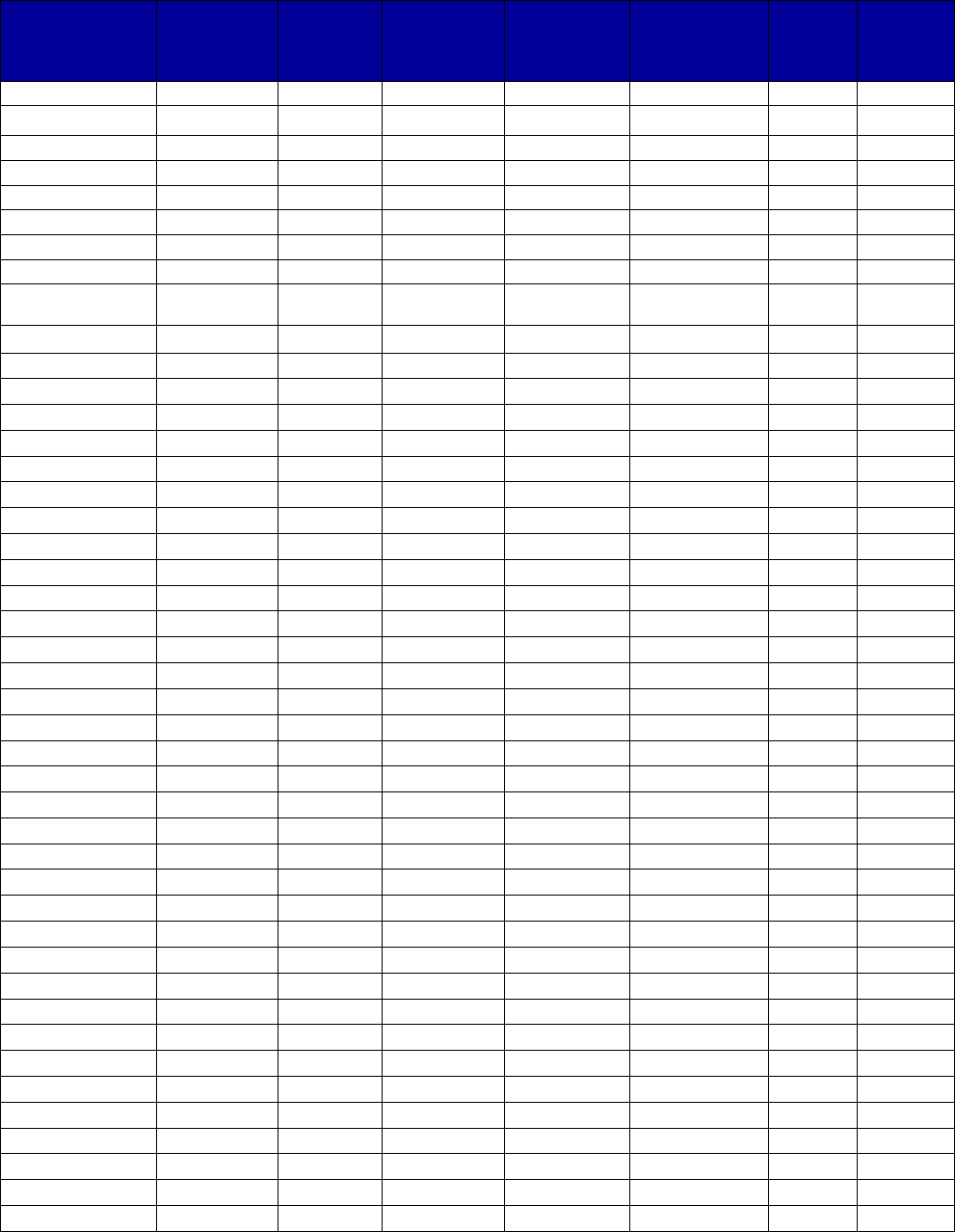

Figure 1. Medicaid Coverage of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders or to

Reverse Opioid Overdose, 2018

a

.................................................................................................. 34

Figure 2. Preferred Status of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders or to Reverse

Opioid Overdose, 2018

a

................................................................................................................ 35

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE iv

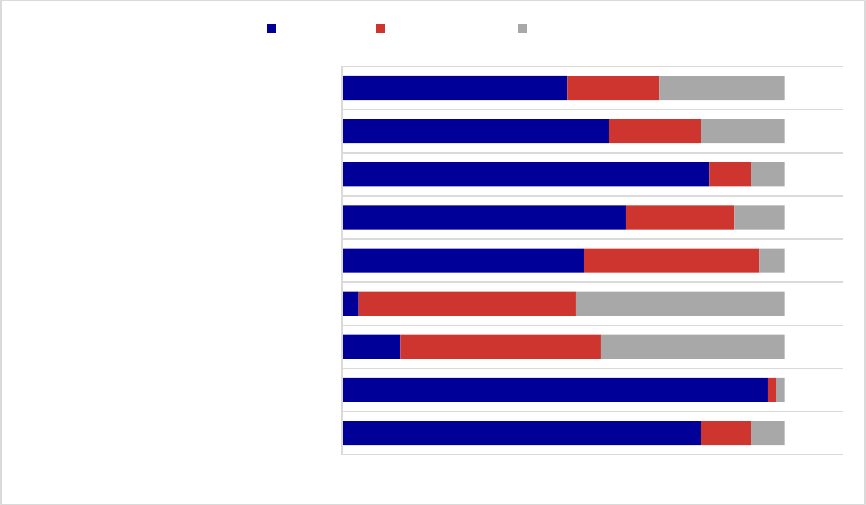

Figure 3. Prior Authorization Requirements for Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use

Disorders or to Reverse Opioid Overdose, 2018

a

......................................................................... 36

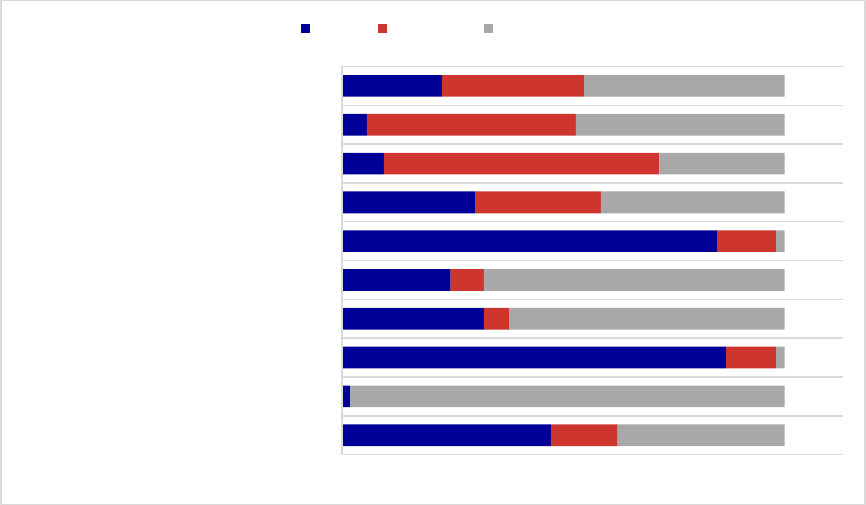

Figure 4. Prior Authorization Requirements for Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone, 2018

a

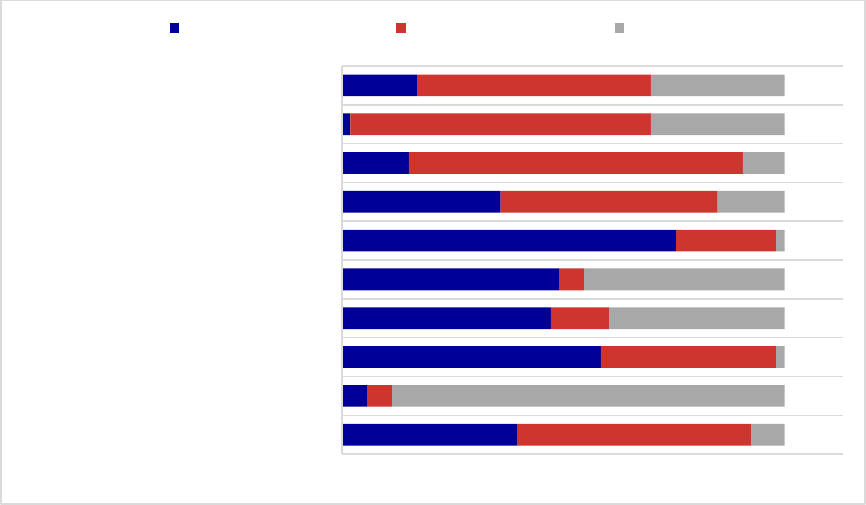

Figure 5. Quantity or Dosing Limit Requirements for Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use

....................................................................................................................................................... 37

Disorders or to Reverse Opioid Overdose, 2018

a

......................................................................... 38

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE v

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

1

Executive Summary

This report presents summary information on Medicaid coverage and financing of medications to

treat alcohol and opioid use disorders. Medicaid serves over 72 million adult and child

beneficiaries annually (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2017a). An estimated

12 percent of adults over 18 years of age and 6 percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years in

Medicaid have a substance use disorder (SUD)

1

(CMS, 2014, 2015). Given the important role

that medications can play in treating these disorders, it is critical that Medicaid programs develop

clinically effective and cost-effective delivery and financing approaches to providing these

medications to beneficiaries. The present report is intended to serve as a resource guide for those

efforts.

Background

Excessive alcohol consumption and/or the use of illicit drugs have been clearly linked to adverse

health and social outcomes (Bouchery, Harwood, Sacks, Simon, & Brewer, 2011; Devlin &

Henry, 2008; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2012a). There are an estimated 88,000 deaths

each year due to the use of alcohol (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013), and drug

overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with more than 72,000

lethal drug overdoses estimated in 2017 and 63,632 in 2016 (National Institute on Drug Abuse,

2018). Of the 63,632 drug overdoses in 2016, 42,249 deaths involved an opioid and, out of those,

15,469 involved heroin (Seth, Scholl, Rudd, & Bacon, CDC MMWR, 2018).

Fortunately, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved effective medications

for treating alcohol and opioid use disorders. These medications include:

• disulfiram and acamprosate for treatment of alcohol dependence;

• methadone, buprenorphine (including oral, subdermal and injectable extended-release

formulations), and buprenorphine-naloxone (including oral, buccal, and sublingual) for

treatment of opioid dependence; and

• naltrexone (oral and an injectable extended-release formulation) for treatment of alcohol

or opioid dependence.

In addition, naloxone is an effective medication used to reverse opioid overdose.

Study Methods

The research team retrieved the most recent pharmacy and behavioral health documents from

state Medicaid agency websites during the second and third quarters of 2018. Searches were

conducted for information related to Medicaid pharmaceutical coverage of and benefit design for

medication-assisted treatment (MAT), including selected Medicaid managed care plans, if

1

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5

th

ed. (DSM-5), an SUD is characterized

by a problematic pattern of using a substance that results in impairment in daily life or noticeable stress.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

2

available. Internet queries sought documents providing information on formularies, Preferred

Drug Lists (PDLs), prior authorization, psychosocial treatment requirements, quantity limits, and

other pharmacy benefit limitations. Where ambiguity remained, the research team accessed

online drug search tools such as Epocrates® (https://online.epocrates.com/rxmain), which

provided additional information that allowed us to pursue the subject further using other

documents. Medications may be covered by state Medicaid programs without being listed on an

easily accessible formulary; therefore, when no other evidence of coverage was found in the

Medicaid or other documents, a final determination of whether Medicaid coverage existed was

made by searching the 2018 Medicaid State Drug Utilization Data (CMS, n.d.).

Key Findings

State Medicaid Program Reimbursement for and Limitations on MAT and Naloxone

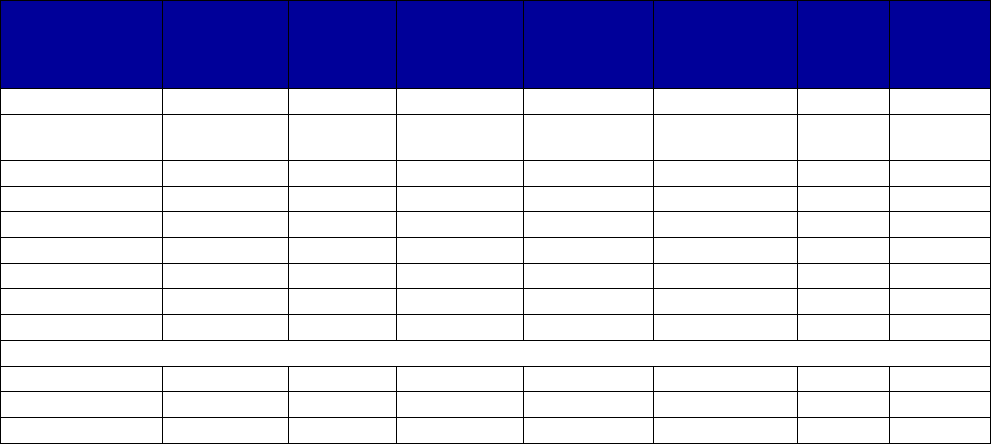

All states reimburse for some form of medications for MAT. A review of Medicaid policies

and data revealed that all states reimburse some form of buprenorphine, buprenorphine-

naloxone, oral naltrexone, and extended-release naltrexone and that most states cover disulfiram

and acamprosate. All states also reimburse for some form of naloxone, the opioid overdose

reversal medication. Only 42 state Medicaid programs, however, reimburse for methadone as

MAT (in contrast to reimbursing for the use of methadone to treat pain and other conditions),

and fewer than 70 percent of states reimburse for implanted or extended-release injectable

buprenorphine.

Even if state Medicaid agencies reimburse for specific medications, they may impose

certain constraints, or benefit design limits, on obtaining the medication. State Medicaid

agencies typically rely on a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee or equivalent entity to

determine whether to reimburse for a medication and whether it will be assigned preferred or

nonpreferred status, a subject addressed in greater detail below and in Section I of this report.

These committees establish PDLs, which typically list the first-choice medication(s) preferred

for a given condition for Medicaid patients. State Medicaid agencies also may establish other

benefit design limits that must be satisfied in order to obtain reimbursement for the medication.

These limits may include quantity or dosing limits, prior authorization, requirements for

psychosocial treatment, and step therapy, the latter three of which are known as “nonquantitative

treatment limitations,” or NQTLs. Each of these benefit design features are addressed in greater

detail below and in Section I of this report.

Reimbursement of medications as MAT does not mean that they all have preferred status

within state Medicaid programs. Reimbursement may be available for a medication even if

the medication does not have preferred status; however, if a medication does not have preferred

status, the prescriber usually must obtain permission from the member’s pharmacy benefit plan

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

3

before the product can

be reimbursed. In some

instances, a drug still

may require

authorization even if it

has a preferred status.

Preferred status of a

drug also can vary

between fee-for-service

and managed care

plans within a state’s

Medicaid program.

The majority of state

Medicaid programs

assign preferred status

to all of the MAT

medications and

naloxone, with the

exceptions of the extended-release versions of buprenorphine. In addition, we concluded that at

least one formulation of naloxone, which is used to reverse opioid overdose, was covered with

preferred status in 43 state Medicaid programs.

State Medicaid programs routinely use pharmacy benefit management requirements, such

as prior authorization, to contain expenditures and encourage the proper use of

medications, including for the treatment of alcohol and opioid disorders. Research on the

use of prior authorization requirements with psychiatric medications has revealed that prior

authorization can reduce medication expenditures. However, these requirements also can have

the unintended consequence of preventing timely access to treatment. Potential barriers to access

may be reduced as payers and providers move from a paper-based prior authorization process to

an electronic, real-time, standardized process. An electronic process may integrate better into

providers’ workflow and may reduce the time that providers and patients must wait to secure

authorization. Among the medications reviewed, prior authorization was required most

commonly for buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone, in 40 and 31 states, respectively.

Most prior authorization requirements for buprenorphine monotherapy exist because of its

potential for abuse, and many include restrictions limiting it to use by pregnant women and in

other limited applications. Prior authorization for extended-release injectable naltrexone is

required in 19 states, likely because it is not available in generic form, making it more expensive,

and because patients must abstain from opioids for a minimum of 7 days prior to receiving the

injection. Extended-release forms of buprenorphine also require prior authorization in

approximately half of all states; they also are brand drugs and require that the patient be

stabilized on other medication before their use. Relatively few states require authorization for the

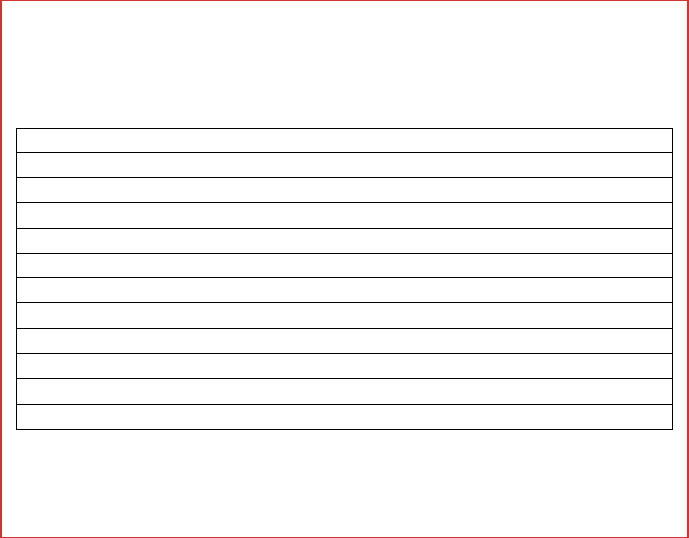

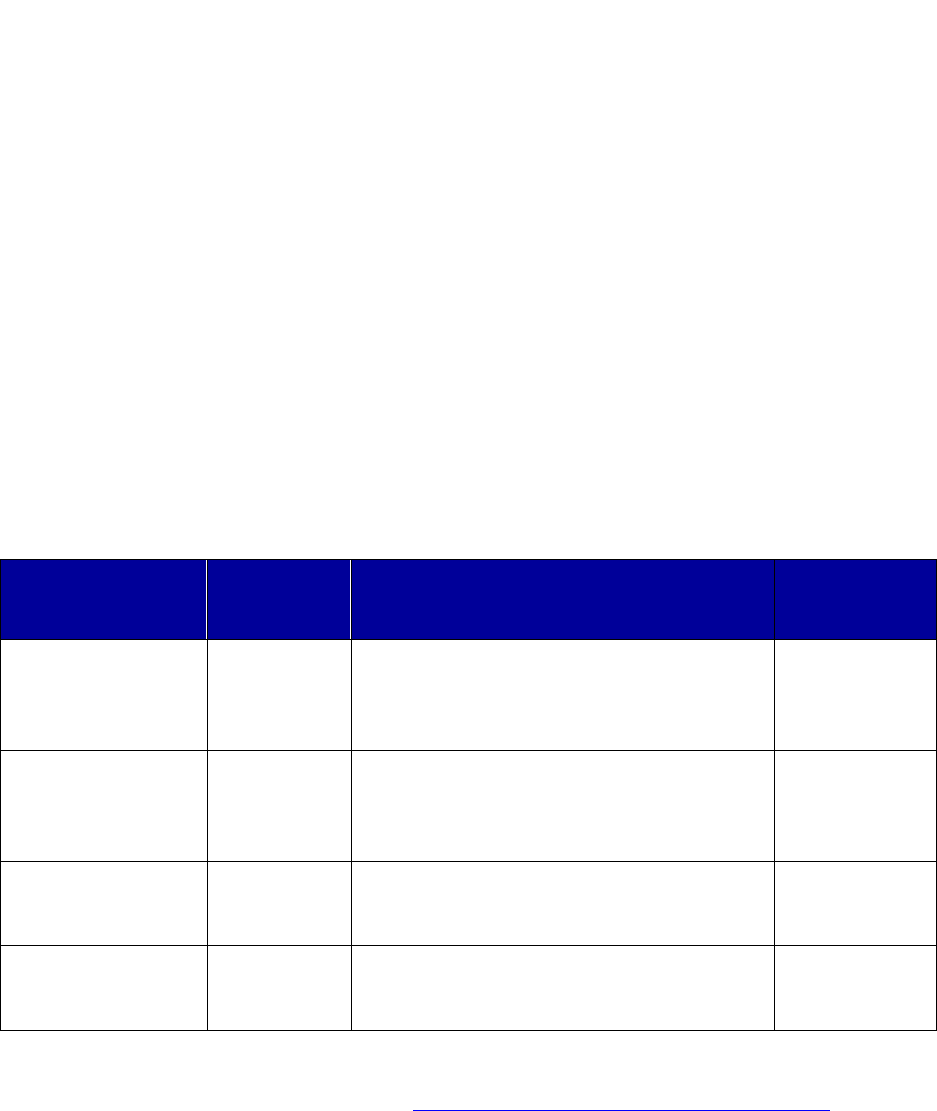

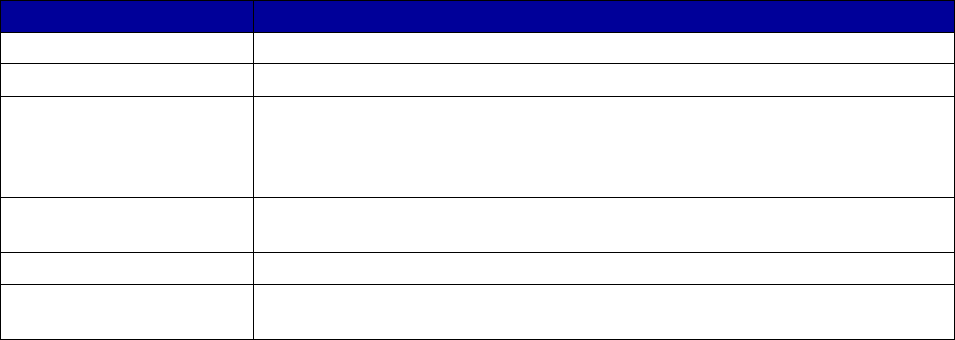

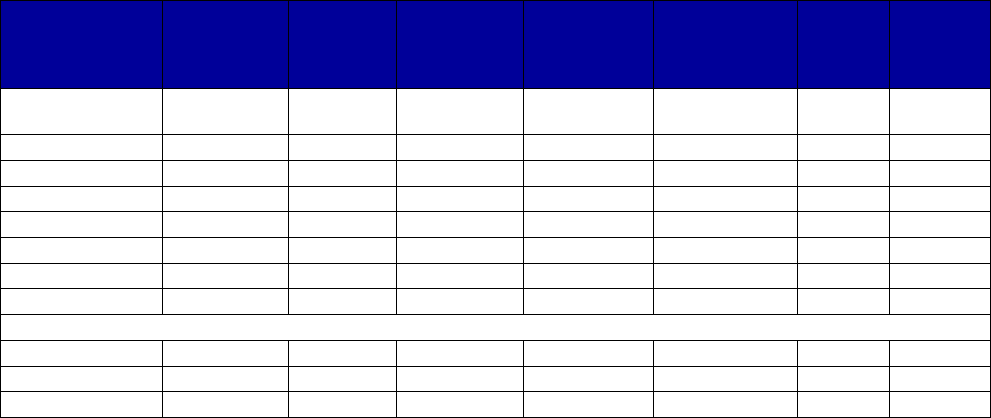

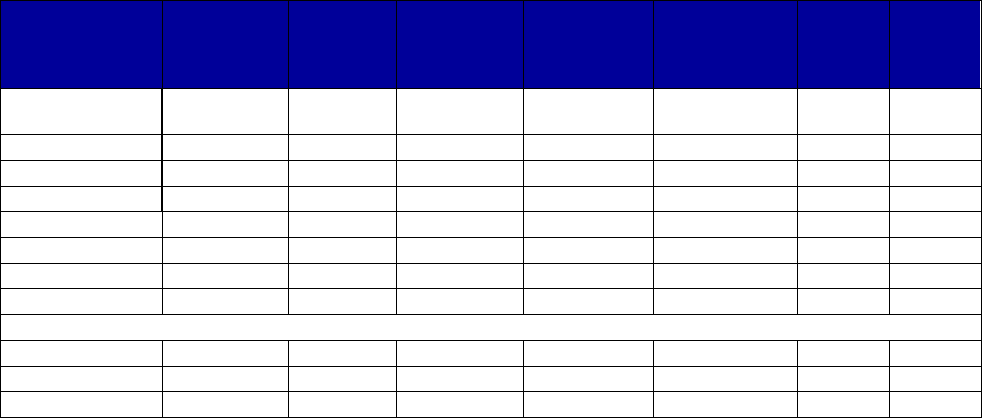

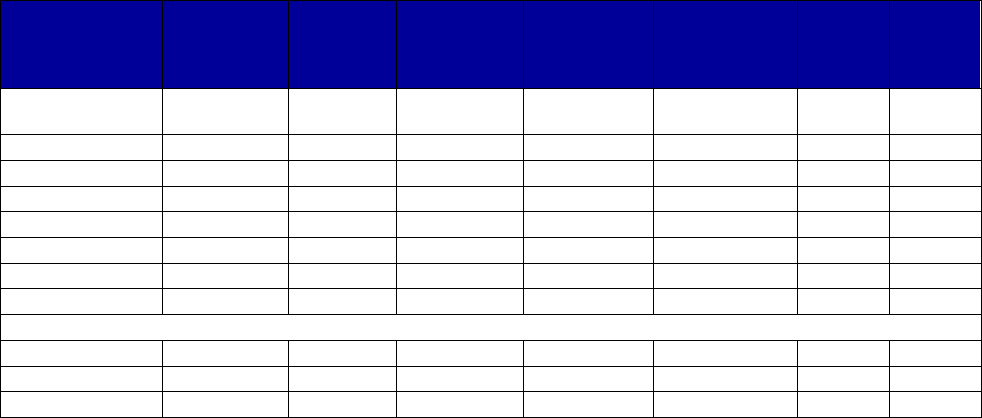

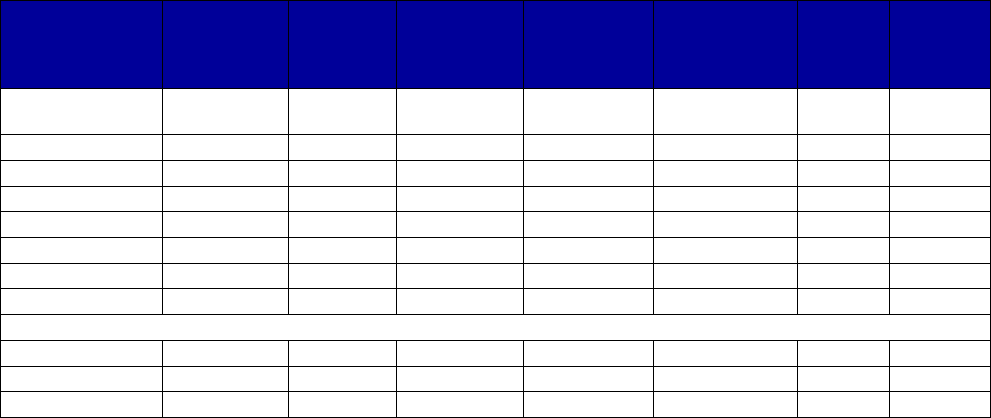

Coverage Versus Preferred Status

of MAT and Overdose Reversal Drugs

(number of states and territories)

Drug Coverage Preferred Status

• Acamprosate 40 27

• Buprenorphine 52 29

• Buprenorphine implant 37 2

• Buprenorphine injection

extended-release (ER) 33 7

• Buprenorphine-naloxone 52 51

• Disulfiram 49 32

• Methadone 42 —

• Naloxone 51 43

• Naltrexone (oral) 51 44

• Naltrexone ER 51 34

• Includes the 50 states, District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the US

Virgin Islands

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

4

other MAT drugs. However, one state requires prior authorization for all drugs in the opioid

dependence treatment class.

As part of the authorization process, several states require evidence that the patient was

being referred or was concurrently receiving psychosocial treatment with their

medications. This requirement is most often applied to medications for opioid use disorders,

particularly buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone.

Step therapy is another drug utilization management strategy that requires patients to try

a first-line medication, such as a generic medication, before they can receive a second-line

treatment, such as a brand name medication. This requirement is relatively common.

However, some states also impose step therapy requirements across medications types, in which

a drug may not be used unless one or more other specific drugs are tried unsuccessfully first.

One example might include requirements to try naltrexone before disulfiram or acamprosate.

Quantity or dosing limits often are used by Medicaid programs to avoid potential abuse or

misuse of a medication, promoting safe and appropriate medication use. Such limits are

used by 45 and 46 states for buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone, respectively. In

addition to quantity limits, some states historically have established lifetime treatment limits,

most commonly applied to buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone. However, lifetime limits

are disappearing, which is consistent with clinical evidence and best practices, given that

addiction is a chronic disease.

Key Findings on Innovative Approaches to Financing and Delivering MAT

States are using a variety of innovative approaches to finance and deliver medications for

alcohol and opioid use disorders. For example, Massachusetts is addressing the opioid

addiction epidemic by expanding medication access through a nurse care manager model. This

model allows physicians to treat more patients with buprenorphine and has proven to be cost-

effective. Another example is Missouri, which has begun the process of integrating MAT into

all SUD treatment in the state. Missouri currently is requiring any SUD treatment provider that

contracts with the state to offer MAT either directly or by referral. To ensure that providers are

fairly compensated for the provision of MAT, the state has taken steps to establish an equitable

reimbursement model that covers medications, the act of administration, laboratory services,

other MAT-related activities, and overhead costs. The state of Washington has implemented a

pilot involving a telemedicine project, Flex Care, at the Grays Harbor Clinic in the township of

Hoquiam (about 2 hours southeast of Seattle). Approximately 200 patients in rural coastal

Washington who previously had no access to MAT for their opioid dependence disorder now

receive MAT under the Flex Care treatment model.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

5

I. Introduction

Addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug or

alcohol seeking and use, despite harmful consequences (National Institute on Drug Abuse

[NIDA], 2016a). Drug-induced deaths have become a leading public health concern in the

United States, with opioid overdose and mortality rising at an especially alarming rate. It is

estimated that more than 72,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2017 and more than

63,000 in 2016 (NIDA, 2018). In 2016, more than 6 out of 10 of these deaths involved an opioid

(Seth et al., CDC MMWR, 2018). Opioid overdose

deaths (including both opioid pain relievers and

heroin) reached record levels in 2016, with an age-

adjusted 27.9 percent increase in just 1 year (Seth et

al., CDC MMWR, 2018). The use of illicit drugs,

including opioids, also is linked to a variety of

adverse health events (Devlin & Henry, 2008;

NIDA, 2012a).

Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality also present serious public health concerns. Each year

in the United States, an estimated 88,000 deaths are attributed to the use of alcohol (Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with

adverse health and social consequences, including liver cirrhosis, certain cancers, fetal alcohol

spectrum disorder, unintentional injuries, and violent behaviors (Bouchery, Harwood, Sacks,

Simon, & Brewer, 2011). Substance use disorder (SUD) also is associated with high costs to

both individuals and society (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

[SAMHSA], 2014a).

Addiction, like many other chronic diseases, is a treatable condition. According to NIDA,

“treatment enables individuals to counteract addiction’s powerful effects on the brain and

behavior and allows them to regain control of their lives. According to research that tracks

individuals in treatment over extended periods, most people who get into and remain in treatment

stop using drugs, decrease their criminal activity, and improve their occupational, social, and

psychological functioning” (NIDA, 2012b). There are a variety of evidence-based approaches to

treating addiction. For alcohol and opioid use disorders, treatment can include psychosocial

treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or contingency management), medications, or a

combination of approaches. Although reliance on medication alone is not uncommon, a

combination of psychosocial treatment and medication generally is recommended for the

treatment of alcohol or opioid use disorders. Treatment that incorporates medication is referred

to as medication-assisted treatment or MAT. MAT for opioid use disorders using buprenorphine

or methadone is associated with substantial reductions in the risk for all cause and overdose

mortality (Sordo et al., 2017).

Substance Use-Related Deaths

There were over 63,000 drug

overdose deaths in 2016. Six out of

10 involved an opioid.

An estimated 88,000 deaths are

attributed to alcohol use annually.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

6

Medications can help individuals with SUDs re-establish normal brain functioning, prevent

relapse, and reduce cravings (NIDA, 2016b). The following medications have been approved by

the FDA for treatment of alcohol and opioid use disorders:

2

Alcohol use disorders—

• Acamprosate

• Disulfiram

• Naltrexone (oral)

• Naltrexone extended release

(injectable)

Opioid use disorders—

• Buprenorphine

• Buprenorphine extended release

(subdermal and injectable)

• Buprenorphine-naloxone

• Methadone

• Naltrexone (oral)

• Naltrexone extended release

(injectable)

In 2016, an estimated 21.0 million people aged 12 years or older in the United States needed

treatment for an illicit drug or alcohol use disorder (SAMHSA, 2017). SAMHSA found that only

10.6 percent of individuals (2.2 million people) who needed substance use treatment for illicit

drug or alcohol use had received it at a specialty facility in the past year. Among individuals

who recognized a need for treatment and tried to obtain it, lack of health coverage was the most

frequently reported reason (reported by 37.9 percent of those individuals) for not receiving

treatment (SAMHSA, 2017). Health insurance significantly increases access to SUD treatment

by making it more affordable. Medicaid is a critical payment source and is one of the largest

single payers of medications for treating SUDs. Medicaid was responsible for 25 percent of

SUD-related spending in 2014, and that share is projected to increase to 28 percent by 2020

(SAMHSA, 2014b). The primary purpose of this report is to present information about Medicaid

coverage of medications used to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders.

3

This report serves as an

update to the SAMHSA report Medicaid Coverage and Financing of Medications to Treat

Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders (SAMHSA, 2014c).

In addition to describing the treatment and cost-effectiveness of these medications, the first

section of this report reviews policies and regulations that affect coverage of and access to them.

The second section describes Medicaid coverage of these medications for all 50 states, the

District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in the second and third quarters of

2018, and it explains the different benefit design elements most commonly used for each

medication. The third section provides examples of the way that states are using innovative

financing and delivery models to achieve positive outcomes and addresses some cross-cutting

best practices that may help increase access to SUD medications.

2

In addition, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of naloxone for the reversal of opioid

overdose.

3

Medications intended for the treatment of nicotine or tobacco use are excluded.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

7

II. State Considerations for Covering Medications

for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders

State Medicaid agencies typically use a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee or equivalent

body to (1) determine whether to provide reimbursement for new medications, (2) determine

whether to provide preferred or nonpreferred status for those medications, and (3) reconsider the

status of coverage of existing medications. Sometimes a separate drug utilization review

committee may contribute to the process. Usually, a new medication requires prior authorization

until a preferred or nonpreferred status is designated for the drug. Although priority reviews can

be enacted when appropriate, preferred or nonpreferred status and other coverage decisions can

generally take up to 6 months. The committee approval process often includes literature and

evidence review, efficacy determination, proposed protocol provisions, and safety and cost

considerations (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2013).

This section presents topics that members of Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committees may consider

as they determine whether medications for alcohol or opioid use disorders will be available as

indicated on the Medicaid formulary or Preferred Drug List (PDL). These topics include evidence

regarding the treatment efficacy of these medications, their cost-effectiveness and cost offset, and

policies and regulations that may affect their coverage in Medicaid.

A. Efficacy of Medications Used to Treat Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders

Before determining whether to provide coverage for a drug or whether to include it on a PDL, state

Medicaid agencies examine evidence of efficacy. These drugs are ones that the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) already has approved for prescribing. It is important to note, however, that,

although the FDA approves drugs for certain indications, it does not decide how doctors use these

drugs or whether and to what extent Medicare,

Medicaid, and private insurers will cover drug costs.

Those are independent decisions made once the FDA

has approved the drug for release on the market.

The FDA evaluates a product’s safety and efficacy but

does not formally consider cost as part of the drug

approval process. The FDA approves drugs for

certain conditions or indications that then are reflected

on product labels. However, once these medications

are approved by the FDA, health care professionals

also may prescribe them “off-label” for other uses.

After receiving initial approval for treating one or

more given conditions, the manufacturer also may

subsequently seek FDA approval for use of the

Brand Versus Generic

Brand-name drugs are patented and

marketed by the manufacturer after

undergoing extensive research and

subsequent FDA approval. Once the

patent expires, other manufacturers

can produce generic equivalents, or

generics, that are required by the

FDA to be therapeutically equivalent

to the branded version. Generic

equivalents are typically priced much

lower than existing brand

medications.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

8

product for other indications or for a new route of administration or form (e.g., tablet or liquid) of

the medication (FDA, 2017a, 2017b). All the medications reviewed in this section are ones that

have met the FDA requirements for substantial evidence of safety and efficacy and were approved

by the FDA for the treatment of alcohol or opioid use disorders. After a brand-name drug’s

patents and other exclusivity have expired, a generic drug product may become available. The

FDA describes generic drugs as “copies of brand-name drugs and are the same as those brand

name drugs in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance

characteristics and intended use” (FDA, 2017c). Although not always the case, generic drug

product prices may be up to 85 percent lower than their brand-name counterparts (FDA, 2017d).

For this reason, many PDLs will list generic drugs if one has been approved by FDA.

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorders

The medications currently approved by the FDA for treatment of alcohol use disorders are

acamprosate (also available as Campral®), disulfiram (also available as Antabuse®), oral naltrexone,

and extended-release injectable naltrexone (only available as Vivitrol®) (Table 1). Extended-release

injectable naltrexone and acamprosate were developed more recently than the other medications;

extended-release injectable naltrexone is not yet available in generic form. In general, scientific

research has found that these medications for alcohol use disorders help maintain abstinence, reduce

the risk of relapse, and reduce heavy drinking (Laaksonen, Koski-Jannes, Salaspuro, Ahtinen, &

Alho, 2008; Maisel, Blodgett, Wilbourne, Humphreys, & Finney, 2013; Mason & Lehert, 2012;

Specka, Heilmann, Lieb, & Scherbaum, 2014). Each is discussed briefly below.

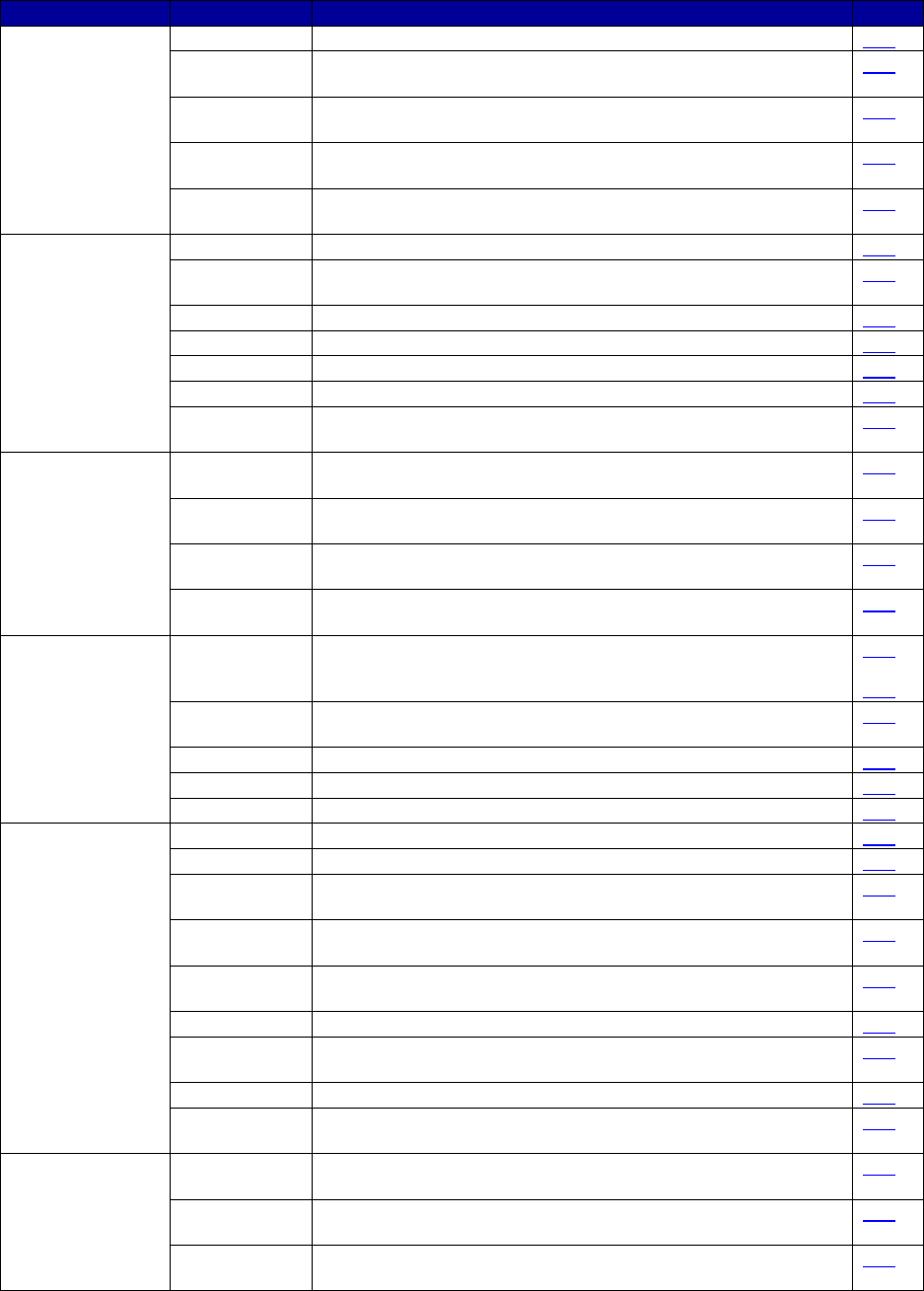

Table 1. Medications Used to Treat Alcohol Use Disorders

Medication

Year of First

FDA

Approval

a

Mechanism of Action

Is a Generic

Version

Available?

Acamprosate

calcium (oral)

(Campral)

2004

Possible glutamate antagonist and gamma-

aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist (not fully

known)—reduces symptoms of withdrawal

and craving

Yes

Disulfiram (oral)

(Antabuse)

1951

Alcohol antagonist—disulfiram plus alcohol

will produce flushing, throbbing in head and

neck, headache, nausea, vomiting, and other

highly unpleasant symptoms

Yes

Naltrexone (oral)

1994 (for

alcohol use

disorders)

Opioid antagonist—blocks opioid receptors

that are involved in alcohol and opioid

cravings

Yes

Naltrexone

(extended-release

injectable) (Vivitrol)

2006

Opioid antagonist—blocks opioid receptors

that are involved in alcohol and opioid

cravings

No

Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

a

For more information on FDA approval of drugs, see U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA:

FDA Approved Drug Products. Retrieved from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

9

Acamprosate. Acamprosate is an oral medication that is used for postwithdrawal maintenance

of alcohol abstinence. Short-term and long-term studies provide evidence of the efficacy of

acamprosate. For example, acamprosate is effective at increasing the cumulative days of

abstinence among individuals with alcohol use disorders (Bouza, Angeles, Ana, & María, 2004;

Donoghue et al., 2015; Maisel et al., 2013; Mann, Lehert, & Morgan, 2004; Rösner et al, 2011;

SAMHSA, 2009). This medication is associated with significantly higher rates of treatment

completion and medication compliance and has a significant effect compared with placebo in

improving rates of abstinence and no heavy drinking in people with alcohol use disorders

(Mason & Lehert, 2012). Acamprosate may be most effective among individuals who are

motivated for complete abstinence from alcohol and when provided over a long period of time.

Disulfiram. Disulfiram is the oldest medication used in the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

The medication, administered orally as a tablet, does not prevent alcohol craving; instead, it

deters subsequent alcohol consumption by causing unpleasant effects such as flushing, throbbing

headache, nausea, vomiting, and other unpleasant symptoms for 24–30 hours after taking the

medication. Research shows that, when taken consistently and under supervision, disulfiram

increases abstinence, prevents relapse, and decreases the frequency of alcohol consumption

(Brewer, Meyers, & Johnsen, 2000; SAMHSA, 2009; Specka, Heilmann, Lieb, & Scherbaum,

2014). The mechanism of action for disulfiram, an aversive reaction upon drinking alcohol,

may, however, lead to poor adherence. Consequently, expert consensus recommends using

disulfiram only with reliable and highly motivated individuals in monitored situations (in which

another person administers the medication) or in circumstances in which it is necessary to deter

an anticipated high-risk situation (Garbutt, 2009; Jorgensen, Pedersen, & Tonnesen, 2011; Mann,

2004; Suh, Pettinati, Kampman, & O’Brien, 2006).

Naltrexone (oral and injectable). Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that is used to prevent the

reinforcing effects of alcohol and opioids. It has the advantages of not being addictive and not

reacting aversively with alcohol (Leavitt, 2002; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and

Alcoholism, 2008). The FDA initially approved oral naltrexone for treating alcohol use

disorders in 1994.

In 2006, the FDA approved the injectable, extended-release formulation of naltrexone (known by

its trade name, Vivitrol) for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. This formulation is more

expensive than the oral form and is given once every 4 weeks rather than taken daily. Monthly

intramuscular injection has a clear advantage over the daily oral formulation because it is

clinically well-tolerated (occasional side effects in some patients may include pain and

tenderness at the injection site) and is more effective for patients who do not adhere well to a

daily oral regimen of naltrexone. Consistent bioavailability of the long-acting formulation

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

10

contributes to an improved adverse effect profile compared with its oral counterpart (Clapp,

2012; Mannelli, Peindl, Masand, & Patkar, 2007).

4

Many literature reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have found that the

use of naltrexone for alcohol use disorders is effective at reducing the number of heavy drinking

days, alcohol-related mortality, and alcohol craving (Bouza et al., 2004; Garbutt et al., 2005;

Harris et al., 2015; Helstrom et al., 2016; Jonas et al., 2014; Lobmaier, Kunøe, Gossop, & Waal,

2011; Maisel et al., 2013; Pettinati et al., 2006; SAMHSA, 2009). Studies also have shown less

frequent relapses. It is commonly reported that naltrexone is most effective at significantly

improving drinking outcomes when the drug therapy is used in conjunction with psychosocial

support. In addition, its benefits are more pronounced for patients who stopped drinking alcohol

prior to entering treatment (lead-in abstinence). Genetic factors and adherence play a significant

role in the effectiveness of naltrexone (Chamorro et al., 2012; Volpicelli et al., 1997).

Medications for Opioid Use Disorders

Scientific research has established that treatment of opioid addiction with medication (1)

increases patient retention in treatment; (2) improves social functioning; and (3) decreases drug

use, infectious disease transmission, criminal activities, and the risk of overdose and death

(Connock et al., 2007; Gowing, Farrell, Bornemann, Sullivan, & Ali, 2011; Johnson et al., 2000;

Kinlock et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2013; Soyka, Zingg, Koller, & Kuefner, 2008; Thomas et

al., 2014; Woody et al., 2015; Zaric, Brandeau, & Barnett, 2000).

Medications currently approved for the management of opioid use disorders include

buprenorphine (available as Probuphine® [extended-release subdermal {implant}]), Sublocade®

[extended-release injectable], and in a sublingual formulation); buprenorphine-naloxone

(sublingual) (also available as Bunavail® [buccal], Suboxone® [sublingual], or Zubsolv®

[sublingual]); methadone (generally dispensed orally for MAT) (also available as Dolophine®)

oral naltrexone; and extended-release injectable naltrexone (only available as Vivitrol) (Table 2).

Generic versions of buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone were made available in 2009

and 2013, respectively. Extended-release injectable naltrexone and the extended-release

subdermal and injectable forms of buprenorphine are the only medications for the treatment of

opioid use disorders that are not available in at least one generic form. Each of these

medications is discussed briefly below.

4

More information about extended-release injectable naltrexone is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=021897

).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

11

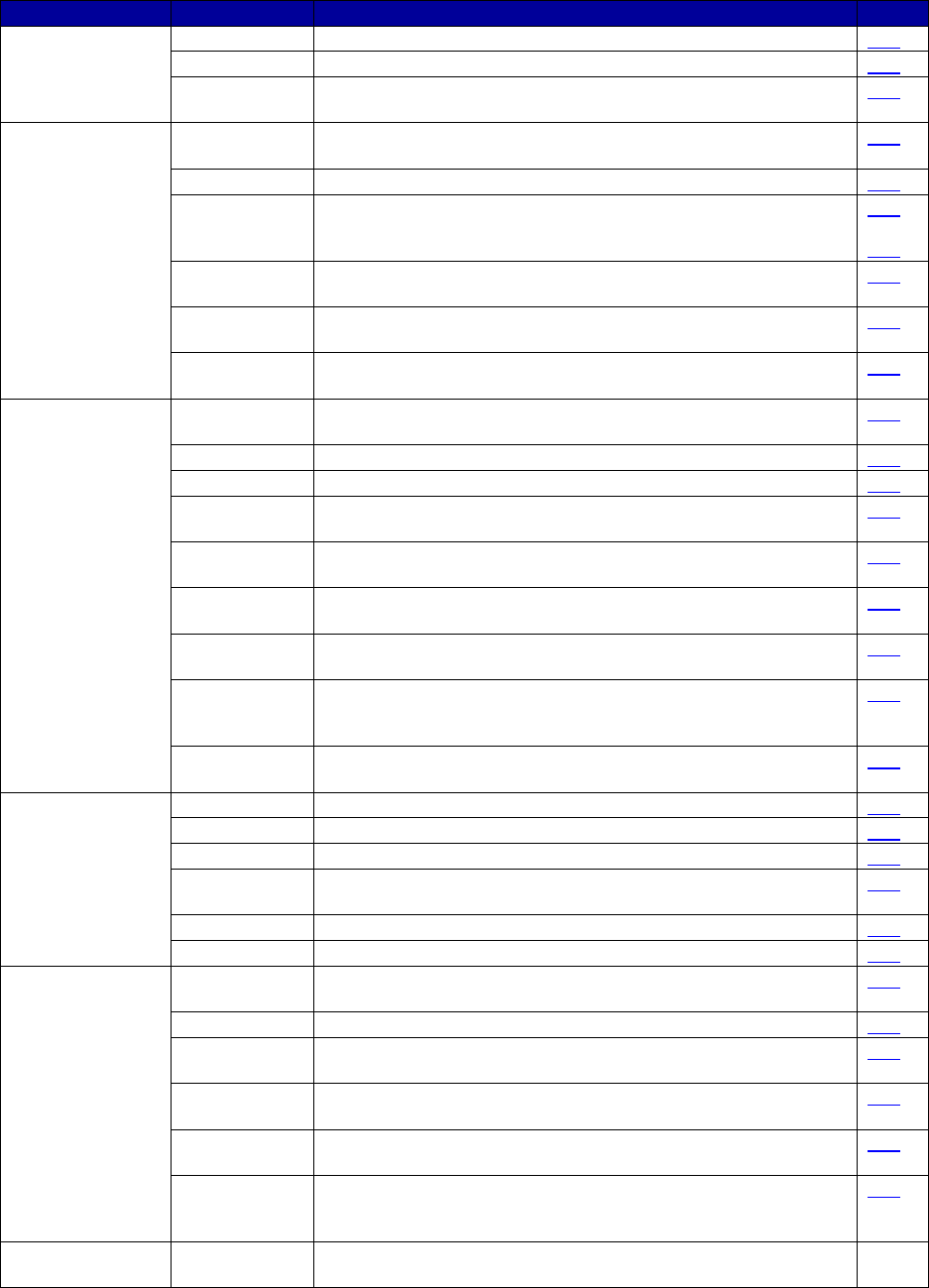

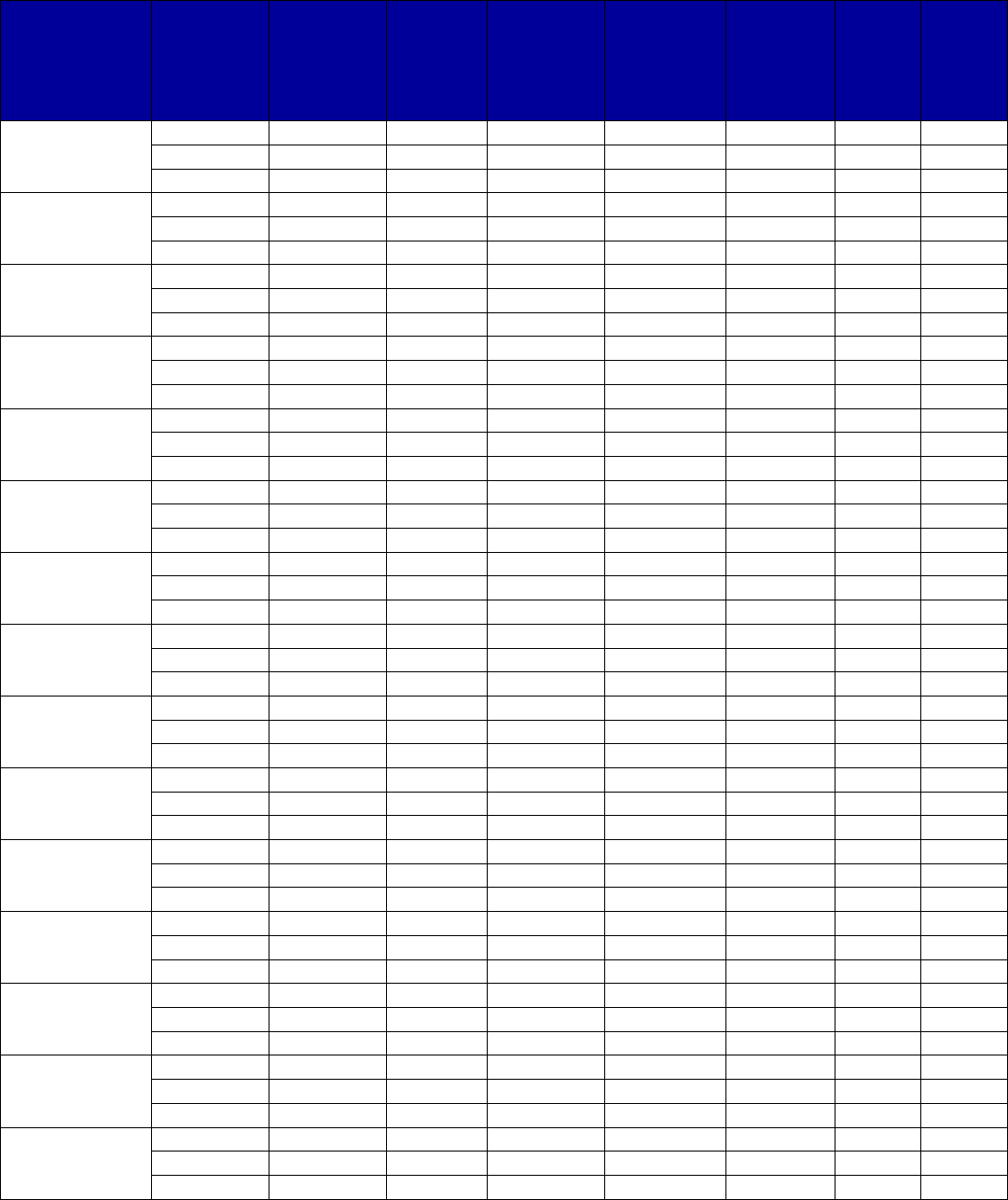

Table 2. Medications Used to Treat Opioid Use Disorders

Abbreviation: FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Medication

Year of

First FDA

Approval

a

Mechanism of Action

Is a

Generic

Version

Available?

Buprenorphine

(sublingual)

2002

Partial-opioid agonist—attaches to opioid receptors

but produces only a limited opioid-like effect while

competitively inhibiting other opioids from attaching

to and fully activating the receptor. These

properties allow it to relieve withdrawal and reduce

cravings while blocking other opioids.

Yes

Buprenorphine

(subdermal/implant)

(Probuphine)

2016

Partial-opioid agonist—attaches to opioid receptors

but produces only a limited opioid-like effect while

competitively inhibiting other opioids from attaching

to and fully activating the receptor. These

properties allow it to relieve withdrawal and reduce

cravings while blocking other opioids for up to 6

months.

No

Buprenorphine

(extended-release

injectable)

(Sublocade)

2017

Partial-opioid agonist—attaches to opioid receptors

but produces only a limited opioid-like effect while

competitively inhibiting other opioids from attaching

to and fully activating the receptor. These

properties allow it to relieve withdrawal and reduce

cravings while blocking other opioids for up to a

month.

No

Buprenorphine/

naloxone (oral,

Bunavail [buccal],

Suboxone

[sublingual], Zubsolv

[sublingual])

2002

Opioid antagonist (naloxone) added to

buprenorphine to deter misuse by injection. If

buprenorphine/naloxone is injected, the user can

experience acute withdrawal.

Yes

Methadone (oral)

(Dolophine)

1947

Full-opioid agonist—attaches to opioid receptors

and produces a full range of opioid effects. Full

agonists differ from partial agonists in that, the

higher the dose, the greater the effect they produce.

Methadone is extremely long acting. When taken

daily at an effective dose, it relieves withdrawal and

reduces cravings. It also saturates the available

opioid receptors and inhibits the effects of other

opioids that may be ingested.

Yes

Naltrexone (oral)

1984 (for

opioid use

disorders)

Opioid antagonist— attaches to opioid receptors but

produces no opioid-like effect and prevents opioids

acting at the receptor.

Yes

Naltrexone

(extended-release

injectable) (Vivitrol)

2010

Opioid antagonist— attaches to opioid receptors but

produces no opioid-like effect and prevents opioids

acting at the receptor for up to a month.

No

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

12

a

For more information on FDA approval of drugs, see U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA:

FDA Approved Drug Products. Retrieved from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

Buprenorphine, buprenorphine extended-release, and buprenorphine-naloxone. Buprenorphine

5

is a partial opioid agonist. Buprenorphine alone, when administered sublingually, is indicated

for the induction phase of opioid use disorder treatment (National Library of Medicine, 2017) or

for maintenance therapy during pregnancy (SAMHSA, 2016a). A recently approved implantable

form of buprenorphine (Probuphine) is available for maintenance pharmacotherapy for opioid

use disorder for patients who have been stabilized at a low or moderate dose (FDA, 2016a).

6

An

extended-release injectable formulation (Sublocade) is available for treatment of moderate to

severe opioid use disorder in patients who have initiated treatment with a transmucosal

buprenorphine-containing product, and who have been on a stable dose for at least 7 days (FDA,

2017e).

7

Buprenorphine combined with naloxone

8

can be used for withdrawal and induction as well as for

the maintenance phase of treatment. FDA approved the oral generic form in 2013 (Formulary

Watch, 2013), but the medication also is marketed under the brand names of Bunavail (buccal),

Suboxone (sublingual), and Zubsolv (sublingual). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist widely used

as the antidote to opioid poisoning. It is combined with buprenorphine to reduce the risk of

buprenorphine being misused by injection. Naloxone is addressed in greater detail separately

regarding its use in managing opioid overdose.

Several comprehensive reviews have concluded that there is a high level of evidence from many

randomized clinical trials indicating that buprenorphine is a safe and effective treatment for

opioid use disorders (Amass et al, 2012; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2014; Thomas et al.,

2014). The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guidelines for

the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use (ASAM, 2015)

provides concrete guidance on the use of buprenorphine for induction and maintenance as well as

for use with special populations such as pregnant women.

Two recent studies provide information on the potential effects of insurer dose limits for

buprenorphine-naloxone use. The first study investigated the effect of dose limits paired with

prior authorization within the Massachusetts Medicaid program, in which the requirements for

prior authorization increased in frequency as dose limits increased (Clark et al., 2014). The

5

More information about buprenorphine is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=078633

).

6

More information about implantable buprenorphine is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/204442s006lbl.pdf

).

7

More information about extended-release injectable buprenorphine is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/209819s001lbl.pdf

).

8

More information about buprenorphine-naloxone is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=091149

).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

13

results showed that the change effectively reduced the number of enrollees receiving high doses

but did not affect total health care cost for those patients. There was, however, a short-term

increase in relapses among individuals who were switched to lower doses, suggesting that the

change was initially difficult for certain patients. The second study conducted elsewhere found

that those with higher buprenorphine-naloxone doses had fewer aberrant drug tests and greater

retention in treatment than those required by a payer to reduce their dosage to 16 mg/day or

lower (Accurso & Rastegar, 2016).

Methadone. Maintenance treatment with methadone

9

has been used for many decades in the

United States. Pharmacologically, methadone is a full-opioid agonist in that it attaches to opioid

receptors and produces a full range of opioid effects, with greater effects at higher doses.

Methadone is extremely long acting (24–30 hours). When

taken daily at an effective dose, it relieves withdrawal and

reduces cravings. It also saturates the available opioid

receptors and inhibits the effects of other opioids that may

be ingested. Because the medication is taken orally and

has a slow and very long period of metabolism, it does not

generate the extreme euphoria of short-acting, injectable

opioids (e.g., heroin or many pharmaceutical opioids) in

properly prescribed doses (Rettig & Yarmolinsky, 1995).

Because methadone is an opioid and produces opioid

effects, however, its use for treatment is sometimes

controversial.

A high level of evidence from multiple randomized

controlled trials over the past 4 decades supports

methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) as an effective

method to reduce craving, use of opioids, and mortality.

Additionally, MMT usually improves health and social

functioning (Faggiano, Vigna-Taglianti, Versino, &

Lemma, 2003; Fullerton et al., 2014; Mattick, Breen,

Kimber, & Davoli, 2014; SAMHSA, 2012; Sordo et al.,

2017; Soyka et al., 2008).

Naltrexone (oral and injectable). The FDA first approved

naltrexone in 1984 as an oral agent for treating opioid use

disorders. Naltrexone is a long-acting opioid antagonist

that works by tightly binding to opioid receptors for 24–30

9

More information about methadone is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/017116s021lbl.pdf

).

Diversion Potential of

Buprenorphine

Policymakers have expressed

concern about the potential for

abuse of buprenorphine. In

making decisions about

coverage, it is important to weigh

the potential harm from diversion

against the consequences of

limiting access to effective

treatment. Poison control centers

and emergency departments

have reported that, among adults,

fewer emergency visits related to

buprenorphine reflect life-

threatening situations and result

in hospital admission than visits

related to the use of heroin,

methadone, or oxycodone

(Bronstein et al., 2009).

Buprenorphine-naloxone also has

been reformulated to an

individually packaged sublingual

film version in efforts to reduce its

potential for diversion as well as

its accidental use by children

(Clark & Baxter, 2013).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

14

hours (oral) or up to 30 days (extended-release injection). This makes the opioid receptors

unavailable for activation should the individual subsequently take any opioid. Studies have

found that naltrexone

10

can be effective at decreasing relapse to illicit opioid use (SAMHSA,

2012); however, this result is dependent on adherence to treatment, which often is low for oral

naltrexone (Johansson, Berglund, & Lindgren, 2006; Swift, Oslin, Alexander, & Forman, 2011)

because those being treated must be abstinent to use the medication (O’Connor & Fiellin, 2000).

In 2010, FDA approved the extended-release injectable formulation of naltrexone

11

(Vivitrol) for

treating opioid use disorders. Studies have found that it produces significantly better retention in

treatment and lower rates of opioid relapse (Brooks et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2016) as well as

significantly lower opioid-related mortality compared with no treatment (Harris et al., 2015).

However, to prevent severe iatrogenic opioid withdrawal, patients must abstain from opioids for

a minimum of 7 days before beginning the naltrexone treatment; thus, it is effective when used

following medical detoxification from opioids or after a period of abstinence such as during

incarceration. Some literature suggests that counseling or other supports may be beneficial to

encourage continuation in treatment among some individuals receiving extended-release

injectable naltrexone (Brooks et al., 2010). Barriers to the use of extended-release injectable

naltrexone may include complexity of ordering and using the medication, cost, health plan

reimbursement policies, and lack of knowledge about the drug (Alanis-Hirsch et al., 2016).

Recent studies have shown that, although extended-release injectable naltrexone is effective for

preventing relapse to opioid use, its use is not as widespread compared with other

pharmacotherapies, in part because of cost and its more limited inclusion in payer formularies

(Lee, Kresina, Campopiano, Lubran, & Clark, 2015).

A recent randomized, multistate controlled clinical trial with criminal justice offenders

demonstrated effective results using extended-release injectable naltrexone to prevent opioid

relapse, with the use of this drug resulting in a longer median time to relapse compared with

usual treatment (Lee et al., 2016; NYU Langone Medical Center, 2016). It is important to

provide viable assistance to this population, which has a high potential for relapse, high risk of

mortality from drug overdose, and risk of repeated interactions with the criminal justice system.

These patients also are less likely to have access to other medications such as buprenorphine or

methadone, so extended-release injectable naltrexone may be the most effective treatment for

them.

Medications for Opioid Overdose

Naloxone. Naloxone is a short-acting opioid antagonist that has been demonstrated to be safe

and effective at reversing opioid-induced respiratory depression from opioid overdose (FDA,

10

More information about oral naltrexone is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/018932s017lbl.pdf

).

11

More information about extended-release injectable naltrexone is available on the FDA drug label

(https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=BasicSearch.process

).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

15

2015; Hawk, Vaca, & D’Onofrio, 2015; van Dorp, Yassen, & Dahan, 2007). Naloxone currently

requires a prescription but has no abuse potential; it is not a controlled substance.

Over the past 40 years, naloxone has been used with good outcomes in the emergency

department and in hospital settings for opioid overdose reversal; it has an excellent safety profile,

and reported side effects have been rare (Burris, Norland, & Edlin, 2001; Davis, Ruiz, Glynn,

Picariello, & Walley, 2014). It initially was administered intravenously and later became

available intramuscularly (Evzio

®

). In 2015, the FDA approved the marketing of intranasally

administered naloxone (Narcan

®

). Increasingly, naloxone is being administered by

nonprofessionals in its intramuscular and intranasal forms (FDA, 2015), allowing administration

outside the hospital and emergency department by bystanders and professional first responders

(Mueller, Walley, Calcaterra, Glanz, & Binswanger, 2015; Wickramatilake et al., 2017). The

reader is referred to the SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit for more information

about naloxone (SAMHSA, 2016b).

Cost Offset and Cost Effectiveness of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid

Use Disorders

State Medicaid programs also examine the cost offset

and cost-effectiveness of medications used for alcohol

and opioid use disorders to determine whether to

reimburse for them and whether to place them on a

PDL. In doing so, states will take account of the high

costs associated with alcohol and opioid misuse and

use disorders.

Alcohol Use Disorder Costs

In 2010, excessive drinking costs the United States

were estimated at almost $250 billion annually

(Sacks, Gonzales, Bouchery, Tomedi, & Brewer,

2010). Studies of the comparative effectiveness of different treatments for alcohol use disorders

have found greater savings from use of MAT than from use of psychosocial treatment alone.

The following are findings from studies examining alcohol treatment, which relied on

retrospective claims data and did not distinguish those who received MAT alone from those who

received it in conjunction with counseling:

Total health care costs were 30 percent less for those who received MAT than for those

who did not (Baser, Chalk, Fiellin, & Gastfriend, 2011). This study compared costs for

those who received MAT with those who received only psychosocial therapy. Health

care costs were 34 percent greater for those receiving acamprosate than for those

receiving disulfiram, oral naltrexone, or extended-release injectable naltrexone.

Cost offset is defined as the

economic savings from an

intervention after accounting for the

economic costs of that intervention.

Cost-effectiveness is defined as

the comparison between the

relative costs and outcomes of an

intervention that is typically

quantified in an individual’s quality-

adjusted life years.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

16

Individuals treated with MAT compared with those who did not receive MAT incurred

less expense related to alcoholism-related inpatient hospitalizations and detoxification,

with extended-release injectable naltrexone reducing those costs the most (Mark,

Montejano, Kranzler, Chalk, & Gastfriend, 2010).

Use of extended-release injectable naltrexone resulted in the largest reduction in

nonpharmacy health care spending, compared with disulfiram, oral naltrexone,

acamprosate, or psychosocial therapy only (Bryson, McConnell, Korthuis, & McCarty,

2011).

Treatment with implanted naltrexone was associated with reduced health care events and

reduced costs of hospital admission and emergency department visits in patients treated

for alcohol use disorders in the first 6 months following treatment compared with those

who did not receive implanted naltrexone (Kelty et al., 2014).

A meta-analysis of studies indicated that health care utilization and costs were generally

equivalent to or lower for patients receiving extended-release injectable naltrexone

relative to patients receiving other alcohol use disorder agents (Hartung et al., 2014).

Opioid Use Disorder Costs

The economic consequences of opioid use disorders also are substantial. Annual health care

expenditures for individuals with an opioid use disorder are estimated to be almost nine times

higher than annual expenditures for those without such a disorder (White et al., 2005). The total

economic burden associated with fatal overdose, misuse, and use disorder attributable to

prescription opioid misuse in 2013 was estimated to be $78.5 billion, of which $28.9 billion was

associated with increased health care and SUD treatment costs and one-quarter was associated

with public sector health care, treatment, and criminal justice costs (Florence, Zhou, Luo, & Xu,

2016). A recent analysis in Australia also revealed substantial crime-related costs in that country

associated with heroin disorders (Dunlop et al., 2017).

As discussed below, cost-effectiveness and comparative effectiveness studies regarding opioid

treatment found greater savings from use of MAT than from use of psychosocial treatment alone.

Most of these studies, however, do not address whether those in the groups receiving MAT also

received counseling, although a study of the cost-effectiveness of adherence to buprenorphine

treatment did consider, among other things, the impact on outpatient treatment costs. These

studies relied primarily on claims data and one used predictive modeling but excluded the cost of

counseling. These studies are summarized below:

The odds and costs of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and detoxification

admissions were greatest for those without treatment, followed by those treated without

medication, followed by those treated with buprenorphine, and finally followed by those

treated with methadone. In contrast, annual cost per patient was lower for those taking

buprenorphine than for those taking methadone largely because of longer hospitalizations

for those receiving methadone (Clark, Samnaliev, Baxter, & Leung, 2011).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

17

Patients who did not receive pharmacotherapy had higher costs for detoxification,

rehabilitation, and both opioid-related and non-opioid-related hospitalizations. Among

those treated with medication, the highest drug costs were for extended-release injectable

naltrexone, whereas the highest overall costs were for methadone, apparently because of

a far higher number of non-opioid-related hospitalizations (Baser et al., 2011).

A meta-analysis of opioid dependent

extended-release injectable naltrexone

patients found they had lower inpatient

substance abuse-related utilization than

patients treated with other agents and

lower total cost than patients treated

with methadone (Hartung et al., 2014).

A study of the cost-effectiveness of

buprenorphine, which compared

individuals who were treatment

adherent with those who were not,

found that, although use of

buprenorphine resulted in increased

pharmacy costs ($6,156 vs. $3,581),

other costs—including outpatient

($9,288 vs. $14,570), inpatient

($10,982 vs. $26,470), emergency

department ($1,891 vs. $4,439), and

total health care costs ($28,458 vs.

$49,051)—were less (Tkacz,

Volpicelli, Un, & Ruetsch, 2014).

A study that modeled the incremental

cost-effectiveness of extended-release

injectable naltrexone, methadone, and

buprenorphine for adult males with

opioid dependence from the perspective

of state addiction treatment payers

found that the expected per patient cost

of a 24-week treatment period was

$1,390.98 for methadone, $1,837.40 for

buprenorphine, and $4,287.73 for

extended-release injectable naltrexone

(Jackson, Mandell, Johnson, Chatterjee,

& Vanness, 2015).

Controlled Substance Schedules

Substances deemed to be “controlled” under

the Controlled Substances Act are divided

into five schedules. Substances are placed in

their respective schedule on the basis of

whether they have a currently accepted

medical use in the United States, their relative

abuse potential, and their likelihood of

causing dependence when abused.

Controlled substances are overseen by the

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Drugs are scheduled by DEA in coordination

with the FDA.

Schedule I substances have no currently

accepted medical use in the United States, a

lack of accepted safety for use under medical

supervision, and a high potential for abuse.

Schedule II substances, which include

methadone and most opioid pain relievers,

have high potential for abuse and may lead to

severe psychological or physical dependence.

Schedule III substances, which include

buprenorphine, have less abuse potential

than those in Schedules I or II. Abuse may

lead to moderate or low physical dependence

or high psychological dependence.

Schedule IV substances have lower abuse

potential relative to those listed in Schedule III.

Schedule V substances have low abuse

potential relative to those listed in Schedule

IV, and they have preparations containing

limited quantities of certain narcotics.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

18

State and Federal Regulations and Policies Affecting the Prescription and

Dispensing of Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders

In addition to considerations related to efficacy and cost-effectiveness, federal and state laws and

other policies may affect the prescribing and dispensing of medications for alcohol and opioid

use disorders. In this section, we address some of the most important statutes, regulations, and

other policies.

Federal Laws Governing Methadone and Buprenorphine

Medications for treatment of alcohol and opioid use disorders must be prescribed or dispensed by

individuals who are licensed to perform these activities in their respective states; however,

additional rules and regulations apply to methadone and buprenorphine because of their status as

controlled substances under the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act

(Controlled Substances Act, 1970). The rules and regulations affect access to these medications

regardless of insurance coverage.

Methadone is a Schedule II drug that is used for the treatment of both pain and opioid addiction

(U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). When prescribed for pain, it may be dispensed by a

pharmacy. For treating opioid addiction, however, methadone may be dispensed only through an

opioid treatment program (OTP) that has been certified by SAMHSA and registered as a narcotic

treatment program by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) (SAMHSA, 2015).

Buprenorphine is a Schedule III drug (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.), indicating its lower

potential for abuse or misuse than Schedule II substances. Pursuant to the Drug Addiction

Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000), qualified physicians can prescribe buprenorphine to

patients for the treatment of opioid use disorder after completing a required training and

submitting to SAMHSA a notification of intent to prescribe. This permitted the physician to

treat up to 30 patients at a time in the first year and, if requested, 100 patients at a time after that

(SAMHSA, 2016c). In July 2016, a regulation was finalized that created the possibility for some

physicians with added qualification or in specific practice settings to treat up to 275 patients at a

time. Later in 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA) amended

the Controlled Substances Act to allow qualifying nurse practitioners and physician assistants to

receive a DATA 2000 waiver and prescribe buprenorphine at the original 30 and 100 patient

limits. As discussed in the section on state laws and policies, several states have scope of

practice laws that limit the effect of this federal law. In October 2018, President Trump signed

into law the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment

(SUPPORT) Act. This law contains provisions intended to increase access to and use of MAT.

Table 3 summarizes federal prescribing restrictions that apply to alcohol and opioid use disorder

treatment. Relevant state laws or regulations are discussed in the section on state laws and

policies.

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

19

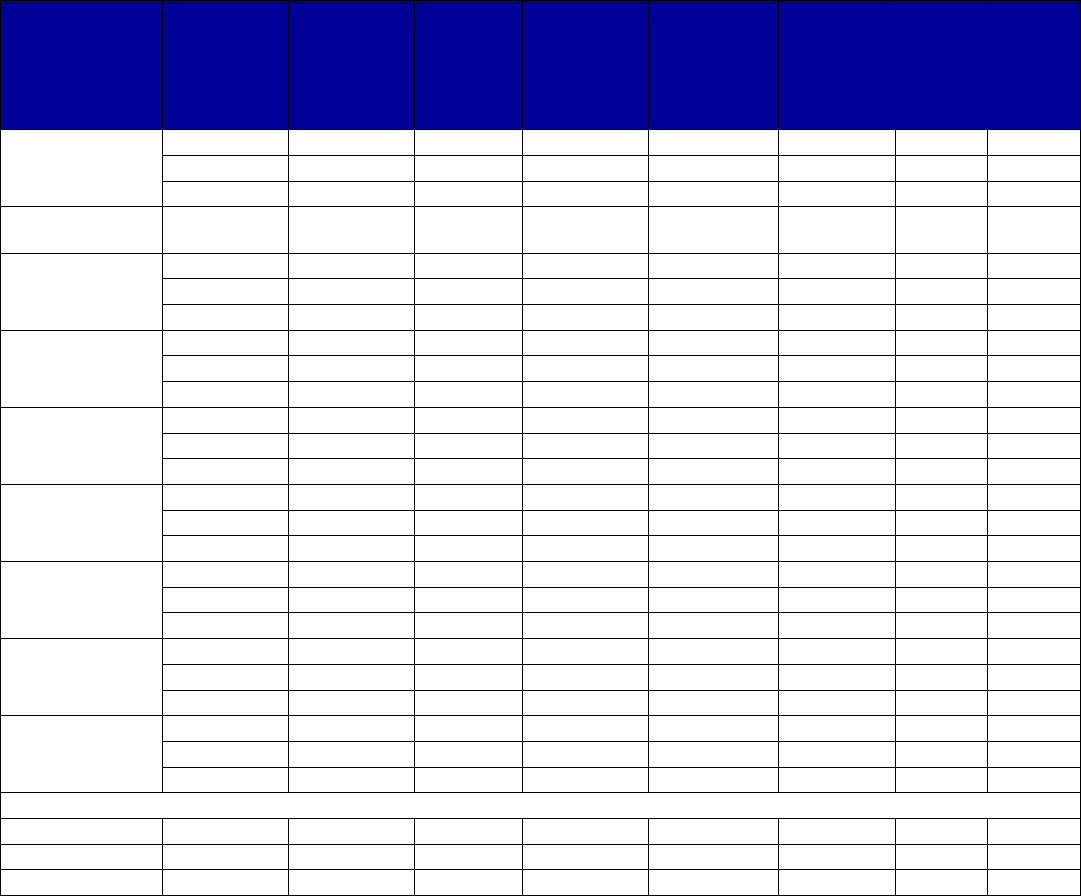

Table 3. Federal Prescribing Regulations for Medications Used to Treat Alcohol and

Opioid Use Disorders or to Reverse Opioid Overdose

Medication Federal Restrictions

Acamprosate Can be prescribed by a licensed health care professional or practitioner

Disulfiram Can be prescribed by a licensed health care professional or practitioner

Buprenorphine/

buprenorphine-naloxone

Can be prescribed by a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant

to up to 30 or 100 patients at a time after completing required training.

Some physicians with added qualification or in specific practices may treat

up to 275 patients at a time.

Methadone

Can be administered only by a SAMHSA-certified opioid treatment program

that has been registered with DEA as a narcotic treatment program

Naloxone Can be prescribed by a licensed health care professional or practitioner

Naltrexone (oral and

injectable)

Can be prescribed by a licensed health care professional or practitioner

Abbreviations: DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration.

Requirements of Parity

Additional laws and policies affect access to medications for alcohol and opioid use disorders.

The Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act

(MHPAEA) of 2008 requires that the cost sharing and treatment limitations for medications used

to treat SUDs, if covered by a health plan, must be comparable to and no more restrictive than

medications for other medical or surgical needs (Center for Consumer Information and Insurance

Oversight, 2013). These requirements apply to both quantitative and nonquantitative treatment

limits (NQTLs), which include some of the utilization management techniques commonly

applied to MAT medications (e.g., prior authorization and step therapy). Federal parity law

prohibits the use of any NQTLs for mental health or SUD benefits unless the processes,

strategies, evidentiary standards, or other factors used in applying the NQTLs to the behavioral

health benefits in the classification are comparable to, and applied no more stringently than, the

processes, strategies, evidentiary standards, or other factors used in applying the NQTLs to

medical benefits in the same benefit classification (e.g., the prescription drug benefit

classification). Thus, for example, this MHPAEA requirement is satisfied if health plans use a

tiered formulary, in which different financial requirements and treatment limits are imposed

uniformly for different tiers of drugs on the basis of factors unrelated to diagnosis, such as the

cost and efficacy of the drug (Department of the Treasury, 2013). In March 2016, the Centers

for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released a Final Rule implementing the MHPAEA

requirements for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, the Medicaid benchmark benefit

plans, and Medicaid managed care plans (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Separate but parallel regulations implement MHPAEA for nonfederal government plans with

more than 100 employees and group health plans of private employers with more than 50

employees (Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2013).

MEDICAID COVERAGE OF MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL AND OPIOID USE

DISORDERS AND OF MEDICATION FOR THE REVERSAL OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

20

States also have implemented parity laws that vary greatly regarding required coverage. As

movement occurs toward enforcement of the federal parity laws, states also are enacting statutes

and promulgating regulations designed to meet the federal requirements (National Conference of

State Legislatures, 2015; ParityTrack, n.d.).

State Laws and Policies

In addition to the state parity laws, state laws and policies may affect access to or reimbursement

of high-quality MAT in other ways. State laws fall into several categories. In a recent report on

the integration of physical and behavioral health services, with particular focus on Medicaid,

Bachrach and colleagues (2014) identified four types of statutes or regulations that may impede

the provision of integrated care, including behavioral health. These requirements included ones

related to (1) professional licensure and certification, (2) facility licensing and certification, (3)

billing requirements, and (4) data exchange (Bachrach, Anthony, & Detty, 2014). Each of these

categories of regulation may affect the provision of integrated care that includes MAT, and some

may influence the ability to provide MAT per se. Each of these requirements as well as other

state policies that may affect the provision of MAT or naloxone are addressed briefly below.

Professional Licensure and Certification

Given the shortage of physicians and, particularly, physicians approved to prescribe

buprenorphine in some areas, it is expected that treatment facilities will take advantage of the

2016 statutory and regulatory changes and turn to physician assistants or nurse practitioners to

fill the void. Individual state laws, however, may restrict whether and when a physician assistant

or nurse practitioner may prescribe medication within the scope of his or her license and the level

and type of nursing license required. State regulations may limit further whether a nurse

practitioner may prescribe controlled substances and may limit such drugs to certain schedules,

may limit the age of patients for which prescribing is allowed, may place time limits on the

prescription (e.g., 7 days), may limit prescribing setting (e.g., only inpatient), or may impose

other prescribing restrictions specifically applicable to nonphysician prescribers (American

Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2017; Stowkowski, 2016). Such limits have particularly

profound effects on the prescribing of buprenorphine, which has strict federal prescribing

restrictions that limit the availability of approved prescribers.

As discussed above, in its July 8, 2016, rulemaking, SAMHSA expanded the number of patients

to whom a waivered provider may prescribe buprenorphine (Medication Assisted Treatment for

Opioid Use Disorders, 2016). Subsequently, Congress amended the enabling statute to permit

both physician assistants and nurse practitioners to become waivered to prescribe buprenorphine

upon completion of additional instruction as part of certification (Comprehensive Addiction and

Recovery Act of 2016, 2016). As of April 2017, however, 28 states had scope of practice laws