80 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, 3, 80-100

Open Access

1874-9240/10 2010 Bentham Open

Shelter from the Storm: Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness Services

Settings

Elizabeth K. Hopper

*,1

, Ellen L. Bassuk

2,3

, and Jeffrey Olivet

4

1

The Trauma Center at JRI 1269 Beacon Street Brookline, MA 02446, USA

2

The National Center on Family Homelessness, 181 Wells Avenue, Newton, MA 02459, USA

3

Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, USA

4

Centre for Social Innovation 215 Spadina Avenue, Suite 120 Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C7, Canada

Abstract: It is reasonable to assume that individuals and families who are homeless have been exposed to trauma.

Research has shown that individuals who are homeless are likely to have experienced some form of previous trauma;

homelessness itself can be viewed as a traumatic experience; and being homeless increases the risk of further

victimization and retraumatization. Historically, homeless service settings have provided care to traumatized people

without directly acknowledging or addressing the impact of trauma. As the field advances, providers in homeless service

settings are beginning to realize the opportunity that they have to not only respond to the immediate crisis of

homelessness, but to also contribute to the longer-term healing of these individuals. Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) offers a

framework for providing services to traumatized individuals within a variety of service settings, including homelessness

service settings. Although many providers have an emerging awareness of the potential importance of TIC in homeless

services, the meaning of TIC remains murky, and the mechanisms for systems change using this framework are poorly

defined. This paper explores the evidence base for TIC within homelessness service settings, including a review of

quantitative and qualitative studies and other supporting literature. The authors clarify the definition of Trauma-Informed

Care, discuss what is known about TIC based on an extensive literature review, review case examples of programs

implementing TIC, and discuss implications for practice, programming, policy, and research.

Keywords: Homelessness, trauma, trauma-informed, systems change.

INTRODUCTION

Trauma-Informed Care: A Paradigm Shift for Homeless

Services

“Homelessness deprives individuals of…basic

needs, exposing them to risky, unpredictable

environments. In short, homelessness is more

than the absence of physical shelter, it is a

stress-filled, dehumanizing, dangerous circums-

tance in which individuals are at high risk of

being witness to or victims of a wide range of

violent events” [1].

Homelessness is a traumatic experience. Individuals and

families experiencing homelessness are under constant

stress, unsure of whether they will be able to sleep in a safe

environment or obtain a decent meal. They often lack a

stable home and also the financial resources, life skills, and

social supports to change their circumstances. In addition to

the experience of being homeless, an overwhelming

percentage of homeless individuals, families, and children

have been exposed to additional forms of trauma, including:

neglect, psychological abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse

during childhood; community violence; combat-related

*Address correspondence to this author at the Trauma Center at JRI 1269,

Beacon Street Brookline, MA 02446, USA; Tel: (617) 232-1303, Ext.

211; E-mail: ehopper@jri.org

trauma; domestic violence; accidents; and disasters. Trauma

is widespread and affects people of every gender, age, race,

sexual orientation, and background within homeless service

settings.

Early developmental trauma—including child abuse,

neglect, and disrupted attachment—provides a subtext for

the narrative of many people’s pathways to homelessness

[2]. Violence continues into adulthood for many people, with

abuse such as domestic violence often precipitating

homelessness [3-5], and with homelessness leaving people

vulnerable to further victimization. The impact of traumatic

stress often makes it difficult for people experiencing

homelessness to cope with the innumerable obstacles they

face in the process of exiting homelessness [6], and the

victimization associated with repeated episodes of

homelessness. Research has found that people who

experienced repeated homelessness were more likely than

people with a single episode of homelessness to have been

abused, often during childhood [6].

Trauma refers to an experience that creates a sense of

fear, helplessness, or horror, and overwhelms a person’s

resources for coping. The impact of traumatic stress can be

devastating and long-lasting, interfering with a person’s

sense of safety, ability to self-regulate, sense of self,

perception of control and self-efficacy, and interpersonal

relationships. Some people have minimal symptoms after

trauma exposure or recover quickly, while others may

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 81

develop more significant and longer-lasting problems such

as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex

Trauma.

Trauma reactions are not the only psychiatric issue facing

people who are homeless; many people experiencing

homelessness also suffer from depression, substance abuse [7-

10], and severe mental illness [8, 10]. These issues leave

individuals even more vulnerable to revictimization [11],

interfere with their ability to work, impair their social networks

[8], and further complicate their service needs.

These findings suggest that we will be unable to solve the

issue of homelessness without addressing the underlying trauma

that is so intricately interwoven with the experience of

homelessness. Those working in homeless services have the

opportunity to reach many trauma survivors who are otherwise

overlooked. Providers in these settings address the immediate

crisis by offering food, shelter, and clothing; but they can also

contribute to longer-lasting changes by helping an individual or

family develop supportive connections in the community and

begin to heal from past traumas. Despite this fact, few programs

serving homeless individuals and families directly address the

specialized needs of trauma survivors. Homeless services have a

long history of serving trauma survivors, without being aware

of or addressing the impact of traumatic stress [12].

Overwhelmed by the daily needs of their clients, providers in

these settings often have few resources to address issues of

long-term recovery.

With increasing recognition of the pervasiveness of

traumatic stress among people experiencing homelessness,

awareness is growing of the importance of creating Trauma-

Informed Care within homeless services settings. Trauma-

Informed Care (TIC) involves “understanding, anticipating, and

responding to the issues, expectations, and special needs that a

person who has been victimized may have in a particular setting

or service. At a minimum, trauma-informed services endeavor

to do no harm—to avoid retraumatizing or blaming [clients] for

their efforts to manage their traumatic reactions” [13].

Implementing TIC requires a philosophical and cultural shift

within an agency, with an organizational commitment to

understanding traumatic stress and to developing strategies for

responding to the complex needs of survivors.

Despite its importance, the implementation of TIC within

homelessness service settings is still in its infancy. Currently,

the nature of TIC remains ill-defined. Strategies for

implementation are obscure, few program models exist, and

there is limited communication and collaboration among

programs implementing TIC. The descriptive and research

literature in this area is sparse, with only a handful of studies

examining the nature and impact of TIC. More clarification is

needed about what exactly defines TIC, what changes should be

made within systems wishing to offer TIC, and how these

changes should be implemented.

The purpose of this paper is to review the evidence base that

supports the use of TIC for individuals and families

experiencing homelessness. In this review, we have attempted

to:

• Establish a consensus-based definition of TIC

• Discuss what is known about TIC based on our literature

review

• Describe models and case examples of what is being

done in the field to implement TIC within homeless

service settings

We conclude by summarizing implications of our current

state of knowledge for practice, programming, policy, and

research and by highlighting next steps for developing

evidence-based, trauma-informed homeless services.

What is Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)?

What is meant by TIC? Although there is agreement that

“trauma-informed” refers generally to a philosophical/ cultural

stance that integrates awareness and understanding of trauma,

there is no consensus on a definition that clearly explains the

nature of TIC.

TIC supports the delivery of Trauma-Specific Services

(TSS). TSS refers to interventions that are designed to directly

address the impact of trauma, with the goals of decreasing

symptoms and facilitating recovery. TSS differs from TIC, in

that TSS are specific treatments for mental disorders resulting

from trauma exposure, while TIC is an overarching framework

that emphasizes the impact of trauma and that guides the

general organization and behavior of an entire system. TSS may

be offered within a trauma-informed program or as stand-alone

services [12].

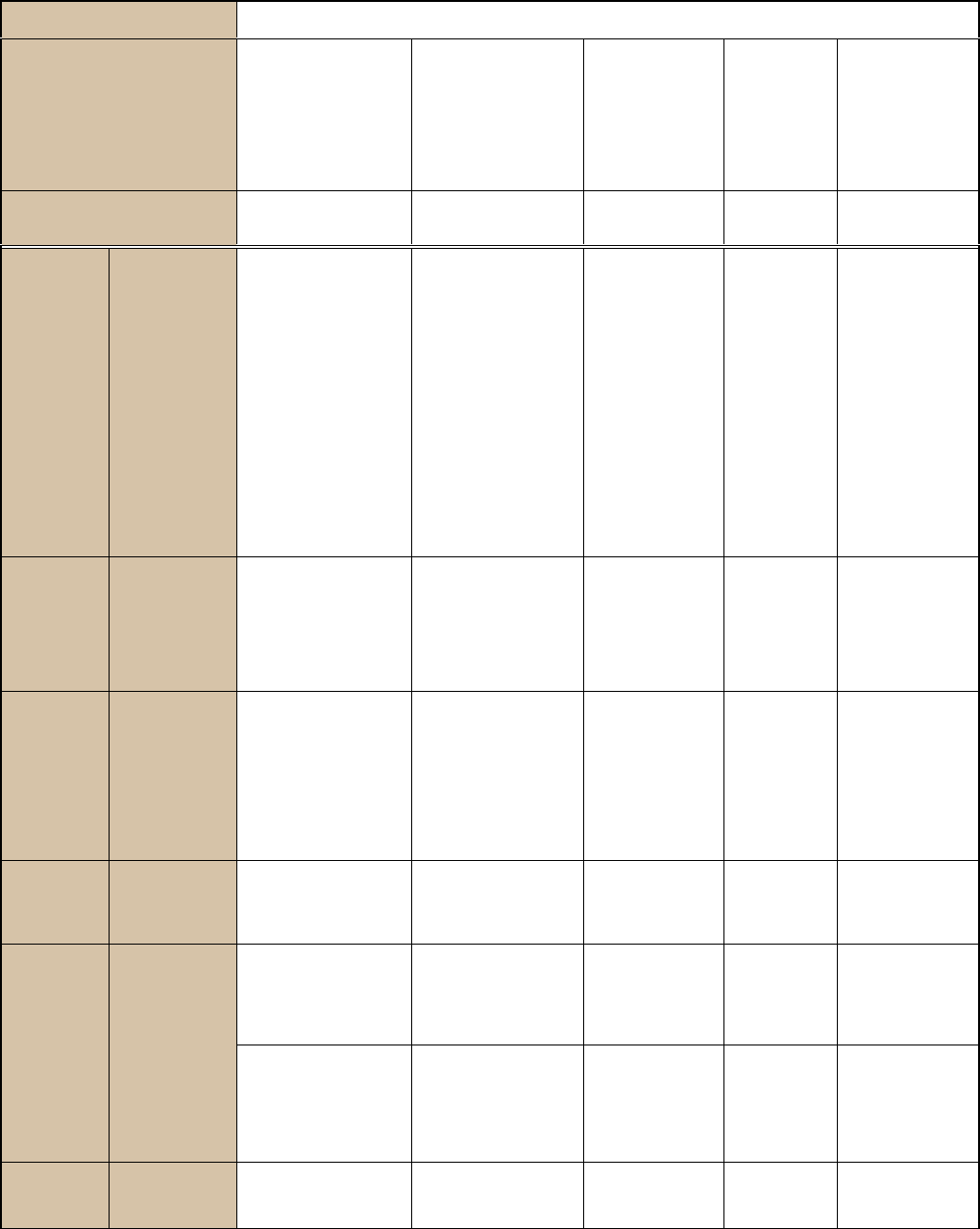

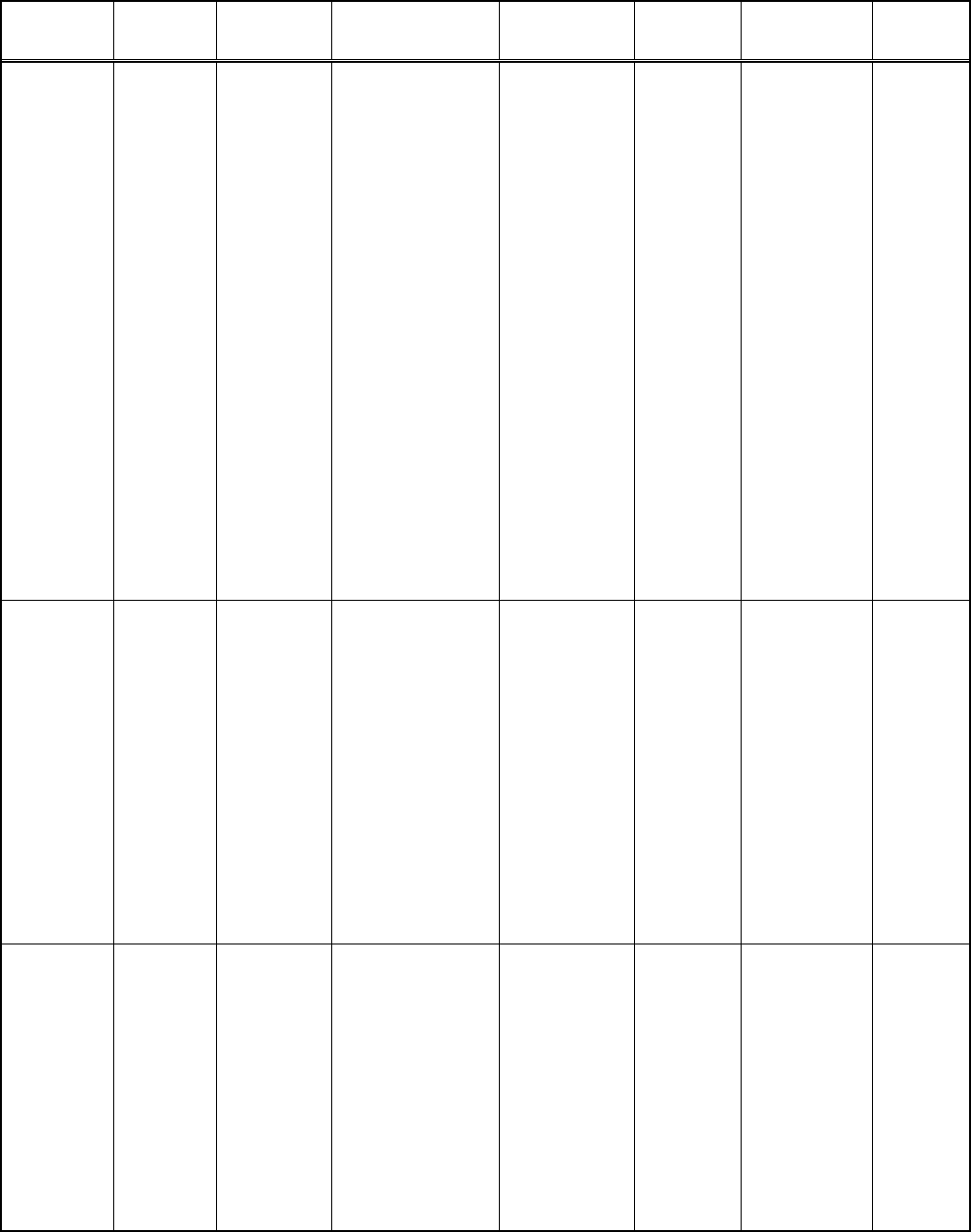

Based on the literature review, we summarized the basic

principles of TIC proposed by various workgroups,

organizations, expert panels, and researchers. (see Table 1).

Each of these sources posited a unique definition of TIC. We

identified and highlighted common cross-cutting themes and

then synthesized them into a single definition. Themes include:

• Trauma awareness: Trauma-informed service

providers incorporate an understanding of trauma into

their work. This may involve altering staff perspectives,

with providers understanding how various symptoms

and behaviors represent adaptations to traumatic

experiences. Staff training, consultation, and supervision

are important aspects of organizational change towards

TIC and organizational practices should be modified to

incorporate awareness of the potentially devastating

impact of trauma. For example, agencies may implement

routine screening for histories of traumatic exposure,

may conduct routine assessments of safety, and may

develop strategies for increasing access to trauma-

specific services. Dealing with vicarious trauma and

self-care is also an essential ingredient of trauma-

informed services. Many providers have experienced

trauma themselves and may be triggered by client

responses and behaviors.

• Emphasis on safety:

Because trauma survivors often

feel unsafe and may actually be in danger (e.g., victims

of domestic violence), TIC works towards building

physical and emotional safety for consumers and

providers. Precautions should be taken to ensure the

physical safety of all residents. In addition, the

organization should be aware of potential triggers for

consumers and strive to avoid retraumatization. Because

interpersonal trauma often involves boundary violations

and abuse of power, systems that are aware of trauma

dynamics should establish clear roles and boundaries

that are an outgrowth of collaborative decision-making.

82 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

Privacy, confidentiality, and mutual respect are also

important aspects of developing an emotionally safe

atmosphere. Additionally, cultural differences and

diversity (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation) must

be addressed and respected within trauma-informed

settings.

• Opportunities to rebuild control: Because control is

often taken away in traumatic situations, and because

homelessness itself is disempowering, trauma-

informed homeless services emphasize the

importance of choice for consumers. They create

predictable environments that allow consumers to re-

build a sense of efficacy and personal control over

their lives. This includes involving consumers in the

design and evaluation of services.

• Strengths-based approach: Finally, TIC is

strengths-based, rather than deficit-oriented. These

service settings assist consumers to identify their own

strengths and develop coping skills. TIC service

settings are focused on the future and utilize skills-

building to further develop resiliency.

These principles form a standard for programs wishing to

develop TIC within homeless service settings. Based on

these combined principles, we developed a consensus-based

definition of TIC:

Consensus-Based Definition

“Trauma-Informed Care is a strengths-based

framework that is grounded in an understanding of

and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that

emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional

safety for both providers and survivors, and that

creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a

sense of control and empowerment.”

Trauma-informed approaches are designed to respond to

the impact of trauma. The principles described above target

the specialized needs of trauma survivors and describe how

services can be delivered through the lens of trauma.

METHODS

This paper reviews the evidence base supporting the

effectiveness of TIC for people experiencing homelessness. To

date, most determinations of what constitutes evidence-based

practice have relied on outcome-based quantitative research.

However, this approach neglects qualitative analyses that

examine the nature and process of the intervention, as well as a

wealth of information that reflects what is occurring in practice.

In fact, corroborative evidence, including clinical wisdom about

“what works,” is often the starting point for developing both

qualitative and quantitative studies. In the homelessness field,

corroborative evidence may be the primary body of knowledge

we have about a particular intervention.

For this review, we utilized a comprehensive framework

tha

t was developed by the Homelessness Resource Center

(HRC) for assessing the level of evidence of an emerging,

promising or best practice [15]. The goal of this framework is

not to decide whether a practice qualifies as evidence-based, but

rather to synthesize all that we currently know about the

intervention. Thus, our review included peer-reviewed

quantitative and qualitative studies, as well as corroborative

literature (e.g., program evaluations and unpublished pilot

studies).

The literature on TIC is significantly greater in mental health

and substance use fields than within the homelessness field.

Thus, we also reviewed the current evidence base for trauma-

informed practices in these areas since there is a large overlap in

the difficulties faced by many individuals with mental

health/substance use issues and those in homeless service

settings. In fact, in the Women, Co-Occurring Disorders, and

Violence Study (WCDVS), a large multi-site study examining

trauma-informed services for women with co-occurring

disorders and trauma exposure, 70.4% of participants had been

homeless at some point in their lives [16]. We reviewed

evidence for trauma-informed services within all these settings,

applying this broader knowledge base to our understanding of

TIC within homeless service settings.

We conducted our literature review by searching two

databases, PsycInfo and Medline (PubMed), for peer-reviewed

articles published in major journals. In addition, we used the

Google search engine to locate web-based literature and

program information. Our search terms included: homeless,

homelessness, housing, shelters, trauma, trauma-informed,

PTSD, services, abuse, violence, domestic violence,

psychological, substance use, and mental health. We also

completed more specialized searches on unique populations

(using search terms such as youth, men, ethnicity, veterans),

authors of note (e.g., Harris, Fallot, Bassuk, and van der Kolk),

models (e.g., Attachment, Self-Regulation and Competency

[ARC] and Sanctuary), programs (e.g., Community

Connections, the STAR program, and the Community Trauma

Treatment Center for Runaway and Homeless Youth), and

research studies (e.g., the Women, Co-Occurring Disorders, and

Violence Study).

In addition to reviewing the literature, we contacted various

programs directly, by telephone or email, including: the Natio-

nal Center on Family Homelessness (Moses, Guarino); Home-

lessness Resource Center (Olivet); Community Connections

(Fallot); the Institute for Health and Recovery (Markoff &

Dargon-Hart); CT State Department of Mental Health and

Addiction Services (Leal); the Domestic Violence & Mental

Health Policy Initiative (Brashler, Hall); the Community

Trauma Treatment Center for Runaway and Homeless Youth

(Schneir); the Trauma Center at JRI/ Youth on Fire, developers

of Phoenix Rising (Spinazzola); Kinniburgh and Blaustein,

developers of ARC; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical

Center, developers of CARE (Pearl); University of Connecticut

Department of Psychology and the CT Department of Mental

Health and Addiction Services Research Division (Marra). Many

of these programs sent unpublished program evaluation reports,

manuals, or self-assessment tools, for inclusion in this review.

RESULTS

Organizational Needs Assessments: Do We Need

Trauma-Informed Care?

Needs assessments can be used to identify needs and to

detect gaps in service within a system. We began by

reviewing results of needs assessments conducted by several

agencies regarding the relevance of trauma within their

service system and the need for TIC. These needs

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 83

Table 1. Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

Example Definitions of Trauma-Informed Care

Common Principles Across

Definitions

Community

Connections: Five

Guiding Principles for

Trauma-Informed

Services [12]

NASMHPD*: Criteria

for Building a Trauma-

Informed Mental

Health Service System

NCTSN**:

Principles of

Trauma-Informed

Care for Children

NCFH***:

Operating

Principles for

Trauma-

Informed

Organizational

Self-

Assessment

WCDVS****:

Trauma-Informed

or Trauma-

Denied: Principles

& Implementation

of Trauma-

Informed Services

for Women [14].

Consensus-Based Principles

Across Definitions

Theory-Based Expert Trauma Panel Experts

Theory-Based

Research-based

1. Trauma

Awareness

a. Program

philosophy and

mission

Trauma function/ focus,

trauma policy or

position, financing for

best practices, trauma-

informed services,

clinical practice

guidelines for people

with trauma histories,

trauma-informed disaster

planning, systems

integration, research &

data on trauma &

evidence-based & best-

practice treatment

models, access to

evidence-based & best-

practice trauma treatment

Tra

uma

awareness;

basic

understanding

of trauma &

triggers;

includes staff

training &

supervision,

educating

consumers

about trauma

Recognize the

impact of trauma on

development and

coping

b. St

aff

education,

training, and

consultation

Wo

rkforce orientation,

training, support,

competencies and job

standards related to

trauma; promote

education of

professionals in trauma

E

mphasize trauma

recovery as a

primary goal

c.

Practices

Trauma screening and

assessment; Trauma-

specific services,

including evidence-based

and emerging best-

practice treatment

models

Integration

(symptoms

such as

adaptive

coping,

integrating

services,

trauma-specific

services)

d. Recognition of

vicarious trauma

and staff self-

care

2. Safety

a. Physical and

emotional safety

Safety (physical and

emotional)

M

aintaining clear

and consistent

boundaries

Safety, basic

needs,

consistency,

and

predictability

Create an

atmosphere of

safety, respect, and

acceptance

b. Relationships:

authentic,

respectful, clear

boundaries

Trustworthiness (clear

tasks, consistent

practices, staff-consumer

boundaries)

[

see Delivering

services below]

Engagement:

respectful

nonjudgmental

relationships,

clear

boundaries

Utilize a relational

collaboration model.

Growth is fostered

by mutual,

respectful, authentic

relationships

c. Avoid

retraumatization

Procedures avoid

retraumatization and

reduce impacts of trauma

Minimize

retraumatization

84 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

assessments were generally designed as a first step, prior to

initiating a more formal organizational self-assessment or to

beginning programmatic shifts. Several findings emerged

from a review of these needs assessments:

• Providers feel that they need to be better informed

about trauma and violence [17, 18]. Directors and staff

within state domestic violence coalitions reported that

many shelters are unprepared to deal with the complex

needs of the women they serve, many of whom have

few resources and have been victimized as children and

as adults. Domestic violence advocates reported an

increasing awareness of the need for services appropriate

for women with mental health issues, substance abuse

problems, and histories of abuse. They also expressed a

need for guidance and resources in improving their

responses to survivors of domestic violence who have

experienced multiple abuses throughout their lives [18].

A multi-site program implementing trauma-informed

services found that prior to implementation, sites had

little knowledge about trauma, how to facilitate

recovery, or how services might help or retraumatize

survivors [19].

• Many providers do not have systematic ways of

assessing for trauma-related issues. In a study

examining PTSD screening and referral practices in VA

addiction treatment programs, they found that although

one-half to two-thirds of clinicians did routinely screen

for trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms,

assessments were generally not conducted system-

atically and did not utilize validated measures [20].

• Consumers want services that are empowering.

Qualitative research has suggested that homeless

individuals and families need and want trauma-informed

services, including desire for autonomy, prevention of

further victimization, and assistance in restoring their

devalued sense of identity [21]. A provider guidebook,

written from a consumer perspective, notes the need

for accessible and effective programs for trauma

survivors [22].

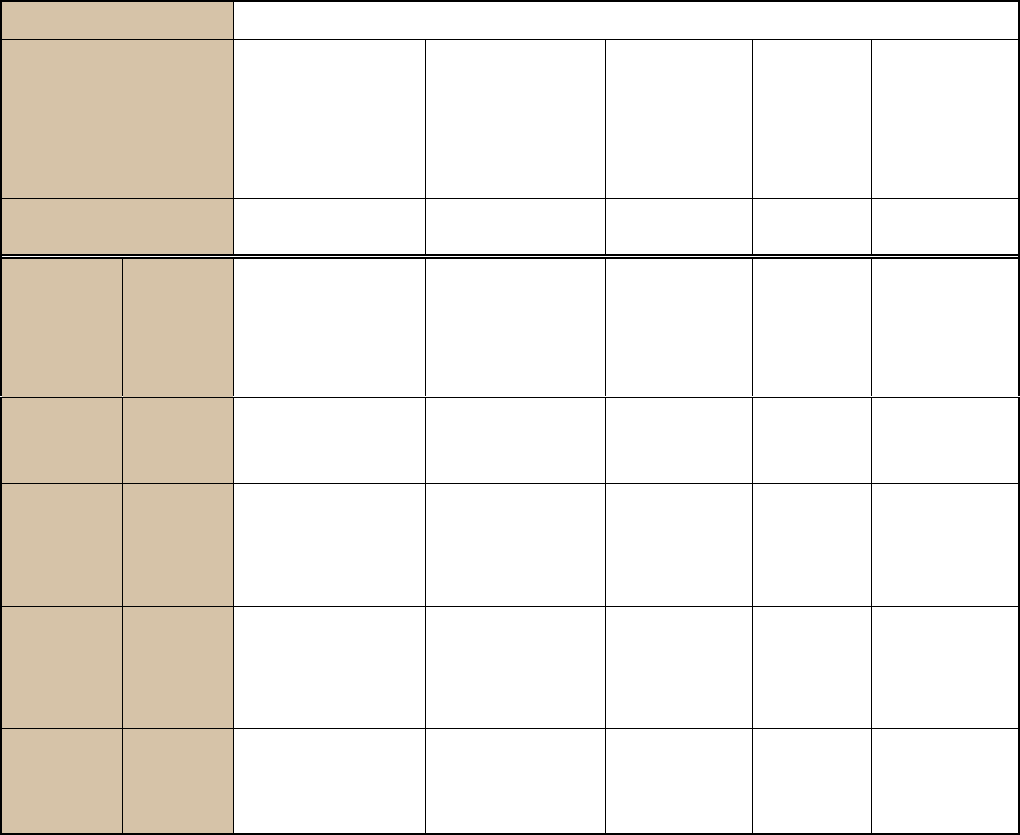

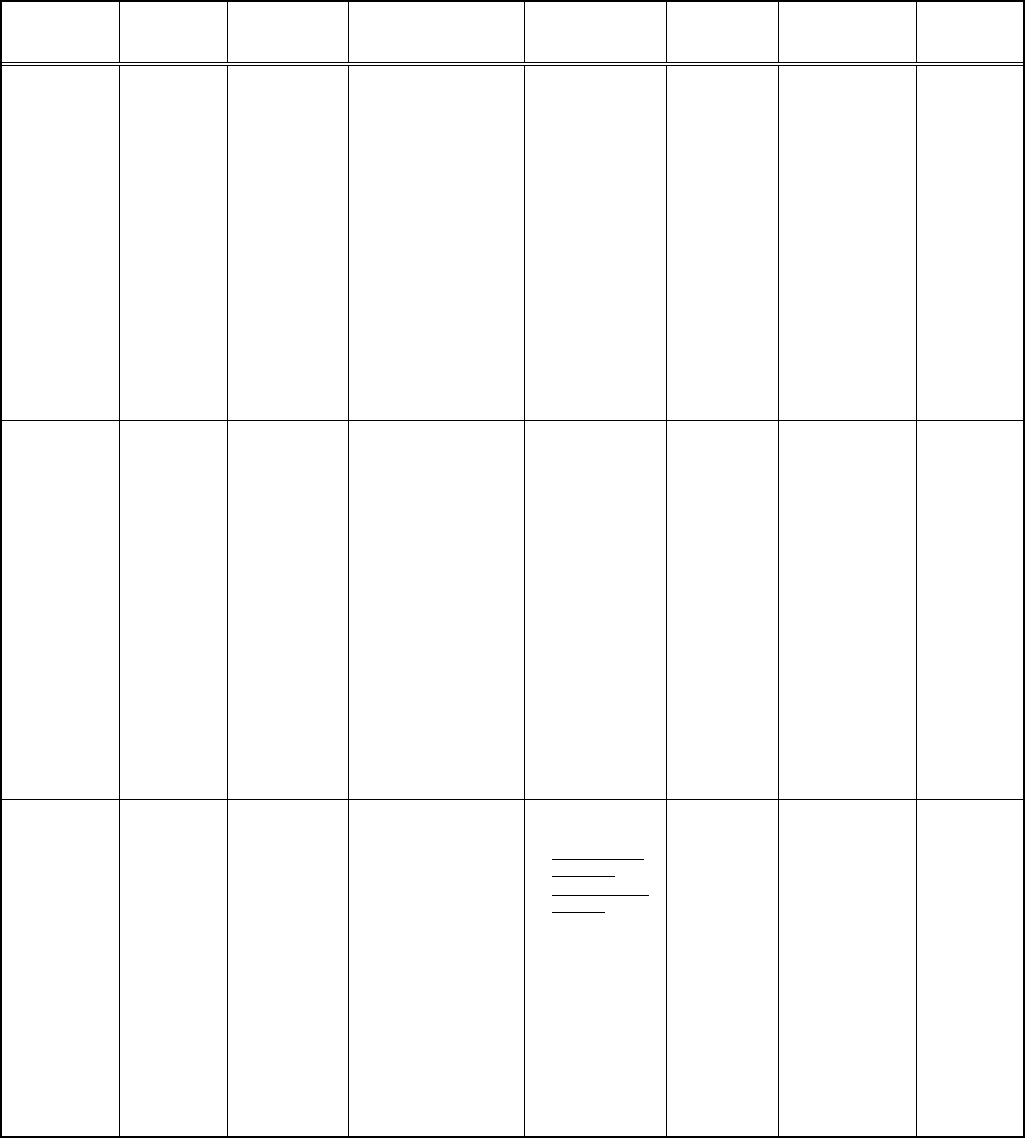

(Table 1) contd…..

Example Definitions of Trauma-Informed Care

Common Principles Across

Definitions

Community Connections:

Five Guiding Principles

for Trauma-Informed

Services [12]

NASMHPD*: Criteria

for Building a Trauma-

Informed Mental

Health Service System

NCTSN**:

Principles of

Trauma-Informed

Care for Children

NCFH***:

Operating

Principles for

Trauma-

Informed

Organizational

Self-

Assessment

WCDVS****:

Trauma-Informed

or Trauma-

Denied: Principles

& Implementation

of Trauma-

Informed Services

for Women [14].

Consensus-Based Principles

Across Definitions

Theory-Based Expert Trauma Panel Experts

Theory-Based

Research-based

d. Acceptance

of and respect

for diversity

Trau

ma policies and

services that respect

culture, race, ethnicity,

gender, age, sexual

orientation, disability,

and socio-economic

status

Delivering services

in a nonjudgmental

and respectful

manner

Cultural

competence

Work towards

cultural competence,

understand

contextual factors

3. Choice &

Empowerment

a. Choice and

control

Choice: maximize

consumer choice and

control

Consumer/Trauma

Survivor/ Recovering

person involvement and

trauma-informed rights

Maximizing choice

and control for

participants

Consumer

control, choice

and autonomy

Underscore

consumers’ choice

and control over

recovery

b.

Emp

owermen

t model

Empowerment: prioritize

consumer empowerment,

skill-building, and growth

Avoidi

ng

provocation and

power assertion

Open

communication:

provide

information

openly to

consumers

Use an

empowerment

model

c. Consumers

involved in

service

development

and

evaluation

Collaboration: maximize

collaboration and sharing

of power between staff and

consumers

Sharing power in

the running of

shelter activities

Shared power

and governance

Involve consumers

in design and

evaluation of

services

4. Strengths-

based

Focus on

strengths,

resiliency

[see Empowerment above]

Hea

ling,

instilling hope

Highlight

consumers’

strengths,

adaptations, and

resiliencies

* NASMHPD= National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

** NCTSN = National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

*** NCFH = National Center on Family Homelessness.

**** WCDVS = Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Study.

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 85

• Mental health services are an important need for

many homeless families and individuals. In a multi-

site research study on trauma-informed services for

homeless families, researchers examined current service

needs, including families’ need for social capital

(educational or employment-related interventions),

physical health, and mental health/substance use

treatment. Among the families, they found that “mental

health needs were the most prevalent of all the

intervention needs components across sites (62%),” with

many facing multiple challenges, signaling the need for

comprehensive intervention [23].

The results of these needs assessments supported the central

importance of dealing with trauma within homelessness service

settings and the perceived need for TIC.

Trauma-Informed Care within Homelessness Services

Settings: Attitudes, Implementation, and Outcomes

Once the perceived need for trauma services is established,

we can begin to explore the development of a TIC framework

within homelessness service settings. We reviewed available

quantitative, qualitative, and corroborative evidence regarding

trauma-informed services.

Prochaska’s stages of change model [24] highlights the fact

that change is a process for individuals, who progress through

precontemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance of

change. Similarly, systems change is a multi-step process. Our

review of the literature highlighted three areas of evidence:

attitudes, implementation, and outcomes. “Attitudes” refers to

the beliefs of consumers and providers (at all levels, from

management to front-line workers) of the need for a paradigm

shift, confidence in ability to institute a paradigm shift, and

belief that such a shift will lead to positive outcomes.

“Implementation” coincides with Prochaska’s action stage of

change. It is a process variable, and is concerned with how

changes are made. Implementation requires a clear definition of

what is meant by Trauma-Informed Care, in order to translate

these principles into concrete changes that will be instituted

within the system. Finally, “outcomes” refers to the impact of a

paradigm shift to TIC within homelessness service settings.

Measurable objectives help to assess the efficacy of systems

change. Outcomes may include measurable quantitative

outcomes, such as a decrease in recidivism in homelessness, or

qualitative outcomes, such as self-esteem or satisfaction with

services.

Review of the Evidence: What Do We Know About TIC?

In our review of the evidence for TIC, several salient points

emerged:

1. Attitudes

• Programs attempting to implement TIC have

encountered some concerns and resistance on the

part of providers. Providers may be afraid that

addressing trauma will open a “Pandora’s box” of

reactions. They may lack confidence in their ability to

manage and address trauma reactions and may be

concerned that they will encounter triggers of their own

trauma histories [19]. They may also worry that they

will not have the resources to adequately respond to the

complex needs of survivors.

• Because of these concerns, taking the time to build

“buy

-in” is particularly important. Recognizing the

importance of commitment in organizations, some

programs have developed committee structures

geared towards obtaining “buy-in” from

administration, program staff, and consumers.

Building strong relationships also aided buy-in and

integration of services [19]. After building agency-

wide commitment, programs have found strong

support from staff members for implementing a

trauma-informed model [25].

• Consumers want providers who are empathic and

caring, who provide validation, and who offer

emotional safety—characteristics of trauma-

informed providers. Consumers have emphasized

the benefits of working with trauma-informed

providers. Some have suggested that programs could

benefit from having more trauma services, that

practitioners need to remain patient, and that

consumers themselves need to be invested in actively

addressing their own issues [26]. However, even

within trauma-informed systems, consumers

sometimes struggle to feel empowered within a larger

service system [27].

2. Implementation

• Training is central to implementing TIC. The

majority of programs working to build TIC utilized

staff training to increase awareness of and sensitivity

to trauma-related issues. A large multi-site study of

trauma-informed models found that “training on

trauma for non-trauma providers was the first and

most important step in making services more trauma-

informed” [19].

• Ongoing supervision, consultation, and support

are needed to reinforce trauma-based concepts.

One lesson from WCDVS was the importance of

ongoing supervision and support to ensure that the

environment is trauma-informed and that staff

members practice appropriate self-care. Many

programs also used external trauma consultants and

ongoing training to reinforce knowledge and

commitment to building trauma-informed services

[19].

• Assessment and screening are important aspects of

trauma-informed services. Research documenting

high prevalence rates of trauma among people

experiencing homelessness has led to the conclusion

that screening for trauma is important within

homeless service settings [28]. Although providers

have at times expressed concern that inquiring about

trauma histories will lead to traumatic stress

responses, findings indicate that there are few adverse

reactions to screening and assessment. Instead, most

people benefit from this type of assessment [29].

Several pilot studies show that providers refined their

intake processes to include screening for trauma

exposure [28, 30]. Additionally, screening and

assessment tools should be revised and refined with

consumer and provider feedback [29].

86 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

• Because homeless individuals often have a

multitude of service needs, comprehensive and

integrated services are essential. Studies have found

that service settings offering integrated counseling—

addressing trauma, mental health, and substance use

issues—had better results than settings that were not

integrated [31].

• Integrating trauma-informed services for children

is

also important. Children of parents who are

dealing with trauma, mental illness, substance abuse,

and/or homelessness may be at greater risk for

adverse outcomes. A number of programs working to

integrate trauma-informed services have also

highlighted the importance of parallel services for

children. In WCDVS, a subset of sites offered

specialized children’s programs, including

assessment, groups, and resource

coordination/advocacy for children to build coping

skills, strengthen interpersonal relationships, and

develop positive identity and self-esteem [32].

• Many factors challenge implementation of

trauma-informed services. Various reports

highlighted the logistical difficulties of systems

change. Change, especially within larger systems, can

be time-consuming and requires a great deal of

commitment across all levels of an organization.

Organizational resistance and stress can be a barrier

to larger systems change [33]. Moses highlighted

challenges to systems change across a number of sites

working to implement integrated, trauma-informed

services for women with co-occurring disorders.

These challenges included philosophical differences

between mental health and substance use treatment

approaches, differences around issues of trauma,

resistance at the service and administrative levels,

limited resources, difficulties in achieving consistent

participation in trauma groups, staff turnover, and the

difficulty of change in general [13].

• Implementing a trauma-informed model can lead

to changes in how an organization functions. In a

program implementing a trauma-informed model,

staff reported a number of changes within their

programs, including increased awareness and

sensitivity about trauma, intake that incorporates

questions about trauma, more freedom and choice

given to consumers regarding their treatment, and

environmental changes that led to increases in safety,

confidentiality, and a more welcoming atmosphere

[30].

• Including consumers in developing and evaluating

trauma-informed services is important. Although

there has not yet been research that examines

differences in services that include or do not include

consumers in program development and evaluation,

current wisdom in the field stresses the importance of

including consumers in all aspects of programming

[34, 35]. This wisdom is consistent with theories on

empowerment, which suggest that survivors should

be given agency in effecting their own outcomes [36].

The WCDVS found that integrating consumers into

the design and evaluation of services had a profound

impact on the systems involved [19], and that

“integral to the… group's personal and professional

growth was the development and expression of their

individual and collective voices” [27].

• Cultural competence is important in developing

TIC. Because trauma may have different meanings in

different cultures, and because traumatic stress may

be expressed differently within different cultural

frameworks, it is important for providers within a

trauma-informed system to work towards developing

cultural and linguistic competence [13].

3. Outcomes

• Trauma-informed service settings, with trauma-

specific services available, have better outcomes

than “treatment as usual” for many symptoms. We

know from a variety of studies [31, 37] and pilot

programs [38] that setting that utilize a trauma-

informed model report a decrease in psychiatric

symptoms and substance use. Some of these programs

have shown an improvement in consumers’ daily

functioning and a decrease in trauma symptoms,

substance use, and mental health symptoms. These

findings suggest that integrating services for trau-

matic stress, substance use, and mental health leads to

better outcomes [16].

• TIC for children lead to better outcomes, such as

better self-esteem, improved relationships, and

increased safety. A subset of programs within

WCDVS examined the impact of a standardized,

trauma-informed intervention for children, consisting

of a clinical assessment, coordination of resources

and advocacy, and a psycho-educational skills-

building group. One year later, children in the

intervention group had more positive self-identity,

increased tools for building healthy relationships, and

improved safety. These changes were particularly

striking for children who had witnessed violence [32,

39].

• Early indications suggest that TIC may have a

positive effect on housing stability. A multi-site

study of TIC for homeless families found that, at 18

months, 88% of participants had either remained in

Section 8 housing or moved to permanent housing

[23]. An outreach and care coordination program that

provided family-focused, integrated, trauma-informed

care to homeless mothers in Massachusetts found that

the program led to increased residential stability [38].

• TIC may lead to a decrease in crisis-based

services. Some studies have found decreases in the

use of intensive services such as hospitalization and

crisis intervention following the implementation of

trauma-informed care [40].

• Trauma-informed, integrated services are cost-

effective. Because trauma-informed integrated

services have improved outcomes but do not cost

more than standard programming, they are judged to

be cost-effective [41].

•

Qua

litative results find that providers report

positive outcomes in their organizations from

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 87

implementing TIC. Providers report greater

collaboration with consumers, enhanced skills, and a

greater sense of self-efficacy among consumers, and

more support from their agencies. Supervisors report

more collaboration within and outside their agencies,

improved staff morale, fewer negative events, and

more effective services [40].

• Qualitative results indicate that consumers

respond well to TIC. Within the D.C. Trauma

Collaboration study, consumers reported an increased

sense of safety, better collaboration with staff, and a

more significant “voice.” Eighty-four % of consumers

rated their overall experience with these trauma-

informed services using the highest rating available

[42]. Survey results suggest that consumers were very

satisfied with trauma-informed changes in service

delivery [25].

These results reinforce the need for TIC, assist in further

defining TIC, clarify the process of implementation, and

suggest the efficacy of TIC for certain outcomes. However,

in our review, we found that various questions were not

addressed by available evidence. These gaps in the available

evidence are important in highlighting the additional work

that remains to be done to implement TIC in homelessness

service settings.

Review of the Evidence: What Do We Not Know About

TIC?

Our review of the literature highlighted several directions

for future exploration:

1. Attitudes

• Although providers and consumers alike generally

pay lip service to the idea of TIC, we do not know

the extent to which their attitude is influenced by

demand. In much of the research to date, providers

and consumers were given brief questionnaires or

were interviewed—in many cases, by the individuals

working to build trauma-informed services. Thus,

there may be a tendency to indicate support of

implementation plans and strategies in the absence of

true commitment.

2. Implementation

• We do not know exactly what constitutes “trauma-

informed care.” Trauma has become a buzz-word

recently, with many agencies and workgroups noting

the importance of becoming “trauma-informed.”

However, definitions of “trauma-informed” and how

these ideas are implemented vary widely. There is

generally a lack of specificity in how agencies are

defining “trauma-informed,” and how this relates to

actual practice.

• We do not have a clear method for measuring the

degree to which a program is trauma-informed.

Because of the lack of definitions and behaviorally-

defined changes signifying trauma-informed services,

there is no consistent basis for identifying whether or

not and to what degrees a program is trauma-

informed.

• We do not know how special populations respond

to trauma-informed homelessness services. Much

of the evidence on trauma-informed homelessness

systems concerns women and children. We know less

about the response of other groups, such as men,

veterans, individuals from ethnic/racial minorities or

other cultures, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and

transgendered (LGBT) individuals.

3. Outcomes

• We do not know whether differences in outcomes

are based on trauma-informed environments,

trauma-specific interventions, or both. Because

many service settings that provide TIC also offer

trauma-specific services, the extent to which each

component contributes to change is difficult for

research studies to determine.

• We do not know whether trauma-informed

services are effective specifically within homeless

services. Although the research in other fields

suggests that trauma-informed services may be

effective for homeless individuals, there have yet to

be any rigorous, quantitative studies exploring

outcomes within homelessness service settings. The

results of the Homeless Families Program, a current

multi-site evaluation of trauma-informed

homelessness services, may begin to shed some light

on this issue.

Our review of the current evidence suggests that TIC is

an i

mportant area for further exploration. Initial feedback

appears to support the assertion that TIC has a positive

impact on both the process and outcome of service provision

within homelessness service settings. However, the review

highlighted as many questions and gaps as it defined results

and conclusions.

Because the implementation of TIC within homelessness

service settings is in its infancy, it is particularly important to

review lessons from the field, including self-assessments and

frameworks that are being developed to guide the paradigm

shift to TIC, as well as feed back from local, regional, and

national programs and initiatives that are implementing TIC.

Lessons from the field highlight clinical insights, new

practice initiatives, and areas in need of further qualitative

and quantitative research.

Corroborative Evidence: Lessons from the Field on

Building TIC in Homelessness Service Systems

When we look to the field for best practices and clinical

wisdom, we find a wealth of information about current

theories, practices, programming, and policy initiatives. This

information tells us that although we do not yet have

substantial outcome-based research supporting the

effectiveness of TIC, there is considerable activity in the

field that is awaiting additional documentation. Many

homeless service systems are beginning to address this

issue—administrators, providers, consultants, and consumers

are working together to transform programs into

environments that offer TIC.

After recognizing the pervasiveness of traumatic stress

among people experiencing homelessness, various programs

are taking steps to become more trauma-informed. We have

88 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

selected several case examples to describe the ways in which

homeless service settings are striving to become more

trauma-informed. This is not a comprehensive list of trauma-

informed resources and programs. Instead, it is intended to

illustrate various creative ways that programs are

implementing trauma-informed models within homeless

service systems, and some of the tools that are available to

aid this transition.

Selected Promising Models

T

o foster the development of trauma-informed homeless

service settings without reinventing the wheel within each

individual program, innovators have developed frameworks

and models that can serve as guides for implementing TIC.

Various models have been proposed that support

organizational change towards a model of TIC and that guide

trauma-informed service delivery. Some of these models are:

• Attachment, Regulation, and Competency: A

Comprehensive Framework for Intervention with

Complexly Traumatized Youth (ARC) [43]

• Child Adult Relationship Enhancement (CARE)

• A Long Journey Home [44]

• Phoenix Rising [45]

• Sanctuary Model [46]

• Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems

[12]

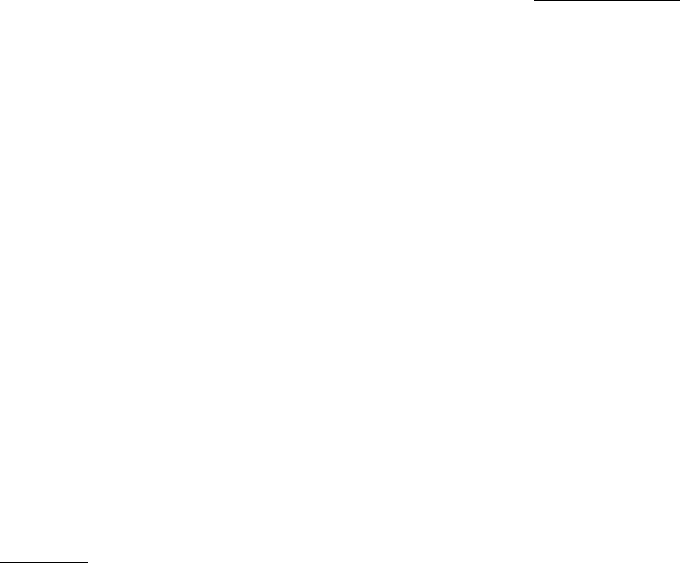

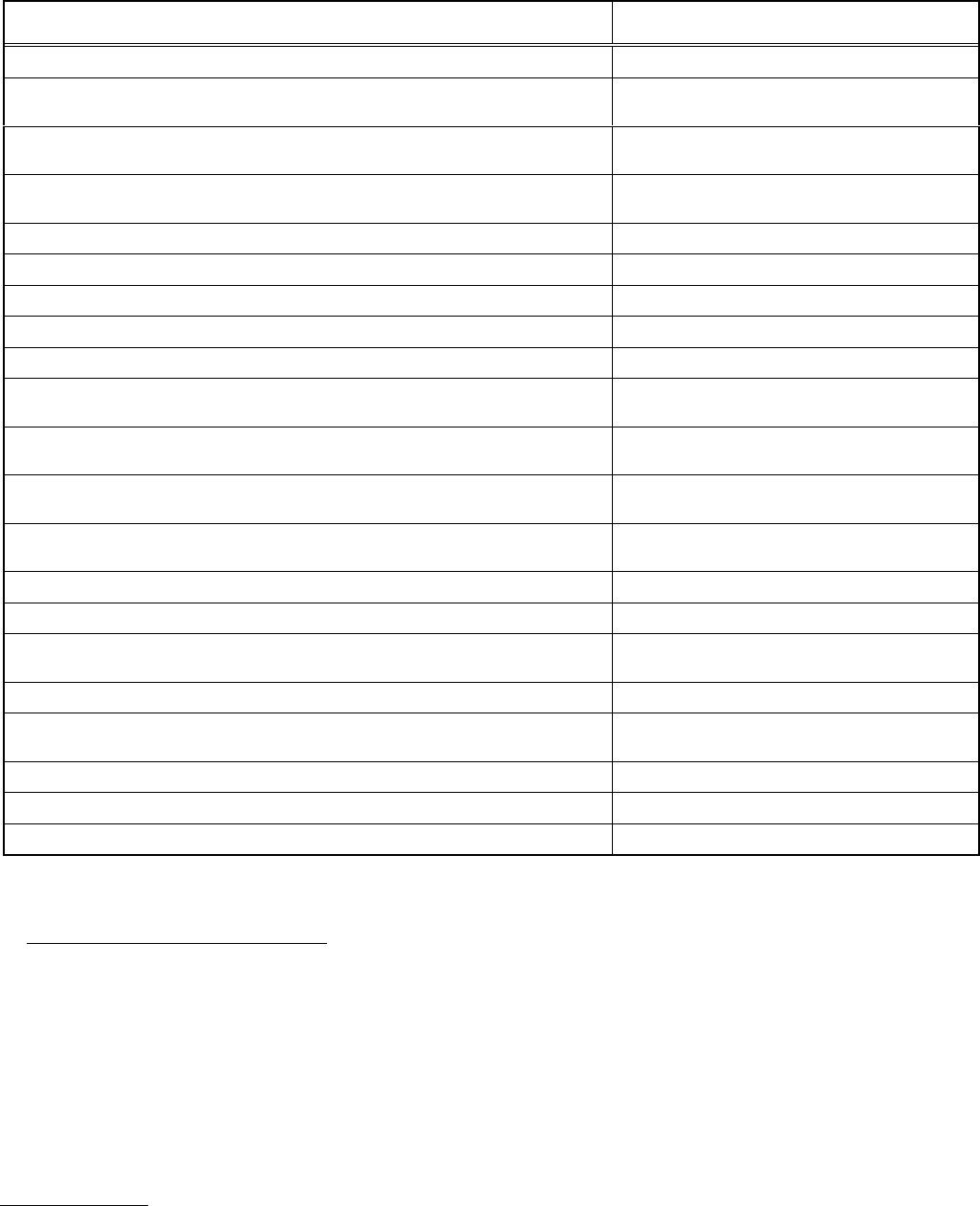

Table 2 describes each of these models, the applications

of the models, and available evidence supporting their

effectiveness. These models of TIC emphasize staff

education, involving consumers, and transforming systems to

be responsive to the needs of trauma survivors. Several

models, including ARC, CARE, and Sanctuary, have an

evidence base (e.g., outcomes-based quantitative research) in

the mental health field (including inpatient and outpatient

settings) and are considered to be promising practices in

trauma-informed care [46]. Others, such as A Long Journey

Home and Phoenix Rising, were developed specifically for

homeless service settings. Most of these models have been

implemented within homeless service settings, and process

and outcome evaluation data are currently being collected.

HOW TRAUMA-INFORMED ARE WE?

ORGANIZATIONAL SELF-ASSESSMENTS

The models described above highlight the need for a

framework that provides the foundation for a paradigm shift

within homelessness service systems. Once a model for TIC

has been identified, an organizational self-assessment can be

utilized as a starting point for systems change.

Self-assessment targets specific areas for change and

indicates how a service delivery model might be adapted to

an organization’s unique needs. As the model is

implemented, a self-assessment is a useful reminder about

important aspects of trauma-informed care that facilitate self-

monitoring and program evaluation. Organizational self-

assessments can also be conducted after implementation of a

paradigm shift in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the

systems change.

Several trauma-informed organizational self-assessments

are currently available or/are in development. They include:

• The Collaboration on Trauma-Surviving Homeless

Children, a partnership between the National Center

on Family Homelessness and the Trauma Center at

Justice Resource Institute (JRI), has developed the

Trauma-Informed Organizational Self-Assessment

for Programs Serving Homeless Families [50] to

help programs assess the degree to which their

services are trauma-informed and to highlight areas

for change. The self-assessment addresses

organizational issues such as delineating program

mission, guidelines, and policies; reviewing services

and policies; establishing a safe and trauma-informed

physical environment; respecting consumer needs and

differences; protecting consumer privacy and

information; encouraging internal and external

community-building; and involving consumers in

program development and evaluation. The instrument

evaluates staff issues, including hiring practices, staff

training and education, and supervision and support.

It also assesses consumer issues, including procedures

for arrival and intake; safety-planning and crisis

prevention; goal setting; and availability of services,

including trauma-specific interventions.

• The Trauma Center at JRI has developed the

Trauma-Informed Facility Assessment [49], a brief

instrument assessing the degree to which an

organization’s physical space is trauma-informed.

This assessment defines several characteristics that

are of primary importance for trauma-informed

organizations, including physical safety, absence of

triggering material, privacy/ confidentiality, and

structure and predictable/consistent response. Other

areas measured by the instrument include

accessibility; organization and hygiene; the ability to

meet the basic needs of consumers and provide links

to resources; the availability of personal/quiet space;

the communication of positive messages; and the

creation of a sense of community, with consumer

ownership of the space and the program.

• Community Connections has developed a Trauma-

Informed Program Self-Assessment Scale and

Planning Protocol [51]. This tool allows

organizations to evaluate the degree to which

program activities and settings are consistent with

five guiding principles: safety, trustworthiness,

choice, collaboration, and empowerment. Six major

domains are evaluated, including: program

procedures and settings; formal services policies;

trauma screening, assessment, and service planning;

administrative support for program-wide trauma-

informed services; staff trauma training and

education; and human-resource practices. Each

domain is evaluated on the basis of review of

program policies, standard program activities, review

of physical space, staff ratings, and consumer ratings.

• As part of a larger study examining integrated

trauma-informed treatment for women with

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 89

Table 2. Models of Trauma-Informed Care

Model Developers Description Key Principles Applications

Research

Evidence

Strengths Limitations

The ARC

Model

(Attachment,

Self-Regulation,

and

Competency): A

Comprehensive

Framework for

Intervention

with Complexly

Traumatized

Youth

Kinniburgh

and

Blaustein [48]

•

•

ARC is a

flexible

framework for

intervention

with

children/famil

ies who have

experienced

complex

trauma. ARC

has been

adapted for

use within

various

milieus.

It has been

applied within

homeless

settings for

runaway and

homeless

youth.

•

•

•

•

10 building blocks,

based on three basic

principles:

Attachment,

Regulation, and

Competency.

Attachment:

Caregiver affect

management,

attunement, consistent

responses, routines

and rituals.

Regulation: Affect

identification,

modulation, and

expression.

Competency:

Executive functions,

self-development &

identity, &

developmental tasks.

Therapeutic

Procedures:

• Psycho-

education;

• Relationship

strengthening;

• Social skills;

• Parent-education

training.

• ARC principles

adapted for use

with homeless

adolescents.

• ARC Agency

Inventory for

homeless/

runaway youth

has been

developed.

• Pilot data:

ARC is

effective in

outpatient

settings.

• Quasi-

experimental

research

studies:

conducted in

outpatient and

milieu settings

in MI, IL, CA,

AL, & MA.

Outcomes:

decreased

trauma

symptoms,

PTSD, and

internalizing/

externalizing

symptoms.

• ARC

concepts-

adapted for

use in

homeless

settings but

not yet been

evaluated.

•

•

•

•

•

Very strong

theoretical basis.

Addresses

developmental

trauma.

Offers a

comprehensive

framework for

milieu change;

provides a model

for trauma-

specific

interventions.

Well-defined,

with an extensive

manual and

comprehensive

training

NCTSN calls it a

"promising

practice"

Collecting

evidence on

effectiveness at

multiple sites.

•

Although

evaluated in

multiple

outpatient

and milieu

settings, it

has yet to

be formally

evaluated in

homeless

settings.

CARE

(Child Adult

Relationship

Enhancement)

Trauma

Treatment

Training

Center

(TTTC).

Revised for

homeless

populations by

NCFH & the

Trauma

Center.

•

•

•

Trauma-

informed

modification

of Parent

Child

Interaction

Therapy

(PCIT).

Skill-based

model for use

in milieu

settings.

Being

modified for

homeless

settings.

CARE guides caregivers

in child-directed and

parent-directed

interactions:

• Caretakers’

competence in

managing child's

problematic

behaviors;

• Caretakers’

competence

reinforcing +

behaviors;

• Reduce parent-child

conflict; and

• Enhance positive

parent-child

interactions.

•

•

•

Trauma

education

component.

Live coaching.

Practice of 3 P

Skills (Praise,

Paraphrase, and

Point-Out

Behavior) to

guide parent-

child

interactions.

•

•

•

CARE is

empirically

informed but

has not yet

been

evaluated.

PCIT, the

foundation

for CARE,

has been

empirically

supported by

numerous

studies.

Piloted in

shelters

•

•

•

Modified PCIT-

Strong

theoretical &

research base

Effective for

building +

caregiver/child

relationships &

building

caregiver

competence.

NCTSN calls it

a promising

practice

•

•

Limited

scope in

terms of

systems

change.

Does not

yet have an

evidence

base within

homelessne

ss.

A Long

Journey Home

Prescott, L.

and NCFH

[44]

A Guide for

Creating

Trauma-

Informed

Services for

Homeless

Mothers and

Children

Offers guidance on:

• Changing the

environment

• Trauma-informed

policies and

procedures

• Trauma-informed

services & support

• Client representation

& staff development

• Training and

supervision

•

Developing

sustainability

• Guide offers

concrete

suggestions for

organizational

shift towards

TIC

• Includes concrete

examples,

exercises, &

suggestions for

staff training.

• In the final

stages of

developme

nt; has not

been

piloted in

homeless

service

settings.

•

•

Practical guide

for making

concrete changes

within systems.

Developed

specifically for

trauma-informed

systems change

within homeless

service settings.

• Still in

developme

nt --does

not yet

have a

research or

practice

evidence

base.

90 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

co-occurring disorders, the W.E.L.L. Project of the

Institute for Health and Recovery (IHR) developed a

toolkit for developing trauma-informed organizations.

This self-assessment tool, entitled Developing

Trauma-informed Organizations: A Toolkit [52],

includes principles of trauma-informed treatment, a

self-assessment for provider organizations, and an

organizational assessment for non-provider

organizations.

Although these self-assessment tools—like the service

delivery models—are still in development and refinement

stages, they reflect advances towards the development of

TIC.

INNOVATIVE PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES

UTILIZING TIC

The development of these models and self-assessment

tools has facilitated the progress of a number of innovative

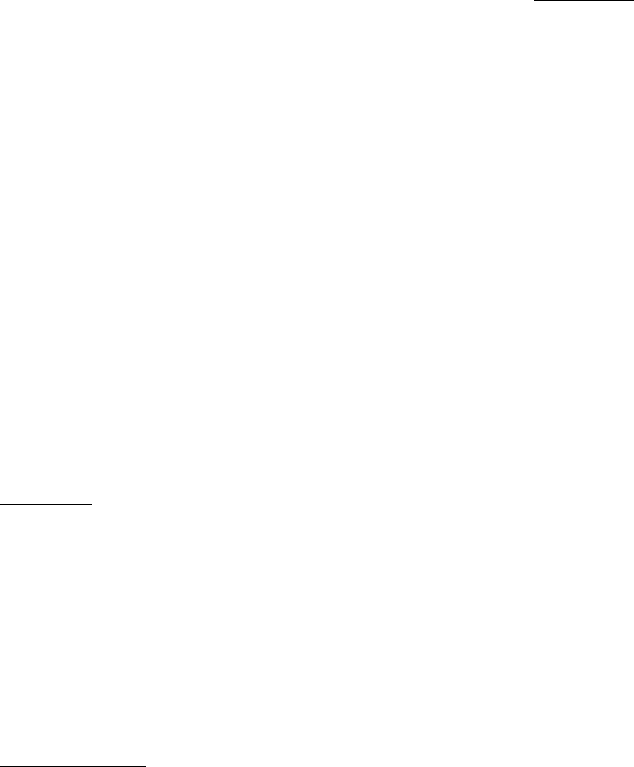

(Table 2) contd…..

Model Developers Description Key Principles Applications

Research

Evidence

Strengths Limitations

Phoenix Rising

Youth on Fire

and the

Trauma

Center at JRI

Phoenix Rising

is an adaptation

of ARC

concepts for use

with homeless

adolescents and

young adults.

Four main components:

• Staff training &

ongoing consultation

• Trauma-informed

milieu changes based

on the Trauma-

Informed Facility

Self-Assessment [49]

• Comprehensive Risk

Counseling and

Services

• Group activities

(expressive art

therapies and

community-building)

Designed for non-

clinical staff in

shelters for

homeless youth.

Offers guidance on:

• Training and

philosophy-shift;

• Self-assessment

• Organizational

and physical

space issues

• Staff issues

• Consumer issues

(skill-building,

development of a

cohesive

environment)

• Being

piloted at a

drop-in

program for

homeless

adolescents

and young

adults in

Cambridge,

MA.

•

•

Practical

guidebook for

concrete

systems

change.

Modification of

a strong

theoretical

model (ARC)

for use at a

drop-in center

for homeless

youth.

•

Manual

under

development

and being

piloted in a

homeless

service

system.

The Sanctuary

Model

Bloom, S. [46]

•

•

Framework

for

intervening

with trauma

survivors and

facilitating

organizational

change.

Originally

developed for

traumatized

adults in

inpatient

units, adapted

for DV

shelters.

• Culture of

nonviolence.

• Emotional

intelligence.

• Inquiry & social

learning.

• Shared governance.

• Open communication.

• Social responsibility.

• Growth and change.

Shared intervention

language: SAGE (Safety,

Affect Management,

Grief, Emancipation) for

adults, SELF (Safety,

Emotions, Loss, Future)

for children.

Concrete tools for

intervention

include:

• Community

meetings

• Red flag reviews

• Psychoeducation

• Self-care

planning

• Safety plans

• Team meetings

• Treatment

planning

conferences

•

•

Program

evaluation

within

inpatient

units:

reduced

PTSD

symptoms

& use of

restraints/

seclusion,

improved

patient

satisfaction,

improved

staff

retention.

Additional

pilot trials

underway.

•

•

•

Theoretical base.

Research

evidence in

multiple settings-

inpatient and

outpatient

NCTSN calls it a

promising

practice

• Although

evaluated

within

multiple

outpatient

and milieu

settings, it

has yet to be

formally

evaluated in

homeless

settings.

Using Trauma

Theory to

Design Service

Systems

Harris and

Fallot [12]

•

Short edited

book

describes

trauma-

informed

systems & the

application of

trauma theory

to systems

change.

Applies

concepts to

various

settings, such

as shelters.

Forms guide

systems

change.

•

•

Systems change

approach.

Self-Assessment and

Planning Protocol

ensures that all levels

of the organization

have an understanding

of trauma, its

sequelae, and the

impact of trauma in

shaping a consumer’s

responses.

•

•

•

•

Book describing

the model:

Using Trauma

Theory to

Design Service

Systems

Trauma-

Informed Self-

Assessment and

Planning

Protocol.

Trauma-

Informed Self-

Assessment

Scale

Implementation

Form.

•

•

Piloted in

DC, ME, &

CT. Most

pilot projects

within

mental health

& substance

abuse

settings.

Initial pilot

project data:

support for

this model

from

organizations

, staff, and

consumers.

•

•

•

Theoretical

base.

Self-

Assessment and

Planning

protocol offers

concrete steps

for

intervention.

Training and

consultation is

available.

•

•

Evidence

base comes

from

unpublished

pilot studies.

Not yet

evidence on

this model

in homeless

service

settings.

Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 91

programs that are working to build TIC within homelessness

service systems. We selected various programs that illustrate

lessons from the field with diverse populations experiencing

homelessness.

Trauma-Informed Family Shelters

• The Collaboration on Trauma-Surviving Homeless

Children—a partnership among the National Center

on Family Homelessness, the Trauma Center at

Justice Resource Institute, and other agencies—has

worked with various shelters within the Boston

metropolitan area to build trauma-informed homeless

services. Experts in trauma and homelessness worked

jointly to develop trauma-based training and

consultation targeted specifically to the needs of

homeless families. Trauma training was offered to all

levels of program staff, from administrators to clinical

case managers to family advocates. Staff participated

in regular trauma team meetings that focused on both

trauma-informed organizational change and trauma-

focused case consultation. Trauma-informed

programming was also instituted within shelter

settings. This included community-building activities,

an expressive music program, and self-care activities

for residents. The goal of this program was to

increase the staff’s knowledge of traumatic stress,

their skill level in responding to trauma-related issues,

their self-efficacy about working with individuals and

families who have been traumatized, and their

awareness of issues related to vicarious trauma and

burnout, and self-care. Initial evaluation results

indicated positive outcomes, with high levels of

support for the organizational shift to trauma-

informed programming, increased staff confidence,

fewer resident conflicts, better relationships among

staff and residents, and fewer resident terminations.

Trauma-Informed Domestic Violence Shelters

• The Domes

tic Violence (DV) and Mental Health

Policy Initiative in Chicago is working with the

Department of Public Health, the Mayors Office, and

several domestic violence shelters to create three

“Centers of Excellence” for trauma and domestic

violence. This pilot program will evaluate changes

among organizations, providers, and survivors. The

initiative is also developing a DV-Trauma Core

Curriculum to assist providers in offering more

trauma-informed services within domestic violence

programs.

Trauma-Informed Homeless Outreach Programs

• The Women’s Violence Prevention Project Alliance at

the Friends of the Shattuck shelter in Boston is an

outreach program for homeless men and women that

is working towards becoming more trauma-informed.

This program developed a manual to help providers

and outreach workers build their understanding of

trauma and learn how to respond appropriately to

survivors. The manual also includes a safety-planning

guide for use with individuals who are living on the

streets.

Trauma-Informed Programs for Homeless Youth

• Youth on Fire is a drop-in center for homeless

adolescents and young adults in Cambridge,

Massachusetts. This program utilizes the Phoenix

Rising model, an adaptation of ARC (Attachment,

Self-regulation, and Competency model) for homeless

and at-risk youth. Program staff members have

received trauma training and continue to receive

trauma consultation from the Trauma Center at

Justice Resource Institute. They are working to

modify their environment to become more trauma-

informed. This program also offers trauma-specific

group interventions.

• The Community Trauma Treatment for Runaway and

Homeless Youth is a partnership among several

agencies in the Los Angeles area that provides

outreach and services to homeless youth. This

program has utilized the ARC model to institute a

philosophical shift towards becoming trauma-

informed. They developed an ARC-based

organizational self-assessment in order to target areas

for change within participating agencies. They have

also instituted trauma-informed case conference

meetings in which ARC concepts are used for case

review. Trauma-specific interventions have also been

instituted within this program.

• The Homeless Children’s Network is a consortium of

fifteen homeless and domestic violence programs in

San Francisco, California. This program provides

therapy and case management to homeless children

and their families. Their theoretical framework

considers homelessness to be a traumatic stressor for

children.

Trauma-Informed Treatment Programs for Homeless

People with Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance

Use Problems

• The Seeking Treatment and Recovery (STAR)

Program in Florida provides treatment for homeless

people who are suffering from co-occurring mental

illness and substance abuse. After determining that

79.5% of the homeless individuals served by their

program acknowledged a history of physical or sexual

abuse, this program began to make changes to

become more trauma-informed. The program

instituted a formal process of screening for trauma

exposure. Based on the high level of trauma exposure

reported by men, they expanded the trauma-specific

services to include treatment for male survivors. The

program also incorporated various training activities

to raise trauma awareness and to build trauma-

informed services [28].

Programs Utilizing a Trauma Framework for Veterans

• Mary E. Walker House is a transitional-living

program for homeless women veterans in Coatesville,

Pennsylvania, that focuses on recovery from trauma

and substance abuse. This program includes a trauma

framework and also offers trauma-specific services.

92 The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 2010, Volume 3 Hopper et al.

• The Renew program is a V.A. program in Long

Beach, California, which serves both homeless and

non-homeless women veterans who have experienced

military sexual trauma, and often pre-military sexual

trauma.

• New Directions is a V.A. program in Los Angeles,

California, that offers substance abuse and mental

health treatment utilizing a trauma framework. Its

Women’s Program offers trauma counseling, with

100% of clients reporting abuse. The Executive

Director noted, “Most of our clients have experienced

multiple traumas, including physical trauma as a

child, military trauma and years of abuse on the

streets and in prisons. Since veterans are known to

have a higher degree of trauma than the general

public, it would be most cost effective to begin to

treat trauma as the core disability rather than separate

and apart from all other symptoms” [53].

These program examples illustrate the beginning of a

paradigm shift in which homeless services sites are

recognizing the central role of trauma in the lives of

consumers. These programs are being implemented in

diverse settings including family-based shelters, domestic

violence programs, outreach programs, dual diagnosis

programs for homeless individuals, and programs for

homeless youth and veterans. However, this shift is only

beginning. Many programs do not yet recognize the central

role of trauma. Guidance from state and federal initiatives is

likely to facilitate broader awareness of the need for TIC

within behavioral health systems and, more specifically,

within homelessness services settings.

SELECTED STATE AND FEDERAL INITIATIVES TO

ESTABLISH TIC

Over the past ten years, various state and federal policies

have focused on the importance of establishing trauma-

informed services within mental health and substance abuse

settings. In 1998, the National Association of State Mental

Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) issued a position

statement on services and supports for trauma survivors,

recognizing that “the psychological effects of violence and

trauma in our society are pervasive, highly disabling, yet

largely ignored.” The statement articulated a commitment to

address the issue of trauma. The report, Models for

Developing Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Systems

and Trauma-Specific Services, defined “trauma-informed”

and described programs that have implemented trauma-

informed models on a statewide or local level [54].

NASMHPD also developed a Trauma Services

Implementation Toolkit for State Mental Health Agencies

[42] that describes products being used by various state

agencies to work towards building trauma-informed systems.

Although these policy documents are not directed towards

homeless service systems, they provided momentum in the

social-services fields towards incorporating knowledge of

trauma into service systems.

Regional and national initiatives regarding the need for

TIC within the homelessness field are even more recent.

Within the past ten years, a number of homeless service

organizations and coalitions have begun to emphasize the

importance of addressing the impact of trauma among

individuals experiencing homelessness, and several training

and technical assistance centers have emerged that are

actively promoting trauma-informed homelessness services.

The Homelessness Resource Center (HRC), a

SAMHSA-funded program, provides resources, training, and

technical assistance on issues affecting people who are

homeless. Its mission is to improve the lives of people who

are homeless and have been impacted by trauma, substance

abuse, and mental health issues. One of HRC’s guiding

principles is to foster trauma-informed recovery systems.

Through its website, the HRC disseminates tips, tools, and

knowledge-based products that can be used by programs

interested in implementing trauma-informed care. See

www.homeless.samhsa.gov.

The National Center for Trauma-Informed Care,

funded by SAMHSA’s Center for Mental Health Services

(CMHS), offers educational materials, technical assistance,

and training to social services systems to build an

understanding of the impact of trauma and effective trauma-

based interventions. In collaboration with the Homelessness

Resource Center, the National Center for Trauma-Informed

Care offers trauma-informed training to providers in the Gulf

Coast recovery area. In addition, training in trauma-informed

care has been offered to Projects for Assistance in Transition

from Homelessness (PATH) programs.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

(NCTSN), another SAMHSA-supported program, has

focused on the impact of traumatic stress in the lives of

children. The Network has been active in promoting trauma-

informed care, including trauma awareness within homeless

service settings for youth. The Homelessness and Extreme

Poverty Working Group is a branch of NCTSN that devotes

itself to the intersection of trauma, poverty, and

homelessness in children.

The Department of Veterans Affairs offers specialized

services to homeless veterans, and is increasingly addressing

sexual trauma among female veterans. However, the

National Coalition for Homeless Veterans noted that “with

greater numbers of women in combat operations, along with

increased identification of and a greater emphasis on care for

victims of sexual assault and trauma, new and more

comprehensive services are needed.” The Coalition’s 2007

public policy priorities include increasing homeless veterans’